مرينو

مـِرينو Merino هو أحد أشهر أشهر سلالات الخراف تاريخياً وأكثرها تأثيراً من الناحية الاقتصادية، يشتد عليها الطلب لصوفها. تنحدر السلالة من إكستريمادورا، في جنوب غرب اسبانيا، حوالي القرن الثاني عشر؛ وكانت أساسية في التنمية الاقتصادية في اسبانيا القرنين الخامس عشر والسادس عشر، التي احتكرت تجارته، ومنذ نهاية القرن الثامن عشر فقد تحسنت السلالة في نيوزيلندا وأستراليا، ببروز المرينو المعاصر.

واليوم، مازال المرينو يُعتبر صاحب أدق وأنعم صوف لأي خروف. مرينو پول لا قرون لهم (أو لهم منابت قرون ضئيلة)، أما المرينو ذوي القرون، فقرونهم طويلة وملتوية وتنمو قريبة من الرأس.[1]

أصل الاسم

Two suggested origins for the Spanish word merino are:[2]

- It may be an adaptation to the sheep of the name of a Leonese official inspector (merino) over a merindad, who may have also inspected sheep pastures. This word is from the medieval Latin maiorinus, a steward or head official of a village, from maior, meaning "greater".

- It also may be from the name of an Imazighen tribe, the Marini (or in Spanish, Benimerines), who intervened in the Iberian peninsula during the 12th and 13th centuries.(see Prosper Ricard in "Guide Bleu")

السمات

The Merino is an excellent forager and very adaptable. It is bred predominantly for its wool,[3] and its carcass size is generally smaller than that of sheep bred for meat. South African Meat Merino (SAMM), American Rambouillet and German Merinofleischschaf[4] have been bred to balance wool production and carcass quality.

Merino have been domesticated and bred in ways that would not allow them to survive well without regular shearing by their owners. They must be shorn at least once a year because their wool does not stop growing. If this is neglected, the overabundance of wool can cause heat stress, mobility issues, and even blindness.[5]

جودة الصوف

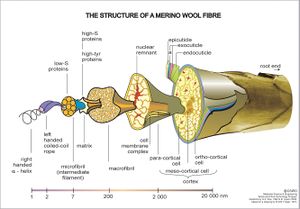

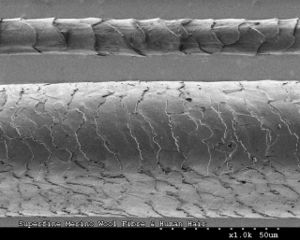

Merino wool is fine and soft. Staples are commonly 65–100 mm (2.6–3.9 in) long. A Saxon Merino produces 3–6 kg (6.6–13.2 lb) of greasy wool a year, while a good quality Peppin Merino ram produces up to 18 kg (40 lb). Merino wool is generally less than 24 micron (μm) in diameter. Basic Merino types include: strong (broad) wool (23–24.5 μm), medium wool (19.6–22.9 μm), fine (18.6–19.5 μm), superfine (15–18.5 μm) and ultra fine (11.5–15 μm).[6] Ultra fine wool is suitable for blending with other fibers such as silk and cashmere.

The term merino is widely used in the textile industries, but it cannot be taken to mean the fabric in question is actually 100% merino wool from a Merino strain bred specifically for its wool. The wool of any Merino sheep, whether reared in Spain or elsewhere, is known as "merino wool". However, not all merino sheep produce wool suitable for clothing, and especially for clothing worn next to the skin or as a second skin. This depends on the particular strain of the breed. Merino sheep bred for meat do not produce a fleece with a fine enough staple for this purpose.

تاريخ

جلب الفينيقيون الخراف من آسيا الصغرى إلى شمال أفريقيا and the foundation flocks of the merino in Spain might have been introduced as late as the 12th century by the Marinids, a tribe of Berbers.[citation needed] although there were reports of the breed in the Iberian peninsula before the arrival of the Marinids; perhaps these came from the Merinos or tax collectors of the Kingdom of León, who charged the tenth in wool, beef jerky and cheese.[citation needed] In the 13th and 14th centuries, Spanish breeders introduced English breeds which they bred with local breeds to develop the merino; this influence was openly documented by Spanish writers at the time.[7]

Spain became noted for its fine wool (spinning count between 60s and 64s) and built up a fine wool monopoly between the 12th and 16th centuries, with wool commerce to Flanders and England being a source of income for Castile in the Late Middle Ages.

Most of the flocks were owned by nobility or the church; the sheep grazed the Spanish southern plains in winter and the northern highlands in summer. The Mesta was an organisation of privileged sheep owners who developed the breed and controlled the migrations along cañadas reales suitable for grazing.

The three Merino strains that founded the world's Merino flocks are the Royal Escurial flocks, the Negretti and the Paula. Among Merino bloodlines stemming from Vermont in the USA, three historical studs were highly important: Infantado, Montarcos and Aguires.

المرينو الأسترالي

التاريخ المبكر

About 70 native sheep, suitable only for mutton, survived the journey to Australia with the First Fleet, which arrived in late January 1788. A few months later, the flock had dwindled to just 28 ewes and one lamb.[8]

In 1797, Governor King, Colonel Patterson, Captain Waterhouse and Kent purchased sheep in Cape Town from the widow of Colonel Gordon, commander of the Dutch garrison. When Waterhouse landed in Sydney, he sold his sheep to Captain John MacArthur, Samuel Marsden and Captain William Cox.[9]

جون وإلزابث مكارثر

By 1810, Australia had 33,818 sheep.[10] John MacArthur (who had been sent back from Australia to England following a duel with Colonel Patterson) brought seven rams and one ewe from the first dispersal sale of King George III stud in 1804. The next year, MacArthur and the sheep returned to Australia, Macarthur to reunite with his wife Elizabeth, who had been developing their flock in his absence. Macarthur is considered the father of the Australian Merino industry; in the long term, however, his sheep had very little influence on the development of the Australian Merino.

Macarthur pioneered the introduction of Saxon Merinos with importation from the Electoral flock in 1812. The first Australian wool boom occurred in 1813, when the Great Dividing Range was crossed. During the 1820s, interest in Merino sheep increased. MacArthur showed and sold 39 rams in October 1820, grossing £510/16/5.[11] In 1823, at the first sheep show held in Australia, a gold medal was awarded to W. Riley ('Raby') for importing the most Saxons; W. Riley also imported cashmere goats into Australia.

إلايزا وجون فرلونگ

Two of Eliza Furlong's (sometimes spelt Forlong or Forlonge) children had died from consumption, and she was determined to protect her surviving two sons by living in a warm climate and finding them outdoor occupations. Her husband John, a Scottish businessman, had noticed wool from the Electorate of Saxony sold for much higher prices than wools from NSW. The family decided on sheep farming in Australia for their new business. In 1826, Eliza walked over 1،500 ميل (2،400 km) through villages in Saxony and Prussia, selecting fine Saxon Merino sheep. Her sons, Andrew and William, studied sheep breeding and wool classing. The selected 100 sheep were driven (herded) to Hamburg and shipped to Hull. Thence, Eliza and her two sons walked them to Scotland for shipment to Australia. In Scotland, the new Australia Company, which was established in Britain, bought the first shipment, so Eliza repeated the journey twice more. Each time, she gathered a flock for her sons. The sons were sent to NSW, but were persuaded to stop in Tasmania with the sheep, where Eliza and her husband joined them.[12]

The Melbourne Age in 1908 described Eliza Furlong as someone who had 'notably stimulated and largely helped to mould the prosperity of an entire state and her name deserved to live for all time in our history' (reprinted Wagga Wagga Daily Advertiser January 27, 1989).[13]

الوضع الحالي

In Australia today, a few Saxon and other fine-wool, German bloodline, Merino studs exist in the high rainfall areas.[14] In the pastoral and agriculture country, Peppins and Collinsville (21 to 24 micron) are popular.

In the drier areas, one finds the Collinsville (21 to 24 micron) strains. The development of the Merino is entering a new phase: objective fleece measurement and BLUP is now being used to identify exceptional animals. Artificial insemination and embryo transfer are being used to accelerate the spread of their genes. The result is a wide outcrossing between all major strains.[citation needed]

أعلى أسعار قياسية

The world record price for a ram was A$450,000 for JC&S Lustre 53, which sold at the 1988 Merino ram sale at Adelaide, South Australia.[15] In 2008, an Australian Merino ewe was sold for A$14,000 at the Sheep Show and auction held at Dubbo, New South Wales.[16]

تطورات الرفق بالحيوان

In Australia, mulesing of Merino sheep is a common practice to reduce the incidence of flystrike. It has been attacked by animal rights and animal welfare activists, with PETA running a campaign against the practice in 2004. The PETA campaign targeted U.S. consumers by using graphic billboards in New York City. PETA threatened U.S. manufacturers with television advertisements showing their companies' support of mulesing. Fashion retailers including Abercrombie & Fitch Co., Gap Inc and Nordstrom and George (UK) stopped stocking Australian Merino wool products.[17]

Several European clothing retailers, including H&M, stopped stocking products made with Merino wool from Australia.[18]

New strains of Merinos that do not require mulesing are being promoted in South Australia.[19] 'Thin-skinned' sheep from western Victoria are also being promoted as a solution.

انظر أيضاً

- Arkhar-Merino, a crossbreed with wild Urials

- Booroola Merino, prolific Merino strain

- Delaine Merino

- Peppin Merino, dominant Australian Merino strain

- Poll Merino

- Rambouillet (sheep)

- Lepau Merino

- Chris, an Australian Merino sheep who was sheared of a record amount of wool

المراجع

- ^ "Merino wool". Oviedo, Florida: NuMei. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- ^ Corominas, Joan; Pascual, José A., eds. (1989). "Merino". Diccionario Crítico Etimológico Castellano e Hispánico. Vol. IV. Madrid: Gredos. ISBN 84-249-0066-9.

- ^ The Macquarie Dictionary. North Ryde: Macquarie Library. 1991.

- ^ "Breeds of Livestock - German Mutton Merino Sheep". Ansi.okstate.edu. 1998-12-10. Archived from the original on 2012-09-14. Retrieved 2012-08-20.

- ^ Will a Sheep's Wool Grow Forever?, http://modernfarmer.com/2013/07/will-sheep/

- ^ Australian Wool Classing, Australian Wool Corporation, 1990, p. 26

- ^ "Wool". The New American Cyclopaedia. Vol. 16. D. Appleton and Company. 1858. p. 538.

- ^ McCosker, Malcolm, Heritage Merino, Owen Edwards Publications, West End, 1988 ISBN 0-9588612-3-4

- ^ Lewis, Wendy, Simon Balderstone and John Bowan (2006). Events That Shaped Australia. New Holland. ISBN 978-1-74110-492-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ The Edinburgh Gazetteer, volume 1, Archibald Constable and Co.: Edinburgh, 1822, p.570

- ^ The Australian Merino, Charles Massey, Viking O'Neil, South Yarra, 1990, p.62

- ^ ADB: Forlong, Eliza (1784 - 1859) Retrieved 2009-11-28

- ^ Mary S. Ramsay, 'Forlong, Eliza (1784 - 1859)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, Supplementary Volume, Melbourne University Press, 2005, pp 130-131.

- ^ The Australian Merino, Charles Massey, Viking O'Neil, South Yarra, 1990, p. 405

- ^ Stock and Land Retrieved on 2008-9-8

- ^ The Land, Rural Press, North Richmond, NSW, 4 September 2008

- ^ "Abercrombie & Fitch Pledges Not to Use Australian Merino Wool Until Mulesing and Live Exports End". PETA.org. Retrieved 2012-08-20.

- ^ "H&M Stops Selling Australian Wool | Ethisphere Institute". Ethisphere.com. 2008-02-19. Archived from the original on 2012-03-29. Retrieved 2012-08-20.

- ^ "Scientists search for bare-bum sheep gene". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 21 March 2005. Retrieved 2007-11-25.

للاستزادة

- Cottle, D.J. (1991). Australian Sheep and Wool Handbook. Melbourne, Australia: Inkata Press. pp. 20–23. ISBN 0-909605-60-2.