جورج لوميتر

جورج لوميتر Georges Lemaître | |

|---|---|

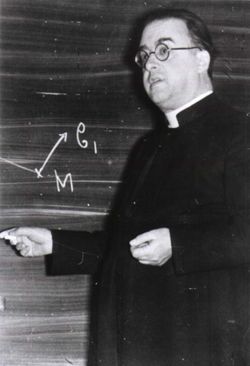

الراهب والعالم، مسيو جورج لوميتر. | |

| وُلِدَ | 17 يوليو 1894 |

| توفي | 20 يونيو 1966 |

| الجنسية | بلجيكي |

| المدرسة الأم | جامعة كمبردج |

| اللقب | نظرية تمدد الكون نظرية الانفجار العظيم إحداثيات لوميتر |

| السيرة العلمية | |

| المجالات | علم الكون الفيزياء الفلكية |

| الهيئات | الجامعة الكاثولكية في لوڤن |

| المشرف على الدكتوراه | هارلاو شيپلي |

| طلاب الدكتوراه | لويس فليپ بوكاريه |

| التوقيع | |

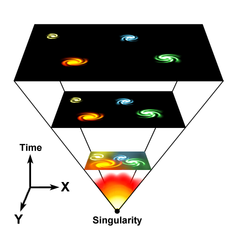

مسيو جورج هنري جوسف إدوار لوميتر (بالفرنسية: [ləmɛtʁ] (![]() استمع)؛ 17 يوليو 1894 - 20 يونيو 1966)، هو راهب، فلكي بلجيكي، وأستاذ الفيزياء في الجامعة الكاثوليكية في لوڤن.[1] كان لوميتر أول شخص يطرح نزرية تمدد الكون، والتي تُعزى إلى إدوين هبل.[2][3] وهو أيضاً أول من اشتق ما يعرف باسم قانون هبل وقام بأول تقدير لما يطلق عليه ثابت هبل، والذي نشره عام 1927، قبل سنتين من مقال هبل.[4][5][6][7] طرح لوميتر أيضاً ما اشتهر فيما بعد باسم نظرية الانفجار العظيم عن نشأة الكون، والذي أطلق عليها "فرضية الذرة البدائية".[8]

استمع)؛ 17 يوليو 1894 - 20 يونيو 1966)، هو راهب، فلكي بلجيكي، وأستاذ الفيزياء في الجامعة الكاثوليكية في لوڤن.[1] كان لوميتر أول شخص يطرح نزرية تمدد الكون، والتي تُعزى إلى إدوين هبل.[2][3] وهو أيضاً أول من اشتق ما يعرف باسم قانون هبل وقام بأول تقدير لما يطلق عليه ثابت هبل، والذي نشره عام 1927، قبل سنتين من مقال هبل.[4][5][6][7] طرح لوميتر أيضاً ما اشتهر فيما بعد باسم نظرية الانفجار العظيم عن نشأة الكون، والذي أطلق عليها "فرضية الذرة البدائية".[8]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

حياته

بعد تخرجه من المدرسة الثانوية اليسوعية، بدأ لوميتر دراسة الهندسة المدنية في الجامعة الكاثوليكية في لوڤن وكان في السابعة عشر من عمره. عام 1914، انقطع عن الدراسة ليخدم كضابط مدفعية في الجيش البلجيكي أثناء الحرب العالمية الثانية. عند انتهاء القتال، حصل على صليب الحرب البلجيكي.

بعد الحرب، درس الفيزياء والرياضيات، وبدأ الاستعداد للرهبنة. حصل على الدكتوارة عام 1920 وكان عنوان أطروحته l'Approximation des fonctions de plusieurs variables réelles (رسم المهام للمتغيرات الحقيقية المتعددة)، كتبها تحت اشراف شارل دو لا ڤالي-پوسين. رُسم كاهن عام 1923.

عام 1923، أصبح طالب دراسات عليا في قسم الفلك بجامعة كمبردج، وقضى عام في بيت سانت إدموند (حالياً كلية سانت إدمنود، كمبردج). عمل مع أرثر إدينگتون الذي علمه مبادئ علم الكون المعاصر، علم الفلك النجمي، والتحليل الرقمي. قضى السنة التالية في مرصد كلية هارڤرد في كمبردج، مساتشوستس، بصحبة هارلو شيپلي، الذي كان للتو قد حقق شهرة عن عمله على السدم، وفي معهد مساتشوستس للتكنولوجيا، حيث سجل للحصول على الدكتوراة في العلوم.

عام 1925، عاد إلى بلجيكا، وأصبح محاضر نصف وقت في الجامعة الكاثولكية في لوڤن. بعدها بدأ التقرير الذي حقق له شهرة دولية، نشره عام 1927 في Annales de la Société Scientifique de Bruxelles (حوليات الجمعية العلمية في بروكسل)، تحت اسم "Un Univers homogène de masse constante et de rayon croissant rendant compte de la vitesse radiale des nébuleuses extragalactiques" ("A homogeneous Universe of constant mass and growing radius accounting for the radial velocity of extragalactic nebulae").[9] في هذا التقرير، طرح فكرة جديدة عن الكون المتمدد (والذي اقتبس أيضاً في قانون هبل وقدم أول تقدير رصدي على ثابت هبل[10]) لكن حتى الآن لم يتم ذلك للذرة البدائية. عوضاً عن ذلك، فالحالة الأولية أخذت على أنها النموذج الكوني الثابت ذو الحجم المحدود، لإينشتاين. كان لهذا التقرير تأثير محدود لأن الجريدة التي نشرته كانت غير مقروءة كثيراً من قبل الفلكيين خارج بلجيكا، ترجم لوميتير مقاله للإنگليزية عام 1931 بمساعدة أرثر إدينگتون لكن الجزء المتعلقة بتقدير "ثابت هبل" لم يترجم في ورقة 1931، لأسباب غير مبررة حتى الآن.[11]

في ذلك الوقت، أينشتاين، الذي لم يأخذ بالاستثناءات الرياضية في نظرية لويمتر، رفض قبول فكرة الكون المتمدد؛ والذي أشار له لوميتر معلقاً "Vos calculs sont corrects, mais votre physique est abominable"[12] ("حساباتك صحيحة، لكن فيزيائك كريهة.") في العام نفسه، عاد لوميتر لمعهد مساتشوستس للتكنولوجيا ليقدم أطروحة الدكتوراة حول The gravitational field in a fluid sphere of uniform invariant density according to the theory of relativity. بعد حصول على الدكتوراة، أصبح أستاذ اعتيادي في الجامعة الكاثولكية في لوڤن.

عام 1930، نشر إدينگتون في الإشعارات الشهرية للجمعية الفلكية الملكية تعليق طوليق عن مقال لوميتر 1927، وصف فيه الأخير بأنه "حل متألق" لمشكلات الكون العالقة.[13] The original paper was published in an abbreviated English translation in 1931, along with a sequel by Lemaître responding to Eddington's comments.[14] بعدها دُعي لوميتر إلى لندن للمشاركة في اجتماع الرابطة البريطانية حول العلاقة بين الكون الفيزيائي والروحانية. هناك طرح أن الكون تمدد من النقطة الأولية، والتي أطلق عليها "الذرة البدائية" وتطور في تقريرنشره في ناتشر.[15] وصف لوميتر نفسه نظريته على أنها "بيضة كونية إنفجرت لحظة الخلق"، وأصبحت تعرف فيما بعد باسم "نظرية الانفجار العظيم"، مصطلح وصفي وضعه فرد هويل الذي كان مؤيداً لحالة استقرار الكون.

This proposal met skepticism from his fellow scientists at the time. Eddington found Lemaître's notion unpleasant. Einstein found it suspect because he deemed it unjustifiable from a physical point of view. On the other hand, Einstein encouraged Lemaître to look into the possibility of models of non-isotropic expansion, so it is clear he was not altogether dismissive of the concept. He also appreciated Lemaître's argument that a static-Einstein model of the universe could not be sustained indefinitely into the past.

In January 1933, Lemaître and Einstein, who had met on several occasions—in 1927 in Brussels, at the time of a Solvay Conference, in 1932 in Belgium, at the time of a cycle of conferences in Brussels and lastly in 1935 at Princeton—traveled together to California for a series of seminars. After the Belgian detailed his theory, Einstein stood up, applauded, and is supposed to have said, "This is the most beautiful and satisfactory explanation of creation to which I have ever listened."[بحاجة لمصدر] However there is disagreement over the reporting of this quote in the newspapers of the time, and it may be that Einstein was not actually referring to the theory as a whole but to Lemaître's proposal that cosmic rays may in fact be the leftover artifacts of the initial "explosion". Later research on cosmic rays by Robert Millikan would undercut this proposal, however.

In 1933, when he resumed his theory of the expanding Universe and published a more detailed version in the Annals of the Scientific Society of Brussels, Lemaître would achieve his greatest glory. Newspapers around the world called him a famous Belgian scientist and described him as the leader of the new cosmological physics.

On 17 March 1934, Lemaître received the Francqui Prize, the highest Belgian scientific distinction, from King Léopold III. His proposers were Albert Einstein, Charles de la Vallée-Poussin and Alexandre de Hemptinne. The members of the international jury were Eddington, Langevin and Théophile de Donder. Another distinction that the Belgian government reserves for exceptional scientists was allotted to him in 1950: the decennial prize for applied sciences for the period 1933–1942.[بحاجة لمصدر]

In 1936, he was elected member of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences. He took an active role there, becoming its president in March 1960 and remaining so until his death. During Vatican II he was asked to serve on the first special commission to examine the question of contraception. However, as he could not travel to Rome because of his health (he had suffered a heart attack in December 1964), Lemaître demurred, expressing his surprise that he was even chosen, at the time telling a Dominican colleague, P. Henri de Riedmatten, that he thought it was dangerous for a mathematician to venture outside of his speciality.[16] He was also named prelate (Monsignor) in 1960 by Pope John XXIII.

In 1941, he was elected member of the Royal Academy of Sciences and Arts of Belgium.[بحاجة لمصدر]

In 1946, he published his book on L'Hypothèse de l'Atome Primitif (The Primeval Atom Hypothesis). It would be translated into Spanish in the same year and into English in 1950.[بحاجة لمصدر]

By 1951, Pope Pius XII declared that Lemaître's theory provided a scientific validation for Creationism and Catholicism. However, Lemaître resented the Pope's proclamation.[17][18] When Lemaître and Daniel O'Connell, the Pope's science advisor, tried to persuade the Pope not to mention Creationism publicly anymore, the Pope agreed. He convinced the Pope to stop making proclamations about cosmology.[19] While a devoted Roman Catholic, he was against mixing science with religion.[20]

In 1953, he was given the inaugural Eddington Medal awarded by the Royal Astronomical Society.[21][22]

During the 1950s, he gradually gave up part of his teaching workload, ending it completely with his éméritat in 1964.

At the end of his life, he was devoted more and more to numerical calculation. He was in fact a remarkable algebraicist and arithmetical calculator. Since 1930, he used the most powerful calculating machines of the time, the Mercedes. In 1958 he was introduced to the University's Burroughs E 101, its first electronic computer. Lemaître maintained a strong interest in the development of computers and, even more, in the problems of language and computer programming. Throughout his latter years these were abiding interests until they absorbed him almost completely.

He died on 20 June 1966, shortly after having learned of the discovery of cosmic microwave background radiation, which provided further evidence for his intuitions about the birth of the Universe.

In 2005, Lemaître was voted to the 61st place of [De Grootste Belg] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) ("The Greatest Belgian"), a Flemish television program on the VRT. In the same year he was voted to the 78th place by the audience of the [Le plus grand Belge] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) ("The Greatest Belgian"), a television show of the RTBF.

أعماله

كان لومتر رائدا في تطبيق النظرية النسبية العامة لأينشتاين في علم الكون. وفي عام 1927 سبق مقالة إدوين هابل الشهيرة بسنتين كاملتين ، حيث استطاع لومتر صياغة ما عُرف بعد ذلك بقانون هابل ووصفها بأنها ظاهرة أساسية في استخدامها في علم الكون مع تطبيق النظرية النسبية، كما استطاع حساب لثابت هابل، إلا أن لم يستطع إثبات أنها علاقة خطية بين بعد المجرات والانزياح الأحمر بسبب عدم توفر نتائج إلقياسات الفعلية آنذاك وقام بها هابل في ذلك الوقت وقام بنشرها في عام 1929.

وكان فريدمان يعيش في الاتحاد السوفييتي وتوفي عام 1925 مباشرة بعد اقتراحه لنظرية تعرف الآن بنظرية فريدمان-لومتر-روبرتسون-واكر. ونظرا لأن أمضى لومتر معظم حياته في أوروبا فهو لم يكن معروفا في الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية مثل إدوين هابل وأينشتاين، ومع ذلك فقد غيرت نظرية لومتر علم الفلك تغييرا جذريا. وذلك لأن لومتر بالإضافة إلى نبوغه فقد كان ملما بالآتي:

- كان ملما بأعمال الفلكيين وصاغ نظريته بحيث تستطيع أن تتمشى مع ماتأتي به المشاهدة العملية التي كانت متاحة في ذلك الوقت، وعلى الأخص فهم ظاهرة الانزياح الأحمر للمجرات والعلاقة الخطية بين مسافات المجرات بالنسبة غلينا وسرعتها،

- وقام بصياغة نظريته في الوقت المناسب حيث كان غدوين عابل على وشك القيام بنشر العلاقة بين المسافة وسرعة المجرات، والتي عززت تمدد الكون، وبالتالي تؤدي إلى نظرية الانفجار العظيم.

- كما أنه درس على يد ارثر إدنگتون الذي أيده وجعل العلميين آنذاك يهتمون بأعمال لومتر العلمية.

وكل من جورج لومتر وألكسندر فريدمان اقترح كونا يمكن وصفه ب النظرية النسبية العامة وأنه كون يتمدد ويتسع. ولكن لومتر كان هو الأول الذي رأى أن تمدد الكون يفسر الانزياح الأحمر لخطوط طيف المجرات. وهو أول من استنتج أن شيئا يمكن وصفه بأنه عملية خلق أدت إلى تكوين الكون في الماضي.

وتوفي جورج لومتر في 29 يونيو 1966 بعد أن اكتـُشف إشعاع الخلفية الميكروني الكوني والذي أتى بتأييد عملي إضافي إلى نظرية لومتر عن نشأة الكون.

وقام كل من ألان جوت وأندري ليندا في عام 1980 بإجراء تعديل في نظرية لومتر بأن أضافا إليها مرحلة تضخم كوني أو انتفاخ كوني.

أشياء على اسمه

- فهوة القمر لوميتر

- كون فريدمان-لوميتر-روبرتسون-والكر

- أحداثيات لوميتر

- Lemaître observers in the Schwarzschild vacuum Frame fields in general relativity

- كويكب لويمتر 1565

- The fifth Automated Transfer Vehicle, Georges Lemaître ATV

- Norwegian indie electronic band Lemaitre (band)

المراجع

- G. Lemaître, Discussion sur l'évolution de l'univers, 1933

- G. Lemaître, L'Hypothèse de l'atome primitif, 1946

- G. Lemaître, The Primeval Atom - an Essay on Cosmogony, D. Van Nostrand Co, 1950.

- "The Primeval Atom," in Munitz, Milton K., ed., Theories Of The Universe, The Free Press, 1957.

- Lemaître, G. (1931). "The Evolution of the Universe: Discussion". Nature. 128 (3234): 699–701. Bibcode:1931Natur.128..704L. doi:10.1038/128704a0.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lemaître, G. (1927). "Un univers homogène de masse constante et de rayon croissant rendant compte de la vitesse radiale des nébuleuses extragalactiques". Annals of the Scientific Society of Brussels. 47A: 41.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) (بالفرنسية)

- (Translated in: "A Homogeneous Universe of Constant Mass and Growing Radius Accounting for the Radial Velocity of Extragalactic Nebulae". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 91: 483–490. 1931. Bibcode:1931MNRAS..91..483L.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help))

- (Translated in: "A Homogeneous Universe of Constant Mass and Growing Radius Accounting for the Radial Velocity of Extragalactic Nebulae". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 91: 483–490. 1931. Bibcode:1931MNRAS..91..483L.

- G. Lemaître (1931-05-09). "The Beginning of the World from the Point of View of Quantum Theory". Nature. 127 (3210). Bibcode:1931Natur.127..706L. doi:10.1038/127706b0. Retrieved 2012-02-28.

انظر أيضاً

المصادر

- ^ "Obituary: Georges Lemaitre". Physics Today. 19 (9): 119. September 1966. doi:10.1063/1.3048455.

- ^ http://www.nature.com/news/2011/110627/full/news.2011.385.html

- ^ http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v479/n7372/full/479171a.html#/ref2

- ^ Sidney van den Bergh arxiv.org 6 Jun 2011 قالب:Arxiv [physics.hist-ph]

- ^ David L. Block arxiv.org 20 Jun 2011 & 8 Jul 2011 قالب:Arxiv [physics.hist-ph]

- ^ Eugenie Samuel Reich Published online 27 June 2011| Nature| DOI:10.1038/news.2011.385

- ^ http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v479/n7372/full/479171a.html

- ^ A Science Odyssey: People and Discoveries: Big bang theory is introduced

- ^ G. Lemaître (1927). "Un Univers homogène de masse constante et de rayon croissant rendant compte de la vitesse radiale des nébuleuses extra-galactiques" (PDF). Annales de la Société Scientifique de Bruxelles (in French). 47: 49. Bibcode:1927ASSB...47...49L.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Ari Belenkiy: Alexander Friedmann and the origins of modern cosmology. Phys. Today 65(10), 38 (2012); doi: 10.1063/PT.3.1750

- ^ Michael Way1 and Harry Nussbaumer Published online August 2011| Physics Today| DOI:10.1063/PT.3.1194

- ^ Deprit, A. (1984). "Monsignor Georges Lemaître". A. Barger (ed) The Big Bang and Georges Lemaître: 370, Reidel.

- ^ Eddington, A. S., "On the instability of Einstein's spherical world", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Vol. 90, p.668-688, 05/1930

- ^ Lemaître, G., "Expansion of the universe, The expanding universe", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Vol. 91, p.490-501, 03/1931

- ^ G. Lemaître, The Beginning of the World from the Point of View of Quantum Theory, Nature 127 (1931), n. 3210, pp. 706. DOI:10.1038/127706b0 قالب:Bibcode

- ^ Lambert, Dominique, 2000. Un Atome d'Univers. Lessius, p. 302.

- ^ Peter T. Landsberg (1999). Seeking Ultimates: An Intuitive Guide to Physics, Second Edition. CRC Press. p. 236. ISBN 9780750306577.

Indeed the attempt in 1951 by Pope Pius XII to look forward to a time when creation would be established by science, was resented by several physicists, notably by George Gamow and even George Lemaitre, a member of the Pontifical Academy.

- ^ "Georges Lemaître, Father of the Big Bang". COSMIC HORIZONS: ASTRONOMY AT THE CUTTING EDGE. American Museum of Natural History. 2000. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

It is tempting to think that Lemaître's deeply-held religious beliefs might have led him to the notion of a beginning of time. After all, the Judeo-Christian tradition had propagated a similar idea for millennia. Yet Lemaître clearly insisted that there was neither a connection nor a conflict between his religion and his science. Rather he kept them entirely separate, treating them as different, parallel interpretations of the world, both of which he believed with personal conviction. Indeed, when Pope Pius XII referred to the new theory of the origin of the universe as a scientific validation of the Catholic faith, Lemaître was rather alarmed.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Simon Singh (2010). Big Bang. HarperCollins UK. p. 362. ISBN 9780007375509.

Lemaître was determined to discourage the Pope from making proclamations about cosmology, partly to halt the embarrassment that was being caused to supporters of the Big Bang, but also to avoid any potential difficulties for the Church. ...Lemaître contacted Daniel O'Connell, director of the Vatican Observatory and the Pope's science advisor, and suggested that together they try to persuade the Pope to keep quiet on cosmology. The Pope was surprisingly compliant and agreed to the request - the Big Bang would no longer be a matter suitable for Papal addresses.

- ^ Simon Singh (2010). Big Bang. HarperCollins UK. p. 362. ISBN 9780007375509.

It was Lemaître's firm belief that scientific endeavour should stand isolated from the religious realm. With specific regard to his Big Bang theory, he commented: 'As far as I can see, such a theory remains entirely outside any metaphysical or religious question.' Lemaître had always been careful to keep his parallel careers in cosmology and theology on separate tracks, in the belief that one led him to a clearer comprehension of the material world, while the other led to a greater understanding of the spiritual realm... ...Not surprisingly, he was frustrated and annoyed by the Pope's deliberate mixing of theology and cosmology. One student who saw Lemaître upon his return from hearing the Pope's address to the Academy recalled him 'storming into class...his usual jocularity entirely missing'.

- ^ http://www.ras.org.uk/awards-and-grants/awards/269?task=view

- ^ Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Vol. 113, p.2

قراءات إضافية

- Berenda, Carlton W. (1951) "Notes on Lemaître's Cosmogony", The Journal of Philosophy Vol. 48, No. 10.

- Berger, André (1984) The Big Bang and Georges Lemaître, D. Reidel.

- Cevasco, George A. (1954) "The Universe and Abbe Lemaitre", Irish Monthly Vol. 83, No. 969.

- Godart, Odon & Heller, Michal (1985) Cosmology of Lemaître, Pachart Publishing House.

- Holder, R. D. & Mitton, S. (2013) George Lemaître: Life, Science and Legacy, Astrophysics and Space Science Vol. 395, Springer.

- McCrea, William H. (September–October 1970) "Cosmology Today: A Review of the State of the Science with Particular Emphasis on the Contributions of Georges Lemaître", American Scientist Vol. 58, No. 5.

- Nussbaumer, Harry; Bieri, Lydia; Sandage, Allan (2009). Discovering the Expanding Universe. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-51484-2.

- Kragh, Helge (1970). "Georges Lemaître" (PDF). In Gillispie, Charles (ed.). Dictionary of Scientific Biography. New York: Scribner & American Council of Learned Societies. pp. 542–543. ISBN 978-0-684-10114-9.

- Turek, Jósef. Georges Lemaître and the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, Specola Vaticana, 1989.

وصلات خارجية

- 'A Day Without Yesterday': Georges Lemaître & the Big Bang

- Biography: The Day Without Yesterday: Lemaître, Einstein and the Birth of Modern Cosmology.

- December 1932 article in Modern Mechanics explaining the Big Bang theory of Abbe George Lemaître, Belgian mathematician.

- جورج لوميتر at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- Biography with signature

- Pages using infobox scientist with unknown parameters

- Articles containing فرنسية-language text

- Articles with unsourced statements from August 2010

- Lang and lang-xx template errors

- نسبيون

- أكاديميون بلجيكيون

- فلكيون بلجيكيون

- رهبان كاثوليك بلجيكيون

- علماء بلجيكيون

- نظرية الانفجار العظيم

- علماء كون

- أعضاء أكاديمية العلوم الپاپوية

- خريجو الجامعة الكاثوليكية في لوڤن (قبل -1968)

- خريجو جامعة كمبردج

- طاقم تدريس جامعة هارڤرد

- مواليد 1894

- وفيات 1966

- علماء-رجال دين كاثوليك

- أشخاص من حركة والون

- ناشطو حركة والون

- أشخاص من شارلروا

- أشخاص من لوڤن

- Recipients of the Croix de Guerre (Belgium)