خطب كاتيلين

خطب كاتيلين (لاتينية: M. Tullii Ciceronis Orationes in Catilinam، Catilinarian Orations)، هي مجموعة من الخطب الموجهة إلى مجلس الشيوخ الروماني التي ألقاها عام 63 ق.م. شيشرون، أحد قناصل ذلك العام، والذي اتهم فيها أحد أعضاء مجلس الشيوخ، لوسيوس سرگيوس كاتيلين (كاتيلين)، الذي قاد مؤامرة للإطاحة بمجلس الشيوخ الروماني. معظم روايات الأحداث تأتي من شيشرون نفسه. يشير بعض المؤرخين المعاصرين، والمصادر القديمة مثل سالوست، إلى أن كاتيلين كان شخصية أكثر تعقيدًا مما تعلنه كتابات شيشرون، وأن شيشرون تأثر بشدة بالرغبة في ترسيخ سمعة دائمة باعتباره وطنيًا ورجل دولة رومانيًا عظيمًا.[1] يعد هذا واحدًا من أفضل الأحداث الموثقة الباقية من العالم القديم، وقد مهد الطريق لصراعات سياسية كلاسيكية تضع أمن الدولة في مواجهة الحريات المدنية.[2]

خلفية

Running for the consulship for a second time after having lost at the first attempt, Catiline was an advocate for the cancellation of debts and for land redistribution. There was apparently substantial evidence that he had bribed numerous senators to vote for him and engaged in other unethical conduct related to the election (such behaviour was, however, hardly unknown in the late Republic). Cicero, in indignation, issued a law prohibiting such machinations,[3] and it seemed obvious to all that the law was directed at Catiline. Catiline, therefore, so Cicero claimed, conspired to murder Cicero and other key senators on the day of the election, in what became known as the Second Catilinarian conspiracy. Cicero announced that he had discovered the plan, and postponed the election to give the Senate time to discuss this supposed coup d'état.

The day after that originally scheduled for the election, Cicero addressed the Senate on the matter, and Catiline's reaction was immediate and violent. In response to Catiline's behavior, the Senate issued a senatus consultum ultimum, a declaration of martial law. Ordinary law was suspended, and Cicero, as consul, was invested with absolute power.

When the election was finally held, Catiline lost again. Anticipating the bad news, the conspirators had already begun to assemble an army, made up mostly of Lucius Cornelius Sulla's veteran soldiers. The nucleus of conspirators was also joined by some senators. The plan was to initiate an insurrection in all of Italy, put Rome to the torch and, according to Cicero, kill as many senators as they could.[4][5]

Through his own investigations, he was aware of the conspiracy. On November 8, Cicero called for a meeting of the Senate in the Temple of Jupiter Stator, near the forum, which was used for that purpose only when great danger was imminent. Catiline attended as well. It was then that Cicero delivered one of his most famous orations.

الخطبة الأولى

As political orations go, it was relatively short, some 3,400 words, and to the point. The opening remarks, brilliantly crafted,[6] are still widely remembered and used after 2000 years:

Quō ūsque tandem abūtere, Catilīna, patientiā nostrā? Quam diū etiam furor iste tuus nōs ēlūdet? Quem ad fīnem sēsē effrēnāta iactābit audācia? |

When, O Catiline, do you mean to cease abusing our patience? How long is that madness of yours still to mock us? When is there to be an end of that unbridled audacity of yours, swaggering about as it does now?[7] |

Also remembered is the famous exasperated exclamation, O tempora, o mores! (Oh, what times! Oh, what behaviour!). Catiline was present when the speech was delivered. He replied to it by asking people not to trust Cicero because he was a self-made man with no family tradition of public office, and to trust himself because of the long experience of his family. Initially, Cicero's words proved unpersuasive.[8] Catiline then ran from the building, hurling threats at the Senate.[citation needed] Later he left the city and claimed that he was placing himself in self-imposed exile at Marseille, but really went to the camp of Manlius, who was in charge of the army of rebels. The next morning Cicero assembled the people, and gave a further oration.

The Second Oration – Oratio in Catilinam Secunda Habita ad Populum

Cicero informed the citizens of Rome that Catiline had left the city not into exile, as Catiline had said, but to join with his illegal army. He described the conspirators as rich men who were in debt, men eager for power and wealth, Sulla's veterans, ruined men who hoped for any change, criminals, profligates and other men of Catiline's ilk. He assured the people of Rome that they had nothing to fear because he, as consul, and the gods would protect the state. This speech was delivered with the intention of convincing the lower class, or common man, that Catiline would not represent their interests and they should not support him.[5]

Meanwhile, Catiline joined up with Gaius Manlius, commander of the rebel force. When the Senate was informed of the developments, they declared the two of them public enemies. Antonius Hybrida (Cicero's fellow consul), with troops loyal to Rome, followed Catiline while Cicero remained at home to guard the city.

الخطبة الثالثة

Cicero claimed that the city should rejoice because it had been saved from a bloody rebellion. He presented evidence that all of Catiline's accomplices confessed to their crimes. He asked for nothing for himself but the grateful remembrance of the city and acknowledged that the victory was more difficult than one in foreign lands because the enemies were citizens of Rome.

الخطبة الرابعة

In his fourth and final published[9] argument, which took place in the Temple of Concordia, Cicero establishes a basis for other orators (primarily Cato the Younger) to argue for the execution of the conspirators. As consul, Cicero was formally not allowed to voice any opinion in the matter, but he circumvented the rule with subtle oratory. Although very little is known about the actual debate (except for Cicero's argument, which has probably been altered from its original), the Senate majority probably opposed the death sentence for various reasons, one of which was the nobility of the accused. For example, Julius Caesar argued that exile and disenfranchisement would be sufficient punishment for the conspirators, and one of the accused, Lentulus, was a praetor. However, after the combined efforts of Cicero and Cato, the vote shifted in favor of execution, and the sentence was carried out shortly afterwards.

While some historians[محل شك] agree that Cicero's actions, in particular the final speeches before the Senate, may have saved the Republic, they also reflect his self-aggrandisement and, to a certain extent envy, probably born out of the fact that he was considered a novus homo, a Roman citizen without noble or ancient lineage.[10]

الترجمات

Cicero's Orations by Marcus Tullius Cicero', available at Project Gutenberg.

- At Perseus Project (Latin text, translation and analysis):

- Yonge, C.D., ed. (1856). The Orations of Marcus Tullius Cicero. London: Henry G. Bohn – via Perseus Digital Library.:

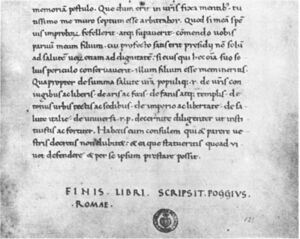

- Clark, Albert Curtis, ed. (1908). M. Tulli Ciceronis Orationes (in اللاتينية). Scriptorum Classicorum Bibliotheca Oxoniensis – via Perseus Digital Library.

الهوامش

المصادر

- ^ Hoffman, Richard (1998). "Sallust and Catiline". The Classical Review. 48 (1): 50–52. doi:10.1017/S0009840X00330335. JSTOR 713695. S2CID 162587795.

- ^ Beard, Mary (2015). SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome. New York: Liveright. pp. 21–53. ISBN 9780871404237.

- ^ Dio Cassius XXXVII.29.1

- ^ Cicero, Marcus Tullius (2014). Delphi Complete Works of Cicero (Illustrated). online: Delphi Classics.

- ^ أ ب "The Conspiracy of Catiline (63 B.C.)". www.thelatinlibrary.com. Retrieved 2017-03-04.

- ^ Krebs, C.B. (2020). "Painting Cariline into a Corner: Form and Content in Cicero's in Catilinam 1.1". Classical Quarterly. 70 (2): 672–676. doi:10.1017/S0009838820000762. S2CID 230578487. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ Cicero, Marcus Tullius. "Against Catiline". Trans. Charles Duke Young. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ^ Wasson, Donald L. (3 February 2016). "Cicero & the Catiline Conspiracy". World History Encyclopedia.

- ^ M. Tullius Cicero. Evelyn Shuckburgh; Evelyn S. Shuckburgh (eds.). "Cic. Att. 2.1". Letters to Atticus.

- ^ Robert W. Cape, Jr.: "The rhetoric of politics in Cicero's fourth Catilinarian", American Journal of Philology, 1995

المراجع

- Berry, DH (2020). Cicero's Catilinarians. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-751081-0. LCCN 2019048911. OCLC 1126348418.