لاما

| لاما | |

|---|---|

| |

Domesticated

| |

| التصنيف العلمي | |

| أصنوفة غير معروفة (أصلحها): | Lama |

| Species: | Template:Taxonomy/LamaL. glama

|

| Binomial name | |

| Template:Taxonomy/LamaLama glama | |

| |

| Domestic llama and alpaca range[1] | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Camelus glama Linnaeus, 1758 | |

The llama ( /ˈlɑːmə/; النطق الإسپاني: [ˈʎama] or النطق الإسپاني: [ˈʝama]) (Lama glama) is a domesticated South American camelid, widely used as a meat and pack animal by Andean cultures since the pre-Columbian era.

Llamas are social animals and live with others as a herd. Their wool is soft and contains only a small amount of lanolin.[2] Llamas can learn simple tasks after a few repetitions. When using a pack, they can carry about 25 to 30% of their body weight for 8 to 13 km (5–8 miles).[3] The name llama (in the past also spelled "lama" or "glama") was adopted by European settlers from native Peruvians.[4]

The ancestors of llamas are thought to have originated from the Great Plains of North America about 40 million years ago, and subsequently migrated to South America about three million years ago during the Great American Interchange. By the end of the last ice age (10,000–12,000 years ago), camelids were extinct in North America.[3] As of 2007, there were over seven million llamas and alpacas in South America and over 158,000 llamas and 100,000 alpacas, descended from progenitors imported late in the 20th century, in the United States and Canada.[5]

In Aymara mythology, llamas are important beings. The Heavenly Llama is said to drink water from the ocean and urinates as it rains.[6] According to Aymara eschatology, llamas will return to the water springs and ponds where they come from at the end of time.[6]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Classification

Lamoids, or llamas (as they are more generally known as a group), consist of the vicuña (Vicugna vicugna, prev. Lama vicugna), guanaco (Lama guanicoe), Suri alpaca, and Huacaya alpaca (Vicugna pacos, prev. Lama guanicoe pacos), and the domestic llama (Lama glama). Guanacos and vicuñas live in the wild, while llamas and alpacas exist only as domesticated animals.[7] Although early writers compared llamas to sheep, their similarity to the camel was soon recognized. They were included in the genus Camelus along with alpaca in the Systema Naturae (1758) of Carl Linnaeus.[8] They were, however, separated by Georges Cuvier in 1800 under the name of lama along with the guanaco.[9] DNA analysis has confirmed that the guanaco is the wild ancestor of the llama, while the vicuña is the wild ancestor of the alpaca; the latter two were placed in the genus Vicugna.[10]

The genera Lama and Vicugna are, with the two species of true camels, the sole existing representatives of a very distinct section of the Artiodactyla or even-toed ungulates, called Tylopoda, or "bump-footed", from the peculiar bumps on the soles of their feet. The Tylopoda consist of a single family, the Camelidae, and shares the order Artiodactyla with the Suina (pigs), the Tragulina (chevrotains), the Pecora (ruminants), and the Whippomorpha (hippos and cetaceans, which belong to Artiodactyla from a cladistic, if not traditional, standpoint). The Tylopoda have more or less affinity to each of the sister taxa, standing in some respects in a middle position between them, sharing some characteristics from each, but in others showing special modifications not found in any of the other taxa.[بحاجة لمصدر]

The 19th-century discoveries of a vast and previously unexpected extinct Paleogene fauna of North America, as interpreted by paleontologists Joseph Leidy,[11] Edward Drinker Cope,[12] and Othniel Charles Marsh, aided understanding of the early history of this family.[بحاجة لمصدر] Llamas were not always confined to South America; abundant llama-like remains were found in Pleistocene deposits in the Rocky Mountains and in Central America. Some of the fossil llamas were much larger than current forms. Some species remained in North America during the last ice ages. North American llamas are categorized as a single extinct genus, Hemiauchenia. Llama-like animals would have been a common sight 25,000 years ago, in modern-day California, Texas, New Mexico, Utah, Missouri, and Florida.[13]

The camelid lineage has a good fossil record. Camel-like animals have been traced from the thoroughly differentiated, modern species back through early Miocene forms. Their characteristics became more general, and they lost those that distinguished them as camelids; hence, they were classified as ancestral artiodactyls.[14] No fossils of these earlier forms have been found in the Old World, indicating that North America was the original home of camelids, and that the ancestors of Old World camels crossed over via the Bering Land Bridge from North America. The formation of the Isthmus of Panama three million years ago allowed camelids to spread to South America as part of the Great American Interchange, where they evolved further. Meanwhile, North American camelids died out at the end of the Pleistocene.[15]

Characteristics

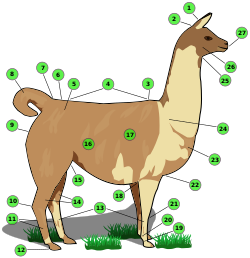

A full-grown llama can reach a height of 1.7 to 1.8 m (5 ft 7 in to 5 ft 11 in) at the top of the head, and can weigh between 130 and 272 kg (287 and 600 lb).[16] At maturity, males can weigh 94.74 kg, while females can weigh 102.27 kg.[17] At birth, a baby llama (called a cria) can weigh between 9 and 14 kg (20 and 31 lb). Llamas typically live for 15 to 25 years, with some individuals surviving 30 years or more.[18][19][20][مطلوب مصدر أفضل]

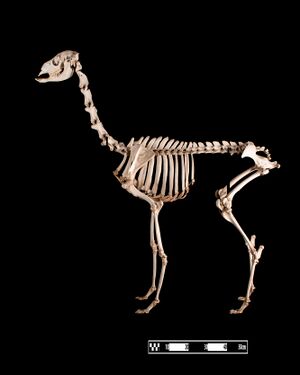

The following characteristics apply especially to llamas. Dentition of adults: incisors 1/3 canines 1/1, premolars 2/2, molars 3/3; total 32. In the upper jaw, a compressed, sharp, pointed laniariform incisor near the hinder edge of the premaxilla is followed in the male at least by a moderate-sized, pointed, curved true canine in the anterior part of the maxilla.[21] The isolated canine-like premolar that follows in the camels is not present. The teeth of the molar series, which are in contact with each other, consist of two very small premolars (the first almost rudimentary) and three broad molars, constructed generally like those of Camelus. In the lower jaw, the three incisors are long, spatulate, and procumbent; the outer ones are the smallest. Next to these is a curved, suberect canine, followed after an interval by an isolated minute and often deciduous simple conical premolar; then a contiguous series of one premolar and three molars, which differ from those of Camelus in having a small accessory column at the anterior outer edge.

The skull generally resembles that of Camelus, the larger brain-cavity and orbits, and less-developed cranial ridges being due to its smaller size. The nasal bones are shorter and broader, and are joined by the premaxilla.

- cervical 7,

- dorsal 12,

- lumbar 7,

- sacral 4,

- caudal 15 to 20.

The ears are rather long and slightly curved inward, characteristically known as "banana" shaped. There is no dorsal hump. The feet are narrow, the toes being more separated than in the camels, each having a distinct plantar pad. The tail is short, and fibre is long, woolly and soft.

In essential structural characteristics, as well as in general appearance and habits, all the animals of this genus very closely resemble each other, so whether they should be considered as belonging to one, two, or more species is a matter of controversy among naturalists.

The question is complicated by the circumstance of the great majority of individuals that have come under observation being either in a completely or partially domesticated state. Many are also descended from ancestors that have previously been domesticated, a state that tends to produce a certain amount of variation from the original type. The four forms commonly distinguished by the inhabitants of South America are recognized as distinct species, though with difficulties in defining their distinctive characteristics.

These are:

- the llama, Lama glama (Linnaeus);

- the alpaca, Vicugna pacos (Linnaeus);

- the guanaco (from the Quechua huanaco), Lama guanicoe (Müller); and

- the vicuña, Vicugna vicugna (Molina)

The llama and alpaca are only known in the domestic state, and are variable in size and of many colors, being often white, brown, or piebald. Some are grey or black. The guanaco and vicuña are wild. The guanaco is endangered; it has a nearly uniform light-brown color, passing into white below.

The guanaco and vicuña certainly differ from each other: The vicuña is smaller, more slender in its proportions, and has a shorter head than the guanaco.

The vicuña lives in herds on the bleak and elevated parts of the mountain range bordering the region of perpetual snow, amidst rocks and precipices, occurring in various suitable localities throughout Peru, in the southern part of Ecuador, and as far south as the middle of Bolivia. Its manners very much resemble those of the chamois of the European Alps; it is as vigilant, wild, and timid.

Vicuña fiber is extremely delicate and soft, and highly valued for the purposes of weaving, but the quantity that each animal produces is small. Alpacas are primarily descended from wild vicuña ancestors, while domesticated llamas are descended primarily from wild guanaco ancestors, although a considerable amount of hybridization between the two species has occurred.

Differential characteristics between llamas and alpacas include the llama's larger size, longer head, and curved ears. Alpaca fiber is generally more expensive, but not always more valuable. Alpacas tend to have a more consistent color throughout the body. The most apparent visual difference between llamas and camels is that camels have a hump or humps and llamas do not.

Llamas are not ruminants, pseudo-ruminants, or modified ruminants.[22] They do have a complex three-compartment stomach that allows them to digest lower quality, high cellulose foods. The stomach compartments allow for fermentation of tough food stuffs, followed by regurgitation and re-chewing. Ruminants (cows, sheep, goats) have four compartments, whereas llamas have only three stomach compartments: the rumen, omasum, and abomasum.

In addition, the llama (and other camelids) have an extremely long and complex large intestine (colon). The large intestine's role in digestion is to reabsorb water, vitamins and electrolytes from food waste that is passing through it. The length of the llama's colon allows it to survive on much less water than other animals. This is a major advantage in arid climates where they live.[23]

| لاما Llama | |

|---|---|

| |

| لاما يطل على ماتشو پيتشو، الپيرو | |

Domesticated

| |

| التصنيف العلمي | |

| مملكة: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | L. glama

|

| Binomial name | |

| Lama glama (لينايوس, 1758)

| |

اللاما Llama (اسمه العلمي Lama glama) هو حيوان من العائلة الجمليات Camelid يعيش في جبال الأنديز في أمريكا الجنوبية ويشبه كلاً من الغزال والجمل. ويستخدم لحمل المتاع كما يستخدم السكان وبره ولحمه.[24]

الخصائص

لا يعلم الكثيرون أن اللاما ليس لها رموش. إلا أن ابنة عمها ألپاكا لها رموش.

التكاثر

اللاما لها دورة تكاثر غير معتادة للحيوانات الكبيرة. أنثى اللاما تطلق بويضة بالحث. من خلال عملية الجماع، تطلق الأنثى بويضة وغالباً ما تـُخصـّّب من أول محاولة. أنثى اللاما لا تمر بفترة "شبق" وليس لها دورة حيض estrus.[25]

الحمل

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

التغذية

| وزن الجسم (رطل) |

Bromgrass | ألفا ألفا | Corn Silage | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (كما تؤكل) | (مادة جافة) | (كما تؤكل) | (مادة جافة) | (كما تؤكل) | (مادة جافة) | |

| 22 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 0.4 |

| 44 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 2.6 | 0.7 |

| 88 | 2.1 | 1.9 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 4.3 | 1.2 |

| 110 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 5.2 | 1.4 |

| 165 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 6.9 | 1.9 |

| 275 | 5.0 | 4.5 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 10.1 | 2.8 |

| 385 | 6.4 | 5.7 | 4.3 | 3.9 | 12.9 | 3.6 |

| 495 | 7.8 | 7.0 | 5.3 | 4.8 | 15.8 | 4.4 |

| 550 | 8.5 | 7.6 | 5.7 | 5.2 | 17.0 | 4.8 |

السلوك

كحيوان حراسة

التاريخ

وبر أو ألياف اللاما

| الحيوان | قطر الألياف (ميكرومتر) |

|---|---|

| ڤيكونيا | 6 – 10 |

| الپاكا (Suri) | 10 - 15 |

| Muskox (Qivlut) | 11 - 13 |

| مرينو | 12 - 20 |

| أرنب أنگورا | 13 |

| كاشمير | 15 - 19 |

| وبر الياك | 15 - 19 |

| وبر الجمل | 16 - 25 |

| گواناكو | 16 - 18 |

| لاما (تاپادا) | 20 - 30 |

| چينچيلا | 21 |

| موهير | 25 - 45 |

| ألپاكا (هواكايا) | 27.7 |

| Llama (Ccara) | 30 - 40 |

Technically the fiber is not wool as it is hollow with a structure of diagonal 'walls' which makes it strong, light and good insulation. Wool as a word by itself refers to sheep fiber. However, llama fiber is commonly referred to as llama wool or llama fiber.

انظر أيضاً

- كاما, هجين بين اللاما والجمل]].

- الاما حارس, تستخدم اللاما في حراسة الماشية.

- Lamoid

المصادر

- تحوي هذه المقالة معلومات مترجمة من الطبعة الحادية عشرة لدائرة المعارف البريطانية لسنة 1911 وهي الآن من ضمن الملكية العامةarticle "Llama".

- ^ Daniel W. Gade, Nature and culture in the Andes, Madison, University of Wisconsin Press, 1999, p. 104

- ^ Eveline. "Is Alpaca Wool Hypoallergenic? (Lanolin Free)". Yanantin Alpaca (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 2021-10-16.

- ^ أ ب "Llama". Oklahoma State University. 25 June 2007.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd edition, "llama"

- ^ South Central Llama Association (22 January 2009). "Llama Facts 2".

- ^ أ ب Montecino Aguirre, Sonia (2015). "Llamas". Mitos de Chile: Enciclopedia de seres, apariciones y encantos (in الإسبانية). Catalonia. p. 415. ISBN 978-956-324-375-8.

- ^ Perry, Roger (1977). Wonders of Llamas. Dodd, Mead & Company. p. 7. ISBN 0-396-07460-X.

- ^ Murray E. Fowler (1998). Medicine and Surgery of South American Camelids. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 1. ISBN 0-8138-0397-7.

- ^ "Lama". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- ^ Wheeler, Dr Jane; Miranda Kadwell; Matilde Fernandez; Helen F. Stanley; Ricardo Baldi; Raul Rosadio; Michael W. Bruford (December 2001). "Genetic analysis reveals the wild ancestors of the llama and the alpaca". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 268 (1485): 2575–2584. doi:10.1098/rspb.2001.1774. PMC 1088918. PMID 11749713. 0962-8452 (Paper) 1471–2954 (Online).

- ^ "Mixson's Bone Bed". Florida Museum. September 30, 2013. Retrieved March 26, 2024.

- ^ "The Camels". U.S. National Park Service. October 12, 2021. Retrieved March 26, 2024.

- ^ Kurtén, Björn; Anderson, Elaine (1980). Pleistocene Mammals of North America. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 307. ISBN 0231037333.

- ^ Prothero, Donald R (April 16, 2009). "Evolutionary Transitions in the Fossil Record of Terrestrial Hoofed Mammals". Evolution: Education and Outreach. 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG. Part of Springer Nature. 2 (2): 289–302. doi:10.1007/s12052-009-0136-1. S2CID 32344744.

- ^ Grayson, Donald K. (1991). "Late Pleistocene mammalian extinctions in North America: Taxonomy, chronology, and explanations". Journal of World Prehistory. Springer Netherlands. 5 (3): 193–231. doi:10.1007/BF00974990. S2CID 162363534.

- ^ Frequently Asked Questions - Blue Moon Ranch Alpacas

- ^ Frank, Eduardo; Antonini, Marco; Toro, Oscar (2008). South American camelids research. Volume 2. Wageningen, Netherlands: Wageningen Academic Publishers. ISBN 978-90-8686-648-9. OCLC 846966060.

- ^ "Llama characteristics". Nose-n-Toes. 25 June 2007.

- ^ "Llama facts 1". Llamas of Atlanta. 25 June 2007. Archived from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 5 August 2014.

- ^ "Llama FAQ". Twin Creeks Llamas. 25 June 2007.

- ^ "Dental anatomy of llamas". www.vivo.colostate.edu. Colorado State University.

- ^ Fowler, Murray E. (1 October 2016). "Camelids are not ruminants". Verterian Key (Veterinary Medicine Insight Engine). Chapter 46. Retrieved 2021-05-29.

- ^ Amsel, Sheri (13 November 2017). "Llama thoracic and abdominal organs (right view)". Exploring Nature.

- ^

"Information Resources on the South American Camelids: Llamas, Alpacas, Guanacos, and Vicunas 1943-2006". 2007-06-25.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Greta Stamberg and Derek Wilson (2007-04-12). "Induced Ovulation". Llamapaedia.

- ^ Murray E. Fowler, DVM (1989). "Medicine and Surgery of South American Camelids; Llama, Alpaca, Vicuña, Guanaco". Iowa State University Press.

- ^ Beula Williams (2007-04-17). "Llama Fiber". International Llama Association.

وصلات خارجية

- Queso Cabeza Farm Llama Info - Llama information page. Commercial site but information is comprehensive and useful

- Llamas: From the Andes to the Rockies - Llama information page.

- "Llamapaedia Orgle Sound" (AIFF).

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- CS1 الإسبانية-language sources (es)

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Domesticated animals

- Automatic taxobox cleanup

- Articles with unsourced statements from January 2009

- كل المقالات بدون مراجع موثوقة

- كل المقالات بدون مراجع موثوقة from December 2019

- مقالات مأخوذة من الطبعة الحادية عشرة لدائرة المعارف البريطانية

- صفحات بالمعرفة فيها قوالب حماية خاطئة

- Semi-protected against vandalism

- جمليات

- حيوانات تنتج الشعر

- ماشية

- Quechua loanwords

- ثدييات الأرجنتين

- ثدييات بوليفيا

- ثدييات تشيلي

- ثدييات الإكوادور

- ثدييات بيرو

- حيوانات ضخمة