جمهورية نوڤگورود

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

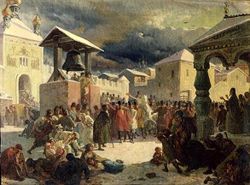

جمهورية نوڤگورود أو روس النوڤگورودية (روسية: Новгоро́дская респу́блика, النطق Novgorodskaya respublika; النطق الروسي: [nəvgɐˈrotskəjə rʲɪsˈpublʲɪkə]؛ Новгородскаѧ землѧ / Novgorodskaję zemlę، أرض نوڤگورود؛ إنگليزية: Novgorod Republic) كانت دولة قروسطية سلاڤية شرقية من القرن 12 إلى القرن 15، ممتدة من بحر البلطيق إلى شمال جبال الأورال، بما في ذلك مدينة نوڤگورود و مناطق بحيرة لادوگا في روسيا المعاصرة. وكان مواطنوها يشيرون إلى مدينتهم-الدولة بإسم "صاحب الجلالة (أو سيادة) لورد نوڤگورود الأكبر" (Gosudař Gospodin Velikij Novgorod)، أو كثيراً ما كانوا يسمونها "اللورد نوڤگورود الأكبر" (Gospodin Velikij Novgorod). ازدهرت الجمهورية كالجزء الأقصى شرقاً في العصبة الهانزية.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

التاريخ

أصل الاسم

In the middle of the 9th century, Nevogardas was a name used to describe Viking staging posts on the trade route from the Baltic Sea to the Byzantine Empire. There is a theory that in fact it was not Novgorod as misinterpreted by later chroniclers (as stated by dendrochronology, Novgorod was founded only in the middle of the 10th century),[1] but Nevo Gardas – Viking settlements on Lake Ladoga, as in one of Nestor's chronicles from the 12th century he mentions a lake called "the Great Nevo", a clear link to the Neva River and, possibly furthermore, to Finnish nevo "sea" or neva "bog, quagmire".[2]

التاريخ المبكر حتى النزاعات مع سوزدال

أرض نوڤگورود

مقالة مفصلة: أرض نوڤگورود

مقالة مفصلة: أرض نوڤگورود

الحكم

الاقتصاد

العلاقات الخارجية

أثناء فترة روس الكييڤية, Novgorod was a trade hub at the northern end of both the Volga trade route and the "route from the Varangians to the Greeks" along the Dnieper river system. A vast array of goods were transported along these routes and exchanged with local Novgorod merchants and other traders. The merchants of Gotland retained the Gothic Court trading house well into the 12th century. Later German merchantmen also established tradinghouses in Novgorod. Scandinavian royalty would intermarry with Russian princes and princesses.

هانزا، والسويد والنظام الليڤوني

After the great schism, Novgorod struggled from the beginning of the 13th century against Swedish, Danish, and German crusaders. During the الحروب السويدية النوڤگورودية, the Swedes invaded lands where some of the population had earlier دفعت الجزية لنوڤگورود. The Germans had been trying to conquer the Baltic region since the late 12th century. Novgorod went to war 26 times with Sweden and 11 times with the Livonian Brothers of the Sword. The German knights, along with Danish and Swedish feudal lords, launched a series of uncoordinated attacks in 1240-1242. Novgorodian sources mention that a Swedish army was defeated in the Battle of the Neva in 1240. The Baltic German campaigns ended in failure after the Battle on the Ice in 1242. After the foundation of the castle of ڤيبورگ in 1293 the Swedes gained a foothold in كارليا. On August 12, 1323, Sweden and Novgorod signed the Treaty of Nöteborg, regulating their border for the first time.

الغزو المنغولي وأعقابه

تمكنت جمهورية نوڤگورود من تفادي أهوال الغزو المنغولي لأنها كانت الإمارة الروسية الوحيدة التي خضعت للمنغول قبل الغزو وسلمياً.[3] Instead being formally conquered, the Republic paid a large bribe to Subutai in 1241, agreed to become a vassal, and later began to pay tribute to the خانات القبيل الذهبي. في 1259، وصل جباة الضرائب وموظفي الإحصاء المنغول إلى المدينة، مما أشعل اضطرابات سياسية دفعت ألكسندر نيڤسكي إلى معاقبة عدد من مسئولي البلدات (بجدع أنوفهم) لعصيانهم إياه كالأمير الأكبر لڤلاديمير (وسرعان ما سيصبح جابي ضرائب الخان في روسيا) and his Mongol overlords. In the 14th century, raids by Novgorod pirates, or ushkuiniki,[4] sowed fear as far as قازان و أستراخان، assisting Novgorod in wars with Muscovy.

سقوط الجمهورية

Tver, Muscovy, and Lithuania fought over control of Novgorod and its enormous wealth from the 14th century. Upon becoming the Grand Prince of Vladimir, Mikhail Yaroslavich of Tver sent his governors to Novgorod. A series of disagreements with Mikhail pushed Novgorod towards closer ties with Muscovy during the reign of Grand Prince George. In part, Tver's proximity (the Tver Principality is contiguous with the Novgorodian Land) threatened Novgorod. It was feared that a Tverite prince would annex Novgorodian lands and thus weaken the Republic. At the time, though, Muscovy did not touch Novgorod, and since the Muscovite princes were further afield, they were more acceptable as princes of Novgorod. They could come to Novgorod's aid when needed but would be too far away to meddle too much in the Republic's affairs.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

أمير نوڤگورود

انظر أيضاً

الهامش

- ^ http://archaeology.nsc.ru/ru/publish/journal/doc/2009/371/9.pdf[bare URL PDF]

- ^ Evgeny Pospelov: Geographical Names of the World: Toponymic Dictionary. Second edition. Astrel, Moscow 2001, p. 106 f.

- ^ Frank McLynn, Genghis Khan (2015), 441.

- ^ Janet Martin, “Les Uškujniki de Novgorod: Marchands ou Pirates.” Cahiers du Monde Russe et Sovietique 16 (1975): 5-18.

وصلات خارجية

- All articles with bare URLs for citations

- Articles with bare URLs for citations from March 2022

- Articles with PDF format bare URLs for citations

- Articles containing Old East Slavic-language text

- Pages using infobox country or infobox former country with the flag caption or type parameters

- Pages using infobox country or infobox former country with the symbol caption or type parameters

- Articles containing روسية-language text

- Articles containing Church Slavonic-language text

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- دول وأقاليم تأسست في 1136

- Subdivisions of Kievan Rus'

- جمهورية نوڤگورود

- محطات تجارية للعصبة الهانزية

- بلدان سلاڤية سابقة

- انحلالات 1478

- Russian city-states

- جمهوريات سابقة