جولاج

| جزء من سلسلة عن |

| الاتحاد السوڤيتي |

|---|

گولاگ Gulag (روسية: ГУЛаг, النطق GULag; النطق الروسي: [ɡʊˈlak] (![]() استمع))، هي وكالة حكومية تشرف مباشرة على أنظمة معسكرات العمل القسري السوڤيتية.[1] بينما كانت تضم تلك المعسكرات أعداد متبانية من المدانين، صغار المعتقلين السياسييين، أعداد كبيرة من المدانين بالجنايات الصغرى.

استمع))، هي وكالة حكومية تشرف مباشرة على أنظمة معسكرات العمل القسري السوڤيتية.[1] بينما كانت تضم تلك المعسكرات أعداد متبانية من المدانين، صغار المعتقلين السياسييين، أعداد كبيرة من المدانين بالجنايات الصغرى.

ألكسندر سولجنيتسين، الفائز بجائزة نوبل للأدب 1970، قدم مصطلح الگولاگ إلى الغرب في كتاب أرخبيل الگولاگ عام 1973.

تعبير الگولاگ استخدمته أيضا الأمين العام لمنظمة العفو الدولية ايرين خان، وهى تعرض تقرير المنظمة لعام 2005، فقد وصفت معسكر الاعتقال الأمريكي في گوانتانامو بأنه گولاگ العصر الذي يكرس ممارسات الاعتقال التعسفي لفترات غير محددة في انتهاك للقانون الدولي.[2]

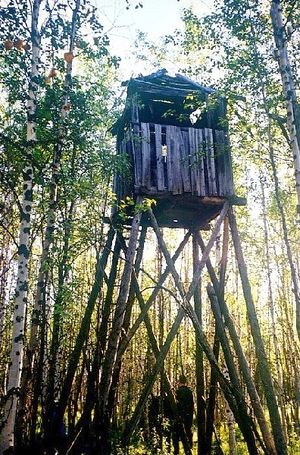

في مارس 1940، كان يوجد 53 مخيم منفصل و423 مستعمرة عمل في الاتحاد السوڤيتي.[3] المدن الصناعية الكبرى في منطقة القطب الشمالي الروسي، مثل نوريسلك، ڤوركوتا، وماگادان، كانت في الأصل مخيمات بناها وعمرها السجناء.[4]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

تاريخ موجز

يرجع تاريخ الگولاگ إلى عام 1918، أى بعد عام واحد من قيام الثورة البلشفية التى فجرها لينين. ولكنه صار من معالم عصر ستالين الدموي. كان الگولاگ في عهده عبارة عن معسكرات للعمل الإلزامي والسخرة، تعرض المقيمون بها لكل أشكال القمع والتنكيل. كان معقلا لانتهاك كل حقوق الإنسان.

ويقال أن ضحايا الگولاگ السوڤيتي في عهد ستالين منذ عام 1929 إلى 1953 حوالي 18 مليون سوڤيتي، سقط منهم قرابة خمسة ملايين شخص.

التاريخ

التأسيس والتوسيع في عهد ستالين

تأسس الگولاگ رسمياً في 25 أبريل 1930، وفقاً لأمر سوڤناركوم رقم 22 p. 248 الصادر في 2 أبريل 1930. وسمي بالگولاگ في نوفمبر من العام نفسه.[7]

أثناء الحرب العالمية الثانية

| القمع في الإتحاد السوڤيتي |

|---|

| عام |

| القمع السياسي • القمع الاقتصادي • القمع الأيديولوجي |

| قمع سياسي |

| الإرهاب الأحمر • Collectivization • Great Purge • نقل السكان • گولاگ • Holodomor • القتل العشوائي • Political abuse of psychiatry |

|

Ideological repression |

| الدين • أبحاث • الرقابة • الرقابة على الصور |

بعد الحرب العالمية الثانية

بعد الحرب العالمية الثانية، ارتفع عدد المعتقلون والسجان في مخيمات الگولاگ مرة أخرى، ليصل إلى حوالي 2.5 مليون شخص في أوائل الخمسينيات (كان في المخيمات حوالي 1.7 مليون).

| نتيجة الانتقاء والاختيار بين العائدين للمخيمات (في 1 مارس 1946)[8] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| التصنيف | الإجمالي | % | المدنية | % | الأسرى | % | |

| أفرج عنهم وعادوا لمنازلهم (يشمل هذا الرقم الأشخاص المتوفون في السجن) | 2,427,906 | 57.81 | 2,146,126 | 80.68 | 281,780 | 18.31 | |

| جندوا | 801,152 | 19.08 | 141,962 | 5.34 | 659,190 | 42.82 | |

| أرسلوا لكتائب العمل في وزارة الدفاع | 608,095 | 14.48 | 263,647 | 9.91 | 344,448 | 22.37 | |

| أرسلوا إلى NKVD as spetskontingent(مثل الگولاگ) | 272,867 | 6.50 | 46,740 | 1.76 | 226,127 | 14.69 | |

| في انتظار النقل أو العمل في وحدات العسكرية السوڤيتية بالخارج | 89,468 | 2.13 | 61,538 | 2.31 | 27,930 | 1,81 | |

| الإجمالي: | 4,199,488 | 2,660,013 | 1,539,475 |

(انظر أيضاً Foreign forced labor in the Soviet Union)

الجغرافيا

التأريخ

احصائيات تاريخية لمعسكرات الگولاگ

| سكان الگولاگ | سنة الاحصاء | المصدر | المنهجية | ||

| 15 مليون | 1940-42 | Mora & Zwiernag(1945)[9] | -- | ||

| 2.3 مليون | ديسمبر 1937 | Timasheff(1948)[10] | Calculation of disenfranchised population | ||

| أكثر من 3.5 مليون | 1941 | Jasny(1951)[11] | Analysis of the output of the Soviet enterprises run by NKVD | ||

| 50 مليون | total number of persons passed through GULAG |

Solzhenitsyn(1975)[12] | Analysis of various indirect data, including own experience and testimonies of numerous witnesses | ||

| 16 مليون | 1938 | Antonov-Ovseenko(1980)[13] | -- | ||

| 4-5 مليون | 1939 | Wheatcroft(1981)[14] | Analysis of demographic data.[2] | ||

| 10.6 مليون | 1941 | Rosefielde(1981)[15] | Based on data of Mora & Zwiernak and annual mortality.[3] | ||

| 5.5-9.5 مليون | أواخر 1938 | Conquest (1991)[16] | 1937 Census figures, arrest and deaths estimates, variety of personal and literary sources.[4] | ||

| 4-5 مليون | كل سنة مفردة | Volkogonov (1990s)[17] | |||

| a.^ هوامش: Later numbers from Rosefielde, Wheatcroft and Conquest were revised down by the authors themselves.[18][19] | |||||

التأثير

الثقافة

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الأدب

تم نشر العديد من روايات شهداء العيان عن معتقلات الگولاگ:

- Varlam Shalamov's Kolyma Tales is a short-story collection, cited by most major works on the Gulag, and widely considered one of the main Soviet accounts.

- Victor Kravchenko wrote "I Chose Freedom" after defecting to the الولايات المتحدة in 1944. As a leader of industrial plants he had encountered forced labor camps in various parts of the Soviet Union from 1935 to 1941. He describes a visit to one camp at Kemerovo on river Tom in Siberia. Factories paid a fixed sum to the KGB for every convict they employed.

- Anatoli Granovsky wrote "I Was an NKVD Agent" after defecting to Sweden in 1946 and included his experiences seeing gulag prisoners as a young boy, as well as his experiences as a prisoner himself in 1939. Granovsky's father was sent to the gulag in 1937.

- Julius Margolin's book A Travel to the Land Ze-Ka was finished in 1947, but it was impossible to publish such a book about the Soviet Union at the time, immediately after World War II.

- Gustaw Herling-Grudziński wrote A World Apart, which was translated into English by Andrzej Ciolkosz and published with an introduction by Bertrand Russell in 1951. By describing life in the gulag in a harrowing personal account, it provides an in-depth, original analysis of the nature of the Soviet communist system.

- Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's book The Gulag Archipelago was not the first literary work about labor camps. His previous book on the subject, "One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich", about a typical day of the Gulag inmate, was originally published in the most prestigious Soviet monthly, Novy Mir, (New World), in November 1962, but was soon banned and withdrawn from all libraries. It was the first work to demonstrate the Gulag as an instrument of governmental repression against its own citizens on a massive scale. The First Circle, an account of three days in the lives of prisoners in the Marfino sharashka or special prison was submitted for publication to the Soviet authorities shortly after One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich but was rejected and later published abroad in 1968.

- János Rózsás, Hungarian writer, often referred to as the Hungarian Solzhenitsyn, wrote a lot of books and articles on the issue of GULag.

- Zoltan Szalkai, Hungarian documentary filmmaker made several films of gulag camps.

- Karlo Štajner, a Croatian communist active in the former Kingdom of Yugoslavia and manager of Comintern Publishing House in Moscow from 1932–39, was arrested one night and taken from his Moscow home under accusation of anti-revolutionary activities. He spent the following 20 years in camps from Solovki to Norilsk. After USSR–Yugoslavian political normalization he was re-tried and quickly found innocent. He left the Soviet Union with his wife, who had been waiting for him for 20 years, in 1956 and spent the rest of his life in Zagreb, Croatia. He wrote an impressive book entitled 7000 days in Siberia.

- Dancing Under the Red Star by Karl Tobien (ISBN 1-4000-7078-3) tells the story of Margaret Werner, a young athletic girl who moves to Russia right before the start of Stalin's terror. She faces many hardships, as her father is taken away from her and imprisoned. Werner is the only American woman who survived the Gulag to tell about it.

- "Alexander Dolgun's Story: An American in the Gulag." (ISBN 0-394-49497-0), of a member of the US Embassy, and "I Was a Slave in Russia" (ISBN 0-815-95800-5), an American factory owner's son, were two more American citizens interned who wrote of their ordeal. Both were interned due to their American citizenship for about 8 years c. 1946–55.

- Yevgenia Ginzburg wrote two famous books of her remembrances, Journey Into the Whirlwind and Within the Whirlwind.

- Savić Marković Štedimlija, pro-Croatian Montenegrin ideologist and Ustasha regime collaborator. Caught on the run in Austria by the Red Army in 1945, he was sent to the USSR and spent ten years in Gulag. After release, Marković wrote autobiographic account in two volumes titled Ten years in Gulag (Deset godina u Gulagu, Matica crnogorska, Podgorica, Montenegro 2004)

- Sławomir Rawicz's book, The Long Walk is a controversial account of his escape from the gulag during الحرب العالمية الثانية.

سينما وتلفزيون

الاستعمار

Soviet state documents show that the goals of the gulag included colonisation of sparsely-populated remote areas. To this end, the notion of "free settlement" was introduced.

When well-behaved persons had served the majority of their terms, they could be released for "free settlement" (вольное поселение, volnoye poseleniye) outside the confinement of the camp. They were known as "free settlers" (вольнопоселенцы, volnoposelentsy, not to be confused with the term ссыльнопоселенцы,ssyl'noposelentsy, "exile settlers"). In addition, for persons who served full term, but who were denied the free choice of place of residence, it was recommended to assign them for "free settlement" and give them land in the general vicinity of the place of confinement.

The gulag inherited this approach from the katorga system.

الحياة بعد الإفراج والعمل

نصب تذكارية

يوجد في موسكو وسانت پكرسبورگ نصب تذكاري لضحايا معسكر سولوڤكي - أول معسكرات الگولاگ. النصب التذكاري الأول في ميدان لوبيانكا، موسكو. يجتمع الناس لاحياء ذكرى ضحايا القمع السياسي الموافق 30 أكتوبر من كل عام.

متحف الگولاگ

متحف الگولاگ في موسكو ويديره أنطون أنطونوڤ-اوڤسينكو.[20][21][22]

مشاهير سجناء الگولاگ

- يوسف ڤاسير چامانزامينلي

- والتر سيزك

- نيقولا گتمان

- سرجي كوروليوڤ

- ڤلاديمير پتروڤ

- ڤارلام شالاموڤ

- ألكسندر سولجنيتسين

- كارل ستينر

- نيقولا تيموفيڤ-رسوڤسكي

انظر أيضاً

- 101st kilometre

- Art and culture in the Gulag labor camps

- مقال 58

- مقالات متعلقة بالإتحاد السوڤيتي

- Involuntary settlements in the Soviet Union

- Kengir uprising

- Kolyma

- رسائل من السجناء الروس

- قائمة معسكرات الگولاگ

- قائمة ثورات الگولاگ

- المقابر العشوائية في الإتحاد السوڤيتي

- Memorial

- Nazino affair

- Norilsk uprising, an uprising in Norilsk "Gorlag" (mining camp), 1953

- Persecution of Christians in the Soviet Union

- Population transfer in the Soviet Union

- Punitive psychiatry in the Soviet Union

- مافيا روسية

- القمع السياسي السوڤيتي

- Thief in law

- USSR anti-religious campaign (1928–1941)

×مخيمات العمل القسري في أماكن أخرى:

- Camp 22 (كوريا الشمالية)

- Danube-Black Sea Canal (رومانيا الشيوعية)

- جزيرة الشيطان (فرنسا)

- Extermination through labor (ألمانيا النازية)

- Goli Otok (يوغسلاڤيا)

- Katorga (الإمبراكورية الروسية)

- Laogai (الصين)

- الرق في الولايات المتحدة (الولايات المتحدة)

- الگولاگ الڤيتنامي

- Yodok (كوريا الشمالية)

المصادر

- ^ Other Soviet penal labor systems not included in GULag were: (a) camps for the prisoners of war captured by the الاتحاد السوڤيتي, administered by GUPVI (b) filtration camps created during الحرب العالمية الثانية for temporary detention of Soviet Ostarbeiters and prisoners of war while they were being screened by the security organs in order to "filter out" the black sheep, (c) "special settlements" for internal exiles including "kulaks" and deported ethnic minorities, such as Volga Germans, Poles, Balts, Caucasians, Crimean Tartars, and others. During certain periods of Soviet history, each of them kept millions of people. Many hundreds of thousand were also sentenced to forced labor without imprisonment at their normal place of work (Applebaum, pages 579-580)

- ^ غوانتانامو وأبوغريب.. جولاج من نوع آخر، نادي الفكر العربي

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةGRZ - ^ "Gulag: a History of the Soviet Camps". Arlindo-correia.com. Retrieved 2009-01-06.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ "Демографические потери от репрессий". Demoscope.ru. Retrieved 2011-12-19.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةmemo - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةZemscovRep - ^ Cited in David Dallin and Boris Nicolaevsky, Forced Labor in Soviet Russia. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1947), p. 59-62.

- ^ N. S. Timasheff. The Postwar Population of the Soviet Union. American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 54, No. 2 (Sep., 1948), pp. 148-155

- ^ Naum Jasny. Labor and Output in Soviet Concentration Camps. Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 59, No. 5 (Oct., 1951), pp. 405-419

- ^ Solzhenitsyn, A. The Gulag Archipelago Two, Harper and Row, 1975. Estimate was through 1953.

- ^ Anton Antonov-Ovseenko, Portret tirana (New York: Khronika, 1980), p. 387

- ^ S. G. Wheatcroft. On Assessing the Size of Forced Concentration Camp Labour in the Soviet Union, 1929-56. Soviet Studies, Vol. 33, No. 2 (Apr., 1981), pp. 265-295

- ^ Steven Rosefielde. An Assessment of the Sources and Uses of Gulag Forced Labour 1929-56. Soviet Studies, Vol. 33, No. 1 (Jan., 1981), pp. 51-87

- ^ Robert Conquest. Excess Deaths and Camp Numbers: Some Comments. Soviet Studies, Vol. 43, No. 5 (1991), pp. 949-952

- ^ Rappaport, H. Joseph Stalin: A Biographical Companion. ABC-CLIO Greenwood. 1999.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةConquestGRZ - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةrosenf - ^ Гальперович, Данила (2010). "Директор Государственного музея ГУЛАГа Антон Владимирович Антонов-Овсеенко". Radio Liberty. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Banerji, Arup (2008). Writing history in the Soviet Union: making the past work. Berghahn Books. p. 271. ISBN 8187358378.

- ^ "About State Gulag Museum". The State Gulag Museum. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

قراءات إضافية

- كتب

- Anne Applebaum, Gulag: A History, Broadway Books, 2003, hardcover, 720 pp., ISBN 0-7679-0056-1.

- Walter Ciszek, With God in Russia, Ignatius Press, 1997, 433 pp., ISBN 0-8987-0574-6.

- Simon Ertz, Zwangsarbeit im stalinistischen Lagersystem: Eine Untersuchung der Methoden, Strategien und Ziele ihrer Ausnutzung am Beispiel Norilsk, 1935-1953, Duncker & Humblot, 2006, 273 pp., ISBN 9783428118632.

- Orlando Figes, The Whisperers: Private Life in Stalin's Russia, Allen Lane, 2007, hardcover, 740 pp., ISBN 0141013516.

- J. Arch Getty, Oleg V. Naumov, The Road to Terror: Stalin and the Self-Destruction of the Bolsheviks, 1932-1939, Yale University Press, 1999, 635 pp., ISBN 0-300-07772-6.

- Jehanne M. Gheith and Katherine R. Jolluck. Gulag Voices: Oral Histories of Soviet Detention and Exile (Palgrave Studies in Oral History). Palgrave Macmillan, 2010. ISBN 0230610633

- Slawomir Rawicz. "The Long Walk". 1995. ISBN 1558216847

- Paul R. Gregory, Valery Lazarev, eds, The Economics of Forced Labor: The Soviet Gulag, Stanford: Hoover Institution Press, 2003, ISBN 0-8179-3942-3, full text available online at "Hoover Books Online"

- Jan T. Gross (intro) and Nicolas Werth, Cannibal Island: Death in a Siberian Gulag (Human Rights and Crimes against Humanity). Princeton University Press, 2007. 248 pp., ISBN 0691130833.

- Gustaw Herling-Grudzinski, A World Apart: Imprisonment in a Soviet Labor Camp During World War II, Penguin, 1996, 284 pp., ISBN 0-14-025184-7.

- Adam Hochschild, The Unquiet Ghost: Russians Remember Stalin (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2003), 304 pp., paperback: ISBN 0-618-25747-0.

- Oleg V. Khlevniuk, The History of the Gulag: From Collectivization to the Great Terror, Yale University Press, 2004, hardcover, 464 pp., ISBN 0-300-09284-9.

- Tomasz Kizny, Gulag: Life and Death Inside the Soviet Concentration Camps 1917-1990, Firefly Books Ltd., 2004, 496 pp., ISBN 1-55297-964-4.

- Istorija stalinskogo Gulaga: konec 1920-kh - pervaia polovina 1950-kh godov; sobranie dokumentov v 7 tomach, ed. by V. P. Kozlov et al., Moskva: ROSSPEN 2004-5, 7 vols. ISBN 5-8243-0604-4

- Jacques Rossi, The Gulag Handbook: An Encyclopedia Dictionary of Soviet Penitentiary Institutions and Terms Related to the Forced Labor Camps, 1989, ISBN 1-55778-024-2.

- Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

- The Gulag Archipelago, Harper & Row, 660 pp., ISBN 0-06-080332-0.

- The Gulag Archipelago: Two, Harper & Row, 712 pp., ISBN 0-06-080345-2.

- Karl Tobien. Dancing Under the Red Star: The Extraordinary Story of Margaret Werner, the Only American Woman to Survive Stalin's Gulag. WaterBrook Press, 2006. ISBN 1400070783

- Nicolas Werth, "A State Against Its People: Violence, Repression, and Terror in the Soviet Union, in Stephane Courtois et al., eds., The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression, Harvard University Press, 1999, ISBN 0-674-07608-7, pp. 33–260.

- "The Literature of Stalin's Repressions" in Azerbaijan International, Vol 14:1 (Spring 2006)

- نصب تذكارية

- Ayyub Baghirov (1906-1973), Bitter Days of Kolyma

- Murtuz Sadikhli (1927-1997), Memory of Blood

- Ummugulsum Sadigzade (died 1944), Prison Diary: Tears Are My Only Companions

- Ummugulsum Sadigzade (died 1944), Letters from Prison to her Young Children

- Remembering Stalin - Azerbaijan International 13.4 (Winter 2005)

- Anne Applebaum (foreword) and Paul Hollander (introduction and editor). From the Gulag to the Killing Fields: Personal Accounts of Political Violence and Repression in Communist States. Intercollegiate Studies Institute, 2006. ISBN 1932236783 (from the annotation: "more than forty dramatic personal memoirs of Communist violence and repression from political prisoners across the globe")

- Janusz Bardach, Man Is Wolf to Man: Surviving the Gulag. University of California Press, 1999. ISBN 0520221524

- Alexander Dolgun, Patrick Watson, "Alexander Dolgun's story: An American in the Gulag", NY, Knopf, 1975, 370 pp., ISBN 978-0394494975.

- Eugenia Ginzburg, Journey into the whirlwind, Harvest/HBJ Book, 2002, 432 pp., ISBN 0156027518.

- Eugenia Ginzburg, Within the Whirlwind, Harvest/HBJ Book, 1982, 448 pp., ISBN 0156976498.

- Jerzy Gliksman, Tell the West: An account of his experiences as a slave laborer in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, Gresham Press, 358pp. (abridged edition: New York : National Committee for a Free Europe, c 1948, 95pp.)

- Julius Margolin, ПУТЕШЕСТВИЕ В СТРАНУ ЗЭ-КА A Travel to the Land Ze-Ka, full text, according to the original manuscript (book written in 1947-47, first printed in 1952) (بالروسية)

- Fyodor V. Mochulsky, Gulag Boss: A Soviet Memoir, Oxford University Press, 272 pp., the first memoir from an NKVD employee translated into English

- Tamara Petkevich, Memoir of a Gulag Actress, Northern Illinois University, 2010

- John H. Noble, I Was a Slave in Russia, Broadview, Illinois: Cicero Bible Press, 1961).

- Varlam Shalamov, Kolyma Tales, Penguin Books, 1995, 528 pp., ISBN 0-14-018695-6.

- Danylo Shumuk,

- Life sentence: Memoirs of a Ukrainian political prisoner, Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Study, 1984, 401 pp., ISBN 978-0920862179.

- Za Chidnim Obriyam - (Beyond The Eastern Horizon),Paris, Baltimore: Smoloskyp, 1974, 447 pp.

- Hava Volovich, My Tale is Told: Women's Memoirs of Gulag, by Simeon Vilensky, Indiana University Press, 1999

- Solzhenitsyn's, Shalamov's, Ginzburg's works at Lib.ru (in original Russian)

- Вернон Кресс (alias of Петр Зигмундович Демант) "Зекамерон XX века", autobiographical novel (بالروسية)

- Бирюков А.М. Колымские истории: очерки. Новосибирск, 2004

- روايات

- ألكسندر سولجنيتسين

- One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, Signet Classic, 158 pp., ISBN 0-451-52310-5.

- The First Circle, Northwestern University Press, 580 pp., ISBN 978-0810115903.

- Chabua Amirejibi, Gora Mborgali. Tbilisi, Georgia: Chabua, 2001, 650 pp., ISBN 99940-734-1-9.

- Mehdi Husein (1905-1965), "Underground Rivers Flow Into the Sea" (Excerpts - First Novel About Exile to the Gulag by an Azerbaijani Writer)

- Martin Amis, House of Meetings. New York: Vintage Books, 2006, 242 pp., ISBN 978-1-4000-9601-5.

- Herta Müller, Everything I Possess I Carry With Me

- Martin Booth, The Industry Of Souls. United Kingdom: Dewi Lewis Publishing, 1998, 250 pp., ISBN 0-312-26753-3.

- سينما وتلفزيون

- The Way Back 2010 war drama film about a group of prisoners who escape from a Siberian Gulag camp during World War II.

وصلات خارجية

| Gulag

]].- GULAG: Many Days, Many Lives, Online Exhibit, Center for History and New Media, George Mason University

- Gulag: Forced Labor Camps, Online Exhibition, Open Society Archives

- The website of the State Museum of GULAG History in Moscow

- The website of the Virtual Gulag Museum projected by the scientific information center Memorial

- Sound Archives. European Memories of the Gulag

- Gulag prisoners at work, 1936-1937 Photoalbum at NYPL Digital Gallery

- The GULAG, Revelations from the Russian Archives at Library of Congress

- GULAG 113, Canadian documentary film about Estonians in the GULAG, website includes photos video.

- Gulag Photo album (prisoners of Kolyma and Chukotka labor camps, 1951-55)

- Pages about the Kolyma camps and the evolution of GULAG

- The Soviet Gulag Era in Pictures - 1927 through 1953

- The Economics of the GULAG

- Stories from the Gulag Dossier by Radio France Internationale in English

- interactive map of GULAG (in German)

- I Was a Slave in Russia: An American Tells His Story Archive.org online ebook.

- Recollections of Soviet Labor Camps, 1949-1955 Archive.org online ebook.

- Articles with dead external links from December 2011

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles containing روسية-language text

- گولاگ

- يوسف ستالين

- كلمات مستعارة من الروسية

- القمع السياسي في الاتحاد السوڤيتي

- قمع سياسي

- Penal labor

- القانون السوڤيتي

- تاريخ الاتحاد السوڤيتي وروسيا السوڤيتية

- سجن واحتجاز

- محتجزو الگولاگ