دوشنبه

دوشـنـبـه

Дюшамбе (ديوشامبى، 1924–29), Сталинабад (ستالينآباد، 1929–60) | |

|---|---|

عاصمة طاجيكستان | |

| الإحداثيات: 38°32′12″N 68°46′48″E / 38.53667°N 68.78000°E | |

| البلد | |

| المنطقة | Dushanbe |

| الأحياء | قائمة

|

| الحكومة | |

| • العمدة | رستم إمامعلي (حزب الشعب الديمقراطي (طاجيكستان)) |

| المساحة | |

| • عاصمة طاجيكستان | 100 كم² (40 ميل²) |

| • الحضر | 185 كم² (71 ميل²) |

| المنسوب | 706 m (2٬316 ft) |

| التعداد (2008)[1] | |

| • عاصمة طاجيكستان | 679٬400 |

| منطقة التوقيت | UTC+5 (GMT) |

| • الصيف (التوقيت الصيفي) | UTC+5 (GMT) |

| مفتاح الهاتف | 372[2] |

| لوحة السيارة | 01, 05[3] |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | www.dushanbe.tj |

دوشنبه (بالطاجيكية: Душанбе حتى 1929, ستالين أباد حتى 1961, هي عاصمة طاجيكستان وأكبر مدنها, يصل عدد سكانها إلى 679.400 طبقا لتقديرات 2008. وتعني كلمة دوشنبه "الإثنين" في الطاجيكية,[4] وذلك يعكس نشأة المدينة من قرية كانت في الأصل مقراً لسوق يعقد يوم الإثنين.

تُعَدُّ هذه المدينة مركزًا صناعيًا مهماً، ومركزًا لوسائل النقل والمواصلات، ومركزًا للعلوم والثقافة. وتشمل منتجاتها، الحرير، والمنسوجات والآلات.

اندمجت ثلاث قرى صغيرة في عام 1926، وكونت مدينة دوشانبي. غيَّرت الحكومة في عام 1929 اسم المدينة وأطلقت عليها اسم ستالين أباد تكريمًا لشخص يوسف ستالين. وفي إطار الحملة المعادية لفكر ستالين عام 1961، أُطلق على المدينة مرة أخرى دوشانبه. تفكك الاتحاد السوفيتي عام 1991، وأصبحت جمهورية طاجكستان دولة مستقلة.

تم اختيارها كعاصمة لدولة طاجيكستان في بداية عام 1924م تقع في وسط وادي حسار ، وتحيط بها الجبال من جهاتها الأربعة ( الجبال تمثل 93% من مساحة طاجكيستان ) . لها إدارة حكومية خاصة ، ويديرها برلمان ، ولها أربع نواحي إدارية وهي : ( ناحية إسماعيل ساماني – ناحية ابن سينا – ناحية فردوسي – ناحية شاه منصور ).

كما تضم المؤسسات التعليمية العليا ، والتي من أهمها أكاديمية العلوم التاجيكية ، وأكاديمية العلوم التربوية ، وجامعة تاجيكستان القومية ، وجامعة الطبّ ، ومعهد المعلمين ، وغيرها ، ويبلغ عدد الجامعات فيها أكثر من عشر جامعات ، كما يوجد فيها أكثر من مائة مدرسة ابتدائية وثانوية ، بالإضافة لأكثر من ألف روضة للأطفال . يوجد فيها كثير من الأماكن التاريخية ، والتي من أهمها المتحف القومي ، والمتحف التاريخي القديم ،ومكتبة فردوسي ، معهد الآثار الخطية القديمة . كما فيها أجمل الحدائق والمنتزهات العامة كالحديقة المركزية ، وحديقة النصر المشهورة بروعة جمالها ، والتي منها يستطيع الإنسان أن يرى كل دوشنبه من أعلى ؛ لأنها تقع على تل مرتفع . كما تضم أربع ملاعب كبيرة لكرة القدم ، والتي تقام فيها الدورات المحلية والإقليمية والدولية .

تعتبر أكبر مركز علمي وثقافي ، حيث تضم كل من أكاديمية العلوم التاجيكية ، وأغلب الجامعات العليا . – تعتبر دوشنبه اليوم مدينة للسلام والصداقة والأخوة . – لقد اختارتها منظمة اليونسكو التابعة للأمم المتحدة لتكون مدينة السلام في منطقة آسيا والمحيط الهادي ، فكرمتها وحصلت على الجائزة الأولى من اليونسكو .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

التاريخ

الأزمنة القديمة

في العصر الحجري، Mousterian tool-users inhabited the Gissar Valley near modern-day Dushanbe.[5] The Gissar culture, whose stone tools were discovered within modern-day Dushanbe at the confluence of the Varzob and Luchob,[6] Bishkent culture, and Vakhsh culture all were thought to have inhabited the valley in the second millennium BC, during the Neolithic period, and were primarily involved in cattle breeding, agriculture, and weaving.[7][8][9]

Near the Dushanbe International Airport, Bronze Age burials were discovered dating from the end of the second to the beginning of the first millennium BC.[10] Achaemenid dishes and ceramics were found 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) east of Dushanbe in Qiblai,[11] as the city was controlled by the Achaemenids from the 6th century BC.[9] Archaeological remnants of a small citadel dating to the 5th century BC have been discovered 40 kilometres (25 mi) south[12] and wedge-shaped copper axes have been discovered from the 2nd century BC.[13]

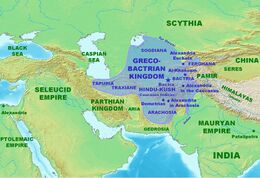

The Seleucids conquered the region in 312 BC.[14] A small Greco-Bactrian settlement of about 40 hectares was dated to the end of the 3rd century BC.[13][15][16] The oldest coin found in the city is a Greco-Bactrian coin depicting Eucratides (r. 171–145 BC) and another was found depicting Dionysus.[14][17] There was also a Kushan city on the left bank of the Varzob river from the 2nd century BC to 3rd century AD containing burial sites from the time period.[13][16][18] The Kushans created other settlements such as Garavkala, Tepai Shah, Shakhrinau, and Uzbekontepa.[19][20] The Sasanian Empire invaded Sogdiana in the 5th century, possibly giving coins as tribute to the Kidarites which ended up on the site of today's city.[21][22]

The ruins of a Buddhist monastery of the Hephalite period of the late 5-6th century, now referred to as Ajina Tepe, lie in the Vaksh valley near Dushanbe.[23] Other settlements from the Tokharistan period have also been discovered, like the town of Shishikona that was destroyed during the Soviet era and depopulated during the Mongol invasion.[24][25] International trade picked up during this period in the region.[26] A castle was also discovered dating from the time period.[27] In 582, the Western Turkic Khaganate gained control over the region.[14] In the 7th century, a Chinese pilgrim visited the region and mentioned the city of Shuman, possibly on the site of modern Dushanbe.[28][29]

After the Arab conquest, the Samanids controlled the region, which was involved in crafts and trade,[9] and in the 10th-12th centuries the medieval city of Hulbuk developed near Dushanbe, which notably contained the palace of the governor of Khulbuk, "an artistic treasure of the Tajik people", among other smaller medieval settlements like Shishikhona.[30] The Kharakhanids minted coins from 1018 to 1019 found in the city.[31] The city came under the influence of the Ghurids from the 12th to 13th centuries.[9]

Other smaller settlements were founded during the Late Middle Ages after the Mongol invasion, such as Abdullaevsky and Shainak. Timur conquered the region during this time period and various other empires controlled the city. The city's economy started to rely more heavily on crafts and trade.[9][32][14]

بلدة سوق

The first time Dushanbe appeared in the historical record was in 1676, in a letter sent from the Balkh khan Subhonquli Bahodur to Fyodor III, the Tsar of Russia. However, the Balkh historian Mahmud ibn Wali mentioned the area in the 1630s in the book Sea of Secrets Regarding the Values of the Noble.[33][34][35] At first, the town was called "Kasabai Dushanbe", when it was under the control of Balkh. This name reflected both Dushanbe's status as a town, with Kasabai meaning town, and the influence of trade, as the name Dushanbe, which means Monday in Persian, was due to the large bazaar in the village that operated on Mondays. Dushanbe's location between the caravan routes heading east–west from the Gissar Valley through Karategin to the Alay Valley, and north–south to the Kafirnigan River and then to Vaksh Valley and Afghanistan through the Anzob Pass from the Fergana and Zeravshan valleys that ultimately led traders to Bukhara, Samarkand, the Pamirs, and Afghanistan incentivized the development of its market.[13][36][37] At the time, the town had a population of around 7,000–8,000 with around 500–600 households.[38]

By 1826, the town was called Dushanbe Qurghan (بالطاجيكية: Душанбе Қурғон, Dushanbe Qurghon, with the suffix qurƣon from Turkic qurğan, meaning "fortress"). It was first Russified as Dyushambe (Дюшамбе) in 1875. It had a caravanserai, a stopping point for travelers to Samarkand, Khujand, Kulob and the Pamirs. It boasted 14 mosques with maktabs, 2 madrassas, and 14 teahouses at the turn of the 19th century. At that time, the town was a citadel on a steep bank on the left bank of the Varzob River with 10,000 residents.[9][39][38] It was a center for weaving, tanning, and iron smelting production in the region. Various states, including Hisor, exercised control over the city during the 18th and early 19th century despite Bukharan claims of sovereignty. In 1868, the Tsarist government established suzerainty over Bukhara. In the unstable environment of Russian intervention and local revolts, Bukhara took over the Dushanbe region, control over which the Emirate was able to sustain through the gradual establishment of a Russian-influenced centralized state.[40][41] The first hospital in the village was constructed in 1915 by Russian investment[42] and an early railroad was proposed to connect the market town with the Russian railway system in 1909, but was abandoned after a review determined the venture would not be profitable, although the town did have a functioning railroad to Kagan.[43]

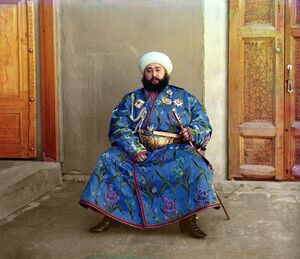

In 1920, the last Emir of Bukhara briefly took refuge in Dushanbe after being overthrown by the Bolshevik revolution. After the Red Army conquered the area the next year, he fled to Afghanistan on 4 March 1921.[44][45][46] In February 1922, the town was taken by Basmachi troops led by Enver Pasha after a siege,[44] but on 14 July 1922 again came under the power of the Bolsheviks[47][48] soon before the death of Enver Pasha on 4 August 1922 outside of Dushanbe.[44][49] It was a part of the Bukharan PSR until the formation of the Tajik ASSR.[50]

عاصمة جمهورية طاجيكستان ا.س.ذ.

Dushanbe was proclaimed the capital of the جمهورية طاجيكستان الاشتراكية السوڤيتية الذاتية as a part of the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic in October 1924, and the government started to function formally on 15 March 1925.[51][52][53]

Dushanbe was chosen instead of larger-populated villages in Tajikistan because of its role as a crossroads of Tajikistan for its large market served as a meeting place for much of Tajikistan's population. Along with its market, there was a lively livestock trade as well as trade in fabrics, leather, tin products, and weapons.[54] The mild Mediterranean climate was another reason Soviet authorities chose the city as the capital.[43]

Before the Emir's relocation to the city, Dushanbe had the only Jewish population in Eastern Bukhara (of about 600) whom were involved in trade and tailoring. When the Emir moved to the city in 1920, however, the Jewish population's property was plundered and the Jews were relocated to Hisor. They were only let back into Dushanbe with its conquest by the Red Army, and in the 1920s and 1930s their population gradually increased with Bukharan immigrants.[55][43] Dushanbe was also officially recognized as the capital of the Emirate of Bukhara during its waning days as it served as the last refuge of the last Emir of Bukhara during its conquest by the Soviet Union, possibly another motivating factor for the decision to establish the new ASSR's capital in the village.[54] The population during Soviet conquest and Basmachi revolts declined from an already meager 3,140 in 1920 to only 283 in 1924 with only 40 houses still standing.[51][43][56] To aid in the recovery, the Soviet authorities temporarily exempted much of the population from having to pay taxes. In 1923, the Soviets created Dushanbe's first telegraph link to Bukhara, initiated its first railroad to Termez,[51] and set up a telephone switchboard in 1924.[57] On 12 August 1924, the first newspaper of the town, Voice of the East (Russian: Овози Шарк), was published in Arabic and soon after a Russian-language paper, Red Tajikistan (Russian: Красный Таджикистан), began publication. Power plants and electricity were introduced to Dushanbe during this time. By the end of 1924, the first regular plane routes from Dushanbe came into operation, with one connection to Bukhara and later one to Tashkent. The post office was also set up that year.[43] Construction on the railroad commenced on 24 June 1926, and it was completed in November 1929, connecting Dushanbe with the Trans-Caspian railroad and kickstarting economic growth.[34] In 1925, the first boy's boarding school was constructed in the capital.[43] On 1 September 1927, the first pedagogical college opened in Dushanbe and in November the motor road from Dushanbe to Kulob was completed.[53] Tajiks from the countryside were given assistance and free land plots in the capital to increase its population and development.[43]

عاصمة جمهورية طاجيكستان ا.س.

جمهورية طاجيكستان الاشتراكية السوڤيتية، التي كانت في السابق طاجيكستان ج.ا.س.ذ.، انفصلت عن جمهورية أوزبكستان الاشتراكية السوڤيتية في 1929، وعاصمتها ديوشامبه Dyushambe تغير اسمها إلى ستالينآباد (بالروسية: Сталинабад؛ بالطاجيكية: Сталинобод Stalinobod) على اسم يوسف ستالين في 19 أكتوبر 1929، لتضم القرى المجاورة شاه منصور، مولانا، و ساري آسيا.[34][58][53]

In the years that followed, the city developed at a rapid pace.[13] The Soviets transformed the area into a center for cotton and silk production, and tens of thousands of people relocated to the city. The population also increased with thousands of ethnic Tajiks migrating to Tajikistan from Uzbekistan following the transfer of Bukhara and Samarkand to the Uzbek SSR as part of national delimitation in Central Asia.[49] Industry during the time period was limited, focused on local production, although it had expanded by nine times since 1913 by 1940.[51][46] The first bus line began operating in 1930 and in 1938, Komsomol members constructed Komsomolskoye Lake in the city.[43][59]

Many of these projects occurred under the 1925–1932 mayoralty of Abdukarim Rozykov, one of the first mayors of Dushanbe, who sought to transform it into a "model communist city" through modernization and urban planning. Mikhail Kalitin continued the industrial development of Dushanbe, building the Komsomolskoye Lake and promoting industry in the city.[60] Towards the end of this period, in the late 1930s, there were 4,295 buildings in Dushanbe.[61]

During World War 2, the population of Dushanbe and Tajikistan swelled with 100,000 evacuees from the Eastern Front that led to the deployment of 17 hospitals in the city.[54] The city's industry also greatly increased during the war, as the Soviets wanted to move critical infrastructure far behind enemy lines, and industries like textile manufacturing and food processing grew.[51] In 1954, there were 30 schools in the city; a medical institute named after Avicenna; the Stalinabad Academy of Sciences; the University of Stalinabad, which was founded in 1947 and had 1,500 students;[62] and the Stalinabad Pedagogical Institute for Woman, established on 1 September 1953.[63] In 1960, gas supply reached the capital through a gas pipeline opened from Kyzyl to Tumxuk to Dushanbe. On 10 November 1961, as part of de-Stalinization, Stalinabad was renamed back to Dushanbe, the name it retains to this day.[64] In 1960, under the leadership of Mahmudbek Narzibekov, the first zoo was built in the city. Later in the decade the mayor developed a plan to end the housing shortage and provide free apartments.[60]

The Nurek Dam, which would have been the tallest dam in the world, was completed 90 kilometres (56 mi) south east of Dushanbe during the 1960s. The Rogun Dam, upstream from Nurek Dam, was started in that period as well. They were both megaprojects meant to showcase Soviet innovation and development in Tajikistan. However, while the Nurek Dam was completed, the Rogun Dam was cancelled in the 1970s because of stagnating Soviet economic growth.[65][66] On 2 August 1979, the population of Dushanbe reached 500,000,[53] and it had the highest population growth rate in the Soviet Union.[67]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الشغب والاضطرابات

In the 1980s, environmental problems and crime began to increase. Mass violence, hooliganism, binge drinking, and violent assaults became more common. There was an attack on foreign students at the Agricultural Institute in 1987 and a riot in the Pedagogical Institute two years later. Increasing regionalism also destabilized the SSR.[68]

On 10–11 February 1990, 300 demonstrators gathered at the Communist Party Central Committee building after it was rumored that the Soviet government planned to relocate tens of thousands of Armenian refugees to Tajikistan. In reality, only 29 Armenians went to Dushanbe and were housed by their family members. However, the crowd kept growing in size to 3-5 thousand people; soon after, violence broke out. Martial law was quickly declared and troops were sent in to protect ethnic minorities and defend against vandalism and looting. The number of people protesting increased significantly, however, and they attacked the Central Committee building. The 29 Armenians were quickly evacuated on an emergency flight after shots were fired.[69]

A few days after, and with looting still occurring throughout the city, demonstrators created the Provisional People's Committee, or the Temporary Committee for Crisis Resolution, which put forward demands such as "the expulsion of Armenian refugees, the resignation of the government and the removal of the Communist Party, the closure of an aluminum smelter in western Tajikistan for environmental reasons, equitable distribution of profits from cotton production, and the release of 25 protesters taken into custody."[69]

Many high-ranking officials resigned and the protector's goal of toppling the government was almost successful, but Soviet troops moved into the city, declared the demands illegal, and rejected the resignation of the high-ranking officials. 16-25 people were killed in the violence; many if not most were Russian.[69]

The riots were largely fueled by concerns about housing shortages for the Tajik population, but they coincided with a wave of nationalist unrest that swept Transcaucasia and other Central Asian states during the twilight of Mikhail Gorbachev's rule.[70]

After the increase of organized opposition from the Democratic Party of Tajikistan and Rastokhez, glasnost by Gorbachev, economic contraction, and increased opposition by regional elites, Qahhor Mahkamov disbanded the Communist Party of Tajikistan on 27 August 1991 and quit the party the next day. On 9 September 1991, Tajikistan's government declared independence from the Soviet Union.[71]

عاصمة طاجيكستان

Dushanbe became the capital of an independent Tajikistan on 9 September 1991.[71] Iran, the United States, and Russia soon opened embassies in Dushanbe in early 1992.[53]

Dushanbe was controlled by the Popular Front-supported government during most of the 1992–1997 Tajikistani Civil War, although the Islamist and Democratic United Tajik Opposition managed to capture the capital in 1992 until 8000 Russian-backed and Uzbekistani-backed government troops regained control of Dushanbe.[72] Most of the Russian population fled the capital during the violence of this time period while large amounts of rural Tajiks moved in; by 1993, more than half of the Russian population had fled.[34][73] The factions during the civil war were organized primarily upon regional lines.[72] The war was ended by a 27 June 1997 armistice, administered by the UN, that guaranteed the opposition 30% of the positions in the government.[74]

In 2000, Dushanbe received internet access for the first time.[53] In 2004, the UNESCO declared Dushanbe as a city of peace.[75] Mahmadsaid Ubaidulloev was declared mayor of Dushanbe in 1996, after during the civil war era many said he was in real control of the government.[76] He was the mayor of the capital for the longest term of any mayor, 21 years, until 2017.[60] From independence, the city's economy has grown consistently up until the COVID-19 recession.[77][78] In January 2017, Rustam Emomali, current President Emomali Rahmon's son, was appointed Mayor of Dushanbe, a move which is seen by some analysts as a step to reaching the top of the government.[79]

الجغرافيا

Dushanbe is situated at the confluence of two rivers, the Varzob (flowing from north to south) and the Kofarnihon. It is 750 metres (2,460 ft)–930 metres (3,050 ft) above sea level; in the south and west, the elevation is closer to 750 metres (2,460 ft)–800 metres (2,600 ft), while in the north and northeast it reaches 900 metres (3,000 ft)–950 metres (3,120 ft). The north and east of the city is bounded by the Gissar range, which can reach up to 4,000 metres (13,000 ft) above sea level, and is bounded on the south by the Babatag, Aktau, Rangontau and Karatau mountains which reach a height from 1,400 metres (4,600 ft)–1,700 metres (5,600 ft) above sea level; Dushanbe, therefore, is an intermontane basin located in the Gissar Valley.[13][80] It has a primarily hilly terrain. 80% of Dushanbe's buildings are located within the valley, which has a width of approximately 18 kilometres (11 mi)–100 kilometres (62 mi).[81][82] Before the 1960s, most of Dushanbe was located on the left bank of the Varzob river, but increased construction led to the city expanding across it.[80]

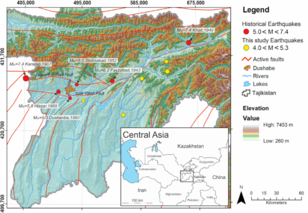

Dushanbe is located in an area with high seismicity. The magnitude of potential earthquakes is thought to reach a maximum of 7.5-8. Over the past 100 years, many earthquakes from a 5-6 magnitude have been felt in the city, such as the 1949 Khait earthquake.[80][83]

الطقس

| بيانات مناخ Dushanbe (1991–2020, extremes 1926–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| الشهر | يناير | فبراير | مارس | أبريل | مايو | يونيو | يوليو | أغسطس | سبتمبر | اكتوبر | نوفمبر | ديسمبر | العام |

| العظمى القياسية °س (°ف) | 21.8 (71.2) |

27.7 (81.9) |

32.2 (90) |

35.3 (95.5) |

38.8 (101.8) |

44.1 (111.4) |

43.7 (110.7) |

45.0 (113) |

38.9 (102) |

36.8 (98.2) |

31.9 (89.4) |

24.3 (75.7) |

45٫0 (113) |

| العظمى المتوسطة °س (°ف) | 9.0 (48.2) |

11.0 (51.8) |

17.0 (62.6) |

22.8 (73) |

27.9 (82.2) |

33.6 (92.5) |

36.4 (97.5) |

35.5 (95.9) |

31.3 (88.3) |

24.4 (75.9) |

16.7 (62.1) |

11.1 (52) |

23٫1 (73٫6) |

| المتوسط اليومي °س (°ف) | 3.1 (37.6) |

5.0 (41) |

10.5 (50.9) |

15.8 (60.4) |

20.1 (68.2) |

25.1 (77.2) |

27.4 (81.3) |

26.0 (78.8) |

21.2 (70.2) |

14.7 (58.5) |

9.0 (48.2) |

4.6 (40.3) |

15٫2 (59٫4) |

| الصغرى المتوسطة °س (°ف) | -0.9 (30.4) |

0.5 (32.9) |

5.5 (41.9) |

10.1 (50.2) |

13.4 (56.1) |

17.2 (63) |

18.9 (66) |

17.2 (63) |

12.7 (54.9) |

7.8 (46) |

3.8 (38.8) |

0.4 (32.7) |

8٫9 (48) |

| الصغرى القياسية °س (°ف) | −26.6 (-15.9) |

−17.6 (0.3) |

−12.9 (8.8) |

-6.1 (21) |

1.2 (34.2) |

8.4 (47.1) |

10.9 (51.6) |

8.2 (46.8) |

-1.0 (30.2) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

−13.5 (7.7) |

−19.5 (-3.1) |

−26٫6 (−15٫9) |

| هطول mm (inches) | 100 (3.94) |

95 (3.74) |

102 (4.02) |

112 (4.41) |

75 (2.95) |

17 (0.67) |

4 (0.16) |

1 (0.04) |

4 (0.16) |

29 (1.14) |

55 (2.17) |

60 (2.36) |

654 (25٫75) |

| % Humidity | 69 | 67 | 65 | 63 | 57 | 42 | 41 | 44 | 44 | 56 | 63 | 69 | 57 |

| Avg. precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 8.5 | 9.1 | 13.4 | 9.8 | 7.8 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 3.7 | 5.3 | 8.1 | 68٫8 |

| Sunshine hours | 120 | 121 | 156 | 198 | 281 | 337 | 352 | 338 | 289 | 224 | 164 | 119 | 2٬699 |

| Source #1: Pogoda.ru.net[84] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Deutscher Wetterdienst (humidity 1951–1993 and precipitation days 1961–1990)[85] NOAA (sun, 1961–1990)[86] | |||||||||||||

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Flora and fauna

Before the 20th century, the city had some vegetation such as bushes of Bukhara almonds, but the creation of the city mostly removed natural vegetation. The green belt, however, and the botanical garden introduced new vegetation to the city. The city has over 150 species of trees and shrubs, with only about 15 native to the city[80] and 22% of the city being occupied by green space.[87]

There are 14 identified species of mammals in urban Dushanbe, including a fox, a weasel, the marbled polecat, the long-eared hedgehog, five bats, and five rodents. There are 130 identified bird species in the city, such as rock pigeons, blue pigeons, and turtle doves. Migratory birds are common, often staying only in fall and summer. There are 47 identified reptiles in Dushanbe, such as geckos, snakes, lizards, and turtles. Amphibians, like the marsh frog and the green toad, live in the cleaner water bodies of the city. The 14 identified fish species of Dushanbe live in the rivers, lakes, and ponds of the city. Some species are the marinka, the Tajik char, and the Turkestan catfish in the Varzob rivers, along with 7 in the Kofarnikhon, and species like carp, goldfish, striped swine, and mosquito fish in the lakes and ponds. 300 identified species of insects inhabit the city, mostly cicadas, psyllids, aphids, scale insects, bugs, beetles, and butterflies. The endemic Hissar grape hawk moth lives in the city as well, and malaria-carrying insects have been increasing in the city. Phytonematodes are a menace to plants in the city, with 55 distinct identified species, the most damaging of which are the root gall nematodes. Rare or endangered species include the radiant tachysphex, the white-bellied arrow eagle, and the European free-tailed bat.[80]

الأحياء

تنقسم دوشنبه إلى الأحياء التالية:

Dark Green: Shah Mansur

Purple: Ismail Samani

Light Green: Avicenna

Yellow: Ferdowsi

Dushanbe is divided into the following districts:

| District name | Former name | Area, | Population,

persons (as of previous 2019 borders)[88] |

District Chairman[90] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ismail Samani (بالطاجيكية: Исмоили Сомонӣ, Ismoili Somoni; فارسية: اسماعیل سامانی) | October (Октябрьский) | 37.6 | 148,700 | Sami Sharif Hamid |

| Avicenna (Sino) (بالطاجيكية: Абӯалӣ Ибни Сино, Abūali Ibni Sino; فارسية: ابوعلی ابن سینا) | Frunzensky (Фрунзенский) | 62.2 | 326,100 | Salimzoda Nusratullo Faizullo |

| Ferdowsi (بالطاجيكية: Фирдавсӣ, Firdavsi; فارسية: فردوسی) | Central (Центральный) | 54.5 | 209,000 | Yusufi Muhammadrahim |

| Shah Mansur (بالطاجيكية: Шоҳмансур, Shohmansur; فارسية: شاه منصور)[91] | Railway (Железнодорожный) | 48.9 | 162,600 | Bilol Ibrohim |

In 2020, the city's boundaries were expanded to take in land from Rudaki District in the southwest.[89]

| Land | Area (ha)[89] |

|---|---|

| Irrigated land | 2,091.75 |

| Orchards | 145.21 |

| Silk gardens | 12.28 |

| Citrus orchards | 2.10 |

| Pastures | 25.79 |

| Settlements | 6390.85 |

| Private farms/gardens | 65.79 |

| Swamp | 3.7 |

| Bush thickets | 1372.0026 |

| Reservoirs | 1436.66 |

| Underground passages | 310.2 |

| Construction | 7227.51 |

| Land not used for agriculture | 1235.03 |

السياحة

كما تشتهر بروعة جمالها ومناخها الطبيعي ، فهي كثيرة الأشجار وخضرتها تزين كل المدينة . – كما تشتهر بكثرة الأماكن السياحية ، والتي يتوفر فيها مراكز للعلاج الصحي الطبيعي، والتي يزورها كثير من الناس والسيّاح الأجانب كمنطقة حاجي أبي قارم.

أشهر أبنائها

من أشهر علمائها:

تشتهر بكثرة أسواقها ، والتي لا يستطيع الزائر لها إلا أن يتسوق فيها ، فهي تحتوي على ألذّ أنواع الفواكه والخضراوات وأطيبها ، حيث تسقى من مياه عذبه ، تشتهر بكثرة مائها وكثر العيون العذبة والساخنة للعلاج الطبيعي . – فيها يصدر أكثر من عشرين جريدة ومجلة محلية ، والتي من أهمها منبر الشعب ، وصدى الشرق ، أسيا + ، دوشنبه المسائية ، نجاة .

الاسم

سميت بدوشنبه نسبة لنهر دوشنبه، والذي يجري من شمالها إلى جنوبها.

أهم المعالم الإسلامية

- الجامع الكبير بإسم حاجي يعقوب ، والذي أسس قبل مائتين سنة، ويقع في قلب العاصمة ، ويسع لأكثر من ثلاثة ألف مصل ، والذي يتميز بقبته ومآذنه العاليا .

- معهد أبو حنيفة الإسلامية ، وهو من أهم المعالم الإسلامية العلمية، حيث يدرس فيه حاليا أكثر من أربعمائة طالب وطالبة العلوم الشرعية ، كما يوجد فيها كلية خاصة لتحفيظ القرآن ويتخرج منه المتخصصون والذين يعملون كأئمة أو معلمين في المدارس الدينية المنتشرة داخل الجمهورية.

- مسجد شاه منصور والذي يقع في وسط المدينة، والذي يعد من أبرز المساجد.

- المركز الإسلامي، والذي سيبنى بدعم من دولة قطر ، ويعتبر من أكبر المراكز الإسلامية، حيث يستوعب أكثر من سبعين ألف ، ويضم في داخله مسجدا ومكتبة ومدرسة ومعهد وصالات للمحاضرات والدرس .

احتفلت مدينة دوشنبه في عام 2009م بذكرى الإمام الأعظم أبي حنيفة النعمان بن ثابت ، والذي كان في شكل احتفال دولي شارك فيه ضيوف من أكثر من خمسين دولة ، وكان اغلبهم من البلاد الإسلامية ، والذي كان تحت رعاية فخامة رئيس الدولة .

ستحتفل دوشنبه في عام 2010م بالذكرى 1200 سنة لإمام الحديث والمحدّثين إسماعيل ابن محمد المشهور بالإمام البخاري.

برعاية فخامة رئيس الدولة تم ترجمة وطبع معاني القرآن باللغة التاجيكية ، ووزعت على المواطنين .

تشتهر بحركة الترجمة لكثير من الكتب الإسلامية والثقافية والتاريخية ، والتي تباع بكل حرية في المكتبات المنتشرة في كل مدن الجمهورية.

تشتهر بوفرة المخطوطات والآثار العلمية التاريخية الإسلامية ، والتي صمم لها مركز علمي متخصص للحفاظ عليها.

- Main sights of Dushanbe

القواعد العسكرية

توجد قاعدة عسكرية هندية علي بعد 80 كم جنوب المدينة. وهي القاعدة الهندية الوحيدة الموجودة خارج الهند. ويكثر في العاصمة تواجد جنود من قوات أجنبية، من الجيش الفرنسي الجيش الأمريكي والجيش الروسي.

الإعلام

الصحف والمجلات

The first newspaper published in Tajik was Bukhara Sharif in Kagan on 11 March 1912 and published by leaders of the Jadid movement like Mirzo Jalol Yusufzoda. The purpose of the newspaper was to "be a scientific, literary, directional, subject, and economic publication that will strive for the spread of civilization and the idea." Soon after, however, Ivan Petrov requested that the Emir of Bukhara close the paper, which he did on 2 January 1913.[94]

المدن الشقيقة

حالياً، لدوشنبه عدة مدن شقيقة:[95]

Ankara, Turkey

Ankara, Turkey Ashgabat, Turkmenistan

Ashgabat, Turkmenistan Boulder, United States

Boulder, United States Hainan, China

Hainan, China Klagenfurt, Austria

Klagenfurt, Austria Lahore, Pakistan

Lahore, Pakistan Lusaka, Zambia

Lusaka, Zambia Mazar-i-Sharif, Afghanistan

Mazar-i-Sharif, Afghanistan Minsk, Belarus

Minsk, Belarus Monastir, Tunisia

Monastir, Tunisia Qingdao, China

Qingdao, China Reutlingen, Germany

Reutlingen, Germany Saint Petersburg, Russia

Saint Petersburg, Russia Sanaa, Yemen

Sanaa, Yemen Shiraz, Iran

Shiraz, Iran Tehran, Iran

Tehran, Iran Ürümqi, China

Ürümqi, China Xiamen, China

Xiamen, China

In 1982, Mary Hey and Sophia Stoller started an initiative to make Dushanbe a sister city of Boulder even though during that time they were on opposite sides of the Cold War. In 1987, the mayor of Dushanbe, Maksud Ikramov, officially made Boulder a sister city of Dushanbe. Exchange students, tourism, and art exchanges began between the two cities. The Tajik Teahouse was sent from Dushanbe to Boulder in 1990. During the civil war, Boulder sent humanitarian aid to Dushanbe.[96]

المؤتمرات الدولية

Many international conferences have been held in Dushanbe, such as the International Conference on Integrated TB Control in Central Asia[97] and the hosting of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization conference in 2000, 2008, and 2014[98][99][100]

In 2003, Dushanbe hosted the International Forum on Fresh Water which was attended by 50 states and organizations.[101][102]

From 20 to 23 June 2018 the High-Level International Conference on the International Decade for Action 'Water for Sustainable Development' was held in Dushanbe, which discussed the upcoming decade for action with regards to water.[103] A second conference on the same subject was planned to be held in June 2020.[104]

On 16–17 May 2019 a high-level conference entitled "Countering Terrorism and its Financing Through Illicit Drug Trafficking and Organized Crime" was held in Dushanbe and attended by more than 50 countries. It passed the Dushanbe declaration, which put the primary responsibility for fighting terrorism onto national governments. Other topics, such as drug smuggling, were also discussed.[105]

On 15 June 2019 the fifth summit of the Conference on Interaction and Confidence-Building Measures in Asia was held in Dushanbe. The Asian members of the organization discussed common interests on topics such as peace and security, terrorism, arms control, the Iran nuclear deal, poverty, economic development, and globalization.[106]

طالع ايضاً

الهامش

- ^ Population of the Republic of Tajikistan as of 1 January 2008, State Statistical Committee, Dushanbe, 2008 (بالروسية)

- ^ "About Dushanbe". U.S. Embassy in Tajikistan (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 2021-07-28.

- ^ "License Plates of Tajikistan". www.worldlicenseplates.com. Retrieved 2021-07-28.

- ^ D. Saimaddinov, S. D. Kholmatova, and S. Karimov, Tajik-Russian Dictionary, Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Tajikistan, Rudaki Institute of Language and Literature, Scientific Center for Persian-Tajik Culture, Dushanbe, 2006.

- ^ Ranov, V. A. (Vadim Aleksandrovich) (1993). Dushanbe : gorod drevniĭ (PDF) (in الروسية). Solovʹev, V. S. (Viktor Stepanovich), Masov, R. M. (Rakhim Masovich). Dushanbe: Izd-vo "Donish". p. 15. ISBN 5-8366-0427-4. OCLC 32311792.

- ^ Ranov, V. A. (Vadim Aleksandrovich) (1993). Dushanbe : gorod drevniĭ (PDF) (in الروسية). Solovʹev, V. S. (Viktor Stepanovich), Masov, R. M. (Rakhim Masovich). Dushanbe: Izd-vo "Donish". p. 100. ISBN 5-8366-0427-4. OCLC 32311792.

- ^ "Hissar Culture". TheFreeDictionary.com. Retrieved 2020-08-02.

- ^ Ranov, V. A. (Vadim Aleksandrovich) (1993). Dushanbe : gorod drevniĭ (PDF) (in الروسية). Solovʹev, V. S. (Viktor Stepanovich), Masov, R. M. (Rakhim Masovich). Dushanbe: Izd-vo "Donish". pp. 21, 25. ISBN 5-8366-0427-4. OCLC 32311792.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح "Краткая историческая справка" (in الروسية). 2008-12-01. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008. Retrieved 2020-08-02.

- ^ Ranov, V. A. (Vadim Aleksandrovich) (1993). Dushanbe : gorod drevniĭ (PDF) (in الروسية). Solovʹev, V. S. (Viktor Stepanovich), Masov, R. M. (Rakhim Masovich). Dushanbe: Izd-vo "Donish". pp. 107–108. ISBN 5-8366-0427-4. OCLC 32311792.

- ^ Ranov, V. A. (Vadim Aleksandrovich) (1993). Dushanbe : gorod drevniĭ (PDF) (in الروسية). Solovʹev, V. S. (Viktor Stepanovich), Masov, R. M. (Rakhim Masovich). Dushanbe: Izd-vo "Donish". p. 27. ISBN 5-8366-0427-4. OCLC 32311792.

- ^ Yavan, Oxford Art Online. Macy, Laura Williams. [Basingstoke, England]: Macmillan. 2002. ISBN 1-884446-05-1. OCLC 50959350.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح "Regions: Dushanbe & Surroundings". Official Website of the Tourism Authority of Tajikistan. Committee of Youth Affairs, Sports and Tourism. Archived from the original on 22 November 2012. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ أ ب ت ث M., Davidzon (1983). Dushanbe, a guide. Raduga. pp. 10–11. OCLC 11399951.

- ^ Ranov, V. A. (Vadim Aleksandrovich) (1993). Dushanbe : gorod drevniĭ (PDF) (in الروسية). Solovʹev, V. S. (Viktor Stepanovich), Masov, R. M. (Rakhim Masovich). Dushanbe: Izd-vo "Donish". p. 110. ISBN 5-8366-0427-4. OCLC 32311792.

- ^ أ ب "Southern Tajikistan in Kushana period". National Museum of Antiquities of Tajikistan. Retrieved 2020-08-02.

- ^ "Historical Sketch". Dushanbe : ėnt︠s︡iklopedii︠a︡ (in الروسية). Dinorshoev, Muso. Dushanbe: Glavnai︠a︡ nauchnai︠a︡ redakt︠s︡ii︠a︡ Tadzhikskoĭ nat︠s︡ionalʹnoĭ ėnt︠s︡iklopedii. 2004. ISBN 5-89870-071-4. OCLC 65068362. Archived from the original on 28 October 2010.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Ranov, V. A. (Vadim Aleksandrovich) (1993). Dushanbe : gorod drevniĭ (PDF) (in الروسية). Solovʹev, V. S. (Viktor Stepanovich), Masov, R. M. (Rakhim Masovich). Dushanbe: Izd-vo "Donish". pp. 125–126. ISBN 5-8366-0427-4. OCLC 32311792.

- ^ Hiebert, F. T.; Kohl, P. L. (2012-10-20). "Garav kala: a Pleiades place resource". Pleiades: a gazetteer of past places. R. Talbert, T. Elliott, S. Gillies. Retrieved 2020-08-02.

- ^ Ranov, V. A. (Vadim Aleksandrovich) (1993). Dushanbe : gorod drevniĭ (PDF) (in الروسية). Solovʹev, V. S. (Viktor Stepanovich), Masov, R. M. (Rakhim Masovich). Dushanbe: Izd-vo "Donish". pp. 38–39. ISBN 5-8366-0427-4. OCLC 32311792.

- ^ Gariboldi, Andrea; Saripov, Abduvali (2012). "A Sasanian Hoard from Dushanbe" (PDF). Studia Iranica. 41: 169–186.

- ^ Довуди, Давлатходжа (January 2004). "Древние и средневековые монеты, найденные на территории города Душанбе". Древние и средневековые монеты, найденные на территории города Душанбе.

- ^ Litvinskiĭ, B. A. "Ajina Tepe". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved 2020-08-02.

- ^ Ranov, V. A. (Vadim Aleksandrovich) (1993). Dushanbe : gorod drevniĭ (PDF) (in الروسية). Solovʹev, V. S. (Viktor Stepanovich), Masov, R. M. (Rakhim Masovich). Dushanbe: Izd-vo "Donish". pp. 54–55, 85, 90. ISBN 5-8366-0427-4. OCLC 32311792.

- ^ "Illustrations" (PDF). p. 3.

- ^ Ranov, V. A. (Vadim Aleksandrovich) (1993). Dushanbe : gorod drevniĭ (PDF) (in الروسية). Solovʹev, V. S. (Viktor Stepanovich), Masov, R. M. (Rakhim Masovich). Dushanbe: Izd-vo "Donish". p. 133. ISBN 5-8366-0427-4. OCLC 32311792.

- ^ Ranov, V. A. (Vadim Aleksandrovich) (1993). Dushanbe : gorod drevniĭ (PDF) (in الروسية). Solovʹev, V. S. (Viktor Stepanovich), Masov, R. M. (Rakhim Masovich). Dushanbe: Izd-vo "Donish". p. 136. ISBN 5-8366-0427-4. OCLC 32311792.

- ^ Ranov, V. A. (Vadim Aleksandrovich) (1993). Dushanbe : gorod drevniĭ (PDF) (in الروسية). Solovʹev, V. S. (Viktor Stepanovich), Masov, R. M. (Rakhim Masovich). Dushanbe: Izd-vo "Donish". p. 170. ISBN 5-8366-0427-4. OCLC 32311792.

- ^ Turekulova, Natalia; Turekulov, Timur (2004–2005). "Tajikistan: A view from outside". Heritage at Risk. ICOMOS. ISSN 2365-5615.

- ^ Ranov, V. A. (Vadim Aleksandrovich) (1993). Dushanbe : gorod drevniĭ (PDF) (in الروسية). Solovʹev, V. S. (Viktor Stepanovich), Masov, R. M. (Rakhim Masovich). Dushanbe: Izd-vo "Donish". pp. 61, 144. ISBN 5-8366-0427-4. OCLC 32311792.

- ^ Ranov, V. A. (Vadim Aleksandrovich) (1993). Dushanbe : gorod drevniĭ (PDF) (in الروسية). Solovʹev, V. S. (Viktor Stepanovich), Masov, R. M. (Rakhim Masovich). Dushanbe: Izd-vo "Donish". p. 163. ISBN 5-8366-0427-4. OCLC 32311792.

- ^ Ranov, V. A. (Vadim Aleksandrovich) (1993). Dushanbe : gorod drevniĭ (PDF) (in الروسية). Solovʹev, V. S. (Viktor Stepanovich), Masov, R. M. (Rakhim Masovich). Dushanbe: Izd-vo "Donish". pp. 149–151. ISBN 5-8366-0427-4. OCLC 32311792.

- ^ "АҶАБ ШАҲРИ ДИЛОРОЙӢ" [The Wonderful City of Dushanbe]. Садои мардум (in Tajik (Cyrillic script)). 2013-04-19. Retrieved 2020-08-03.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Abdullaev, Kamoludin (2018). "Dushanbe". Historical Dictionary of Tajikistan. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 130–131. ISBN 978-1-5381-0252-7. OCLC 1049912411.

- ^ "Душанбе (столица Таджикистана)". Планета Земля (in الروسية). Retrieved 2020-09-18.

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماة:51 - ^ Rusu, Stefan; Dubovitskiy, Victor (2016). Spaces on the Run. Turkey. Istanbul: Dushanbe Art Ground. p. 31. ISBN 978-99947-892-7-6.

- ^ أ ب "Аҷаб шаҳри дилороӣ, Душанбе…". tiroz.org (in الروسية). 2019-07-19. Retrieved 2020-07-31.

- ^ "Urban Planning and Architecture". Dushanbe : ėnt︠s︡iklopedii︠a︡ (in الروسية). Dinorshoev, Muso. Dushanbe: Glavnai︠a︡ nauchnai︠a︡ redakt︠s︡ii︠a︡ Tadzhikskoĭ nat︠s︡ionalʹnoĭ ėnt︠s︡iklopedii. 2004. ISBN 5-89870-071-4. OCLC 65068362. Archived from the original on 28 October 2010.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Becker, Seymour. (1968). Russia's protectorates in Central Asia: Bukhara and Khiva, 1865-1924. Russian Research Center studies. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. 48–50.

- ^ Morrison, Alexander (2020). The Russian conquest of Central Asia : a study in imperial expansion, 1814-1914. Cambridge, UK. p. 255. ISBN 978-1-139-34338-1. OCLC 1224354503.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ ""Русский дом", "Заразка" и "Детский садик" - истории инфекционных больниц Душанбе | Новости Таджикистана ASIA-Plus". asiaplustj.info (in الروسية). Retrieved 2020-08-02.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د Вечёрка (2019-07-09). "Душанбе - столица края". Вечёрка (in الروسية). Retrieved 2020-08-01.

- ^ أ ب ت "A Tomb in Kabul: The Fate of the Last Amir of Bukhara and his country's relations with Afghanistan". Afghanistan Analysts Network - English. 2018-12-27. Retrieved 2020-07-31.

- ^ Bleuer, Christian (2013). Tajkistan: A Political and Social History. ANU Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-925021-15-8. OCLC 1076650077.

- ^ أ ب M., Davidzon (1983). Dushanbe, a guide. Raduga. pp. 13–14. OCLC 11399951.

- ^ Projorov, A. M. (1973–1982). "Dushanbe". Great Soviet Encyclopedia. Macmillan. OCLC 435381348.

- ^ "History". www.dushanbehotels.ru. Retrieved 2020-08-03.

- ^ أ ب "Dushanbe: History". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ "Бухарская Народная Советская Республика - это... Что такое Бухарская Народная Советская Республика?". Словари и энциклопедии на Академике (in الروسية). Retrieved 2020-08-03.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Atkin, Muriel. "Dushanbe". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Encyclopedia Iranica Foundation, Inc. Retrieved 2020-08-01.

- ^ Bleuer, Christian (2013). Tajkistan: A Political and Social History. Australian National University. p. 41. OCLC 940754059.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Abdullaev, Kamoludin (2018). "Chronology". Historical Dictionary of Tajikistan. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. xxviii–xxxvi. ISBN 978-1-5381-0252-7. OCLC 1049912411.

- ^ أ ب ت "Чтобы помнили. Русский Душанбе". Фергана.Ру (in الروسية). Archived from the original on 2020-08-04. Retrieved 2020-08-01.

- ^ Редакция. "Душанбе". Электронная еврейская энциклопедия ОРТ (in الروسية). Retrieved 2020-08-01.

- ^ Hughes, Katherine (2017-05-22). "From the Achaemenids to Somoni: national identity and iconicity in the landscape of Dushanbe's capitol complex". Central Asian Survey. 36 (4): 511–533. doi:10.1080/02634937.2017.1319796. ISSN 0263-4937. S2CID 149039948.

- ^ "Communication". Dushanbe : ėnt︠s︡iklopedii︠a︡ (in الروسية). Dinorshoev, Muso. Dushanbe: Glavnai︠a︡ nauchnai︠a︡ redakt︠s︡ii︠a︡ Tadzhikskoĭ nat︠s︡ionalʹnoĭ ėnt︠s︡iklopedii. 2004. ISBN 5-89870-071-4. OCLC 65068362. Archived from the original on 28 October 2010.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Times, Walter Duranty Wireless To the New York (1929-10-23). "Tajikistan Capital Becomes Stalinbad – Change Follows Elevation to Soviet Federal State – Regime Starts by Declaring an Amnesty". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-07-31.

- ^ M., Davidzon (1983). Dushanbe, a guide. Raduga. p. 44. OCLC 11399951.

- ^ أ ب ت Shermatov, Gafur. "Столица и ее градоначальники: кто был до Рустама Эмомали". Asia-Plus. Archived from the original on 13 February 2017.

- ^ "История Душанбе". Tajik Development Gateway на русском языке (in الروسية). Retrieved 2020-09-25.

- ^ DeYoung, Alan J.; Kataeva, Zumrad; Jonbekova, Dilrabo (2018), Huisman, Jeroen; Smolentseva, Anna; Froumin, Isak, eds., Higher Education in Tajikistan: Institutional Landscape and Key Policy Developments, Palgrave Studies in Global Higher Education, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 363–385, doi:, ISBN 978-3-319-52980-6

- ^ "CIA Information Report" (PDF). CIA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 January 2017.

- ^ "Дюшамбе - Сталинабад - Душанбе". Радио Озоди (in الروسية). Retrieved 2020-08-01.

- ^ "H-Diplo Roundtable XX-46 on Laboratory of Socialist Development: Cold War Politics and Decolonization in Soviet Tajikistan | H-Diplo | H-Net". networks.h-net.org. Retrieved 2020-08-01.

- ^ "Perspectives | Light and nostalgia in Tajikistan | Eurasianet". eurasianet.org. Retrieved 2020-08-01.

- ^ M., Davidzon (1983). Dushanbe, a guide. Raduga. p. 15. OCLC 11399951.

- ^ Nourzhanov, Kirill (2013). Tajikistan a political and social history. ANU E Press. p. 156. ISBN 978-1-925021-16-5. OCLC 984803513.

- ^ أ ب ت Nourzhanov, Kirill (2013). Tajikistan a political and social history. ANU E Press. pp. 180–183. ISBN 978-1-925021-16-5. OCLC 984803513.

- ^ Ethnic rioting in Dushanbe, New York Times, 13 February 1990. Retrieved 18 October 2008

- ^ أ ب Nourzhanov, Kirill (2013). "The Rise of Opposition, the Contraction of the State and the Road to Independence". Tajikistan a political and social history. ANU E Press. ISBN 978-1-925021-16-5. OCLC 984803513.

- ^ أ ب Bleuer, Christian (2013). "Epilogue: The Civil War of 1992". Tajkistan: A Political and Social History. ANU Press. pp. 327–329. ISBN 978-1-925021-15-8. OCLC 1076650077.

- ^ Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Refworld | Chronology for Russians in Tajikistan". Refworld. Retrieved 2020-08-03.

- ^ "The long echo of Tajikistan's civil war". openDemocracy. Archived from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 2020-08-03.

- ^ "Tajikistan and UNESCO Cooperation". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Tajikistan. 11 May 2019.

- ^ "Analysis: Dushanbe's Ex-Mayor One Of The Last Of Civil War Era". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Retrieved 2020-08-03.

- ^ "/ Исполнительный орган государственной власти города Душанбе". www.dushanbe.tj (in الروسية). Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- ^ "Пандемия нанесла огромный урон таджикской экономике. ВИДЕО". Радио Озоди (in الروسية). Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- ^ "Tajikistan: regime eternalization completed?". The Politicon. The Politicon. 26 January 2017. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج "Natural Conditions". Dushanbe : ėnt︠s︡iklopedii︠a︡ [Dushanbe Encyclopedia] (in الروسية). Dinorshoev, Muso. Dushanbe: Glavnai︠a︡ nauchnai︠a︡ redakt︠s︡ii︠a︡ Tadzhikskoĭ nat︠s︡ionalʹnoĭ ėnt︠s︡iklopedii. 2004. ISBN 5-89870-071-4. OCLC 65068362. Archived from the original on 28 October 2010.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ ХУРСАНД МИРЗОШОЕВИЧ, ТАЛБОНОВ. БИОТОПИЧЕСКОЕ РАСПРЕДЕЛЕНИЕ И ЭКОЛОГИЯ ПТИЦ ГОРОДА ДУШАНБЕ (PDF). pp. 17–22. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 February 2019. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- ^ ИСТОРИЯ СТАНОВЛЕНИЯ И РАЗВИТИЯ АРХИТЕКТУРЫ ОБЩЕСТВЕННЫХ ЗДАНИЙ ДУШАНБЕ (1924 началдх2000 гг.) (PDF). p. 13.

- ^ Hakimov, Farkhod; Domej, Gisela; Ischuk, Anatoly; Reicherter, Klaus; Cauchie, Lena; Havenith, Hans-Balder (2021-03-31). "Site Amplification Analysis of Dushanbe City Area, Tajikistan to Support Seismic Microzonation". Geosciences. 11 (4): 154. Bibcode:2021Geosc..11..154H. doi:10.3390/geosciences11040154. ISSN 2076-3263.

- ^ "Weather and Climate-The Climate of Dushanbe" (in الروسية). Weather and Climate. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- ^ "Klimatafel von Duschanbe / Tadschikistan" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961–1990) from stations all over the world (in الألمانية). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- ^ "Dushanbe Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- ^ Environmental Protection (2004). Dushanbe : ėnt︠s︡iklopedii︠a︡. Dinorshoev, Muso. Dushanbe: Glavnai︠a︡ nauchnai︠a︡ redakt︠s︡ii︠a︡ Tadzhikskoĭ nat︠s︡ionalʹnoĭ ėnt︠s︡iklopedii. ISBN 5-89870-071-4. OCLC 65068362. Archived from the original on 28 October 2010.

- ^ أ ب "/ Исполнительный орган государственной власти города Душанбе". www.dushanbe.tj. Retrieved 2020-08-02.

- ^ أ ب ت Вечёрка (2020-07-27). "География Душанбе в цифрах". Вечёрка (in الروسية). Retrieved 2020-09-18.

- ^ "Тақсимоти маъмурӣ / Сомонаи расмии Мақомоти иҷроияи ҳокимияти давлатии шаҳри Душанбе". www.dushanbe.tj. Retrieved 2020-08-02.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةAbout Dushanbe - ^ "Шиносномаи шаҳр / Сомонаи расмии Мақомоти иҷроияи ҳокимияти давлатии шаҳри Душанбе". dushanbe.tj. Retrieved 2021-04-07.

- ^ "Dushanbe travel guide". Caravanistan. Retrieved 2019-07-02.

- ^ Mulloev, Sharif (2009). Usmonov; Chigrin (eds.). История таджикской журналистики: учебно-методическое пособие для студентов отделения журналистики [History of Tajik journalism: a textbook for students of journalism.]. Dushanbe: Russian-Tajik (Slavic) University - Department of History and Theory of Journalism and Electronic Media.

- ^ "Бародаршаҳрҳо". dushanbe.tj (in الطاجيكية). Dushanbe. Retrieved 2021-01-19.

- ^ "Boulder Dushanbe Sister Cities". Boulder-Dushanbe Sis. Retrieved 2020-08-05.

- ^ "USAID and Ministry of Health Hold Third International Conference on Integrated TB Control in Central Asia". U.S. Embassy in Tajikistan. 2018-09-13. Retrieved 2020-08-10.

- ^ "Social and Political Life". Dushanbe : ėnt︠s︡iklopedii︠a︡. Dinorshoev, Muso. Dushanbe: Glavnai︠a︡ nauchnai︠a︡ redakt︠s︡ii︠a︡ Tadzhikskoĭ nat︠s︡ionalʹnoĭ ėnt︠s︡iklopedii. 2004. ISBN 5-89870-071-4. OCLC 65068362. Archived from the original on 28 October 2010.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Joint Statement of the Meeting of the Council of Heads of State of The Shanghai Cooperation Organization". www.fmprc.gov.cn. Retrieved 2020-09-28.

- ^ "13th annual summit of SCO starts today in Dushanbe". Dispatch News Desk. 2014-09-10. Retrieved 2021-04-12.

- ^ "Столица > Душанбе - столица > Официальный сайт Исполнительного органа местной государственной власти в городе Душанбе". 2010-11-21. Archived from the original on 21 November 2010. Retrieved 2020-09-16.

- ^ "MOFA: Statement by Mr. Keizo Takemi Representative of the Japanese Delegation at the Dushanbe International Fresh Water Forum". www.mofa.go.jp. Retrieved 2020-09-16.

- ^ ""Water for Sustainable Development" Conference in Dushanbe". UNRCCA. 2018-06-23. Retrieved 2020-08-10.

- ^ ""Dushanbe water process ". Second High-Level Conference on the International Decade for action "Water for Sustainable Development", 2018-2028". Embassy of the Republic of Tajikistan in Germany.

- ^ "UNRCCA and UNOCT Participated in the High-Level Conference "Countering Terrorism and Its Financing Through Illicit Drug Trafficking and Organized Crime" in Dushanbe, 16-17 May 2019". UNRCCA. 2019-05-20. Retrieved 2020-08-10.

- ^ "Terrorism 'gravest threat' people face in Asia: Jaishankar at CICA Summit". The Hindu. PTI. 2019-06-15. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 2021-03-05.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: others (link)

وصلات خارجية

| دوشنبه

]].- Dushanbe pictures through eyes of westerner

- Dushanbe street map

- Encyclopedia Iranica article on Dushanbe

- Dushanbe on wikimapia

- Tajik Web Gateway

- Dushanbe City Coat of Arms

- Boulder-Dushanbe Sister Cities

- Steam Locomotive in a Dushanbe Park near the main railway station

| الترتيب | الولاية | التعداد | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

دوشنبه  خوجند |

1 | دوشنبه | دوشنبه | 846,400 |  قرغانتپه  كولاب | ||||

| 2 | خوجند | صغد | 181,600 | ||||||

| 3 | قرغانتپه | خطلان | 110,800 | ||||||

| 4 | كولاب | خطلان | 105,500 | ||||||

| 5 | إستروشن | صغد | 64,600 | ||||||

| 6 | إسفرة | صغد | 59,500 | ||||||

| 7 | Vahdat | النواحي التابعة للجمهورية | 55,000 | ||||||

| 8 | Tursunzoda | النواحي التابعة للجمهورية | 53,700 | ||||||

| 9 | Konibodom | صغد | 52,200 | ||||||

| 10 | Panjakent | صغد | 42,800 | ||||||

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- CS1 الروسية-language sources (ru)

- CS1 maint: others

- CS1 Tajik (Cyrillic script)-language sources (tg-cyrl)

- CS1 maint: location missing publisher

- CS1 location test

- CS1 الألمانية-language sources (de)

- CS1 الطاجيكية-language sources (tg)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing طاجيكية-language text

- Articles containing روسية-language text

- Pages using infobox settlement with unknown parameters

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles containing فارسية-language text

- عواصم آسيا

- مدن طاجيكستان

- مدن في آسيا الوسطى

- دوشنبه

- De-Stalinization