عظام العرافة

| عظام العرافة | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

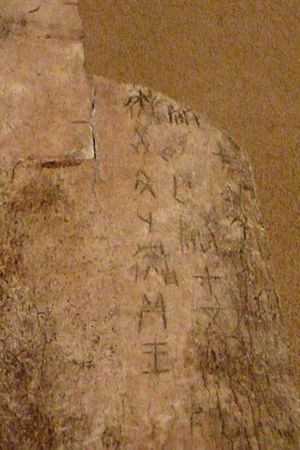

عظمة عرافة من أسرة شانگ، في متحف شانغهاي | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| الصينية | 甲骨 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| المعنى الحرفي | درقات وعظام | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

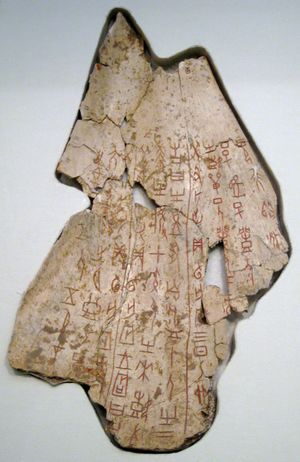

عظام العرافة (صينية: 甲骨؛ پنين: jiǎgǔ�؛ إنگليزية: Oracle bones) هي قطع من لوح كتف ثور أو بطن درقة السلحفاة، التي كانت تُستخدم للكهانة بالنار – وهي أحد أنواع الكهانة – في الصين القديمة، أساساً أثناء أواخر أسرة شانگ. كهانة لوح الكتف هي المصطلح الصحيح إذا كان لوح كتف الثورة هو المستخدم في الكهانة؛ وكهانة بطن درقة السلحفاة إذا كان بطن درقة السلحفاة هو المستخدم.

Diviners would submit questions to deities regarding future weather, crop planting, the fortunes of members of the royal family, military endeavors, and other similar topics.[1] These questions were carved onto the bone or shell in oracle bone script using a sharp tool. Intense heat was then applied with a metal rod until the bone or shell cracked due to thermal expansion. The diviner would then interpret the pattern of cracks and write the prognostication upon the piece as well.[2] Pyromancy with bones continued in China into the أسرة ژو, but the questions and prognostications were increasingly written with brushes and cinnabar ink, which degraded over time.

تحمل عظام العرافة أقدم مجمع بارز معروف للكتابة الصينية القديمة[أ] and contain important historical information such as the complete royal genealogy of the Shang dynasty.[ب] When they were discovered and deciphered in the early twentieth century, these records confirmed the existence of the Shang, which some scholars had until then doubted.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الاكتشاف

The Shang-dynasty oracle bones are thought to have been unearthed periodically by local farmers[9] since as early as the Sui and أسرة تانگ and perhaps starting as early as the Han dynasty,[10] but local inhabitants did not realize what the bones were and generally reburied them.[11] During the 19th century, villagers in the area digging in the fields discovered a number of bones and used them as "dragon bones" (صينية: 龍骨؛ پنين: lóng gǔ�), a reference to the traditional Chinese medicine practice of grinding up پلایستوسين fossils into tonics or poultices.[11][12] The turtle shell fragments were prescribed for malaria,[ت] while the other animal bones were used in powdered form to treat knife wounds.[13]

الحفريات الرسمية

النشر

Oracle bone inscriptions were published as they were discovered, in fascicles. Subsequently many collections of inscriptions were also published. The following are the main collections.

- 殷墟文字甲編 Yinxu wenzi jiabian

- 殷墟文字乙編 Yinxu wenzi yibian

- 殷墟文字丙編 Yinxu wenzi bingbian

- 殷虛書契前編 Yin xu shu qi qian bian

- 集殷虛文字楹帖彙編 Ji Yin xu wen zi ying tie hui bian

- 殷墟萃編 Yinxu cuibian

- 后上 Housshang

- 后下 Houxia

- 粹編 Cuibian

- 殷虛書契續編 yīn xū shū qì xù biān

- 亀甲 Kikkō

- 殷契摭佚續編 Yinqizhiyi xubian

- 殷契遺珠 Yinqi yizhu

- 京都大學人文科学研究所蔵甲骨文字 Kyōto daigaku jimbunkagaku kenkyūshozō kōkotsumoji

- 殷契佚存 Yiqi yicun

- 甲骨綴合編 Jiagu zhuihebian

- 鐵雲藏龜拾遺 Tieyun canggui shiyi

- 戰後京津新獲甲骨集 Zhanhou Jingjin xinhuo jiaguji (1954)

- 殷墟文字存真 Yinxu wenzi cunzhen

- 戰後寧滬新獲甲骨集 Zhanhou Ninghu xinhuo jiaguji (1951)

Observing that the citation of these different works was becoming unwieldy, an effort was made to comprehensively published all bones hitherto discovered. The result--the Jiǎgǔwén héjí (甲骨文合集) edited by Hu Houxuan, with its supplement edited by Peng Bangjiong, is the most comprehensive catalogue of oracle bone fragments. The 20 volumes contain reproductions of over 55,000 fragments. A separate work contains transcriptions of the inscriptions into standard characters.[14]

التسنين

The vast majority of the inscribed oracle bones were found at the Yinxu site in modern Anyang, and date to the reigns of the last nine kings of the Shang dynasty.[15] The diviners named on the bones have been assigned to five periods by Dong Zuobin:[16]

| الفترة | الملوك | الكهان العوام |

|---|---|---|

| I | Wu Ding[ث] | Què 㱿, Bīn 賓, Zhēng 爭, Xuān 宣 |

| II | Zu Geng, Zu Jia | Dà 大, Lǚ 旅, Xíng 行, Jí 即, Yǐn 尹, Chū 出 |

| III | Lin Xin, Kang Ding | Hé 何 |

| IV | Wu Yi, Wen Wu Ding | |

| V | Di Yi, Di Xin |

The kings were involved in divination in all periods, but in later periods most divinations were done personally by the king.[18] The extant inscriptions are not evenly distributed across these periods, with 55% coming from period I and 31% from periods III and IV.[19] A few oracle bones date to the beginning of the subsequent Zhou dynasty.

كهانة شانگ

Since divination (-mancy) was by heat or fire (pyro-) and most often on plastrons or scapulae, the terms pyromancy, plastromancy[ج] and scapulimancy are often used for this process.

المواد

التحضير

الكسر والتفسير

Divinations were typically carried out for the Shang kings in the presence of a diviner. A very few oracle bones were used in divination by other members of the royal family or nobles close to the king. By the latest periods, the Shang kings took over the role of diviner personally.[3]

الدليل الأثري على كهانة النار قبل آنيانگ

While the use of bones in divination has been practiced almost globally, such divination involving fire or heat has generally been found in Asia and the Asian-derived North American cultures.[20] The use of heat to crack scapulae (pyro-scapulimancy) originated in ancient China, the earliest evidence of which extends back to the 4th millennium BCE, with archaeological finds from Liaoning, but these were not inscribed.[21] In Neolithic China at a variety of sites, the scapulae of cattle, sheep, pigs and deer used in pyromancy have been found,[22] and the practice appears to have become quite common by the end of the third millennium BCE. Scapulae were unearthed along with smaller numbers of pitless plastrons in the Nánguānwài (南關外) stage at Zhengzhou, Henan; scapulae as well as smaller numbers of plastrons with chiseled pits were also discovered in the Lower and Upper Erligang stages.[23]

في مواقع أخرى

Four inscribed bones have been found at Zhengzhou in Henan: three with numbers 310, 311 and 312 in the Hebu corpus, and one containing a single character (ㄓ) which also appears in late Shang inscriptions. HB 310, which contained two brief divinations, has been lost, but is recorded in a rubbing and two photographs. HB 311 and 312 each contain a short sentence similar to the late Shang script. HB 312 was found in an upper layer of the Erligang culture. The others were found accidentally in river management earthworks, and so lack archaeological context. Pei Mingxiang argued that they predated the Anyang site. Takashima, referring to character forms and syntax, argues that they were contemporaneous with the reign of Wu Ding.[24][25]

A few inscribed oracle bones have also been unearthed in the Zhōuyuán, the original political center of the Zhou in Shaanxi and in Daxinzhuang, Jinan, Shandong. Some bones from the Zhouyuan are believed to be contemporaneous with the reign of Di Xin, the last Shang king.[26]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

عظام العرافة بعد شانگ

After the founding of Zhou, the Shang practices of bronze casting, pyromancy and writing continued. Oracle bones found in the 1970s have been dated to the Zhou dynasty, with some dating to the Spring and Autumn period. However, very few of those were inscribed. It is thought that other methods of divination supplanted pyromancy, such as numerological divination using milfoil (yarrow) in connection with the hexagrams of the I Ching, leading to the decline in inscribed oracle bones. However, evidence for the continued use of plastromancy exists for the Eastern Zhou, Han, Tang[27] and Qing[28] dynasty periods, and Keightley mentions use in Taiwan as late as 1972.[29]

ملاحظات

- ^ A tiny number of isolated mid to late Shang pottery, bone and bronze inscriptions may predate the oracle bones. However, the oracle bones are considered the earliest significant body of writing, due to the length of the inscriptions, the vast amount of vocabulary (very roughly 4000 graphs), and the sheer quantity of pieces found – at least 100,000 pieces[3][4] bearing millions of characters,[5] and around 5,000 different characters,[5] forming a full working vocabulary (Qiu 2000, p. 50 cites various statistical studies before concluding that "the number of Chinese characters in general use is around five to six thousand"). There are also inscribed or brush-written Neolithic signs in China, but they do not generally occur in strings of signs resembling writing; rather, they generally occur singly and whether or not these constitute writing or are ancestral to the Shang writing system is currently a matter of great academic controversy. They are also insignificant in number compared to the massive amounts of oracle bones found so far.[6][7][8]

- ^ Chou 1976, p. 12 cites two such scapulae, citing his own "商殷帝王本紀" Shāng–Yīn dìwáng bĕnjì, pp. 18–21.

- ^ Xu 2002, pp. 4–5 cites The Compendium of Materia Medica and includes a photo of the relevant page and entry.

- ^ Dong also included kings Pan Geng, Xiao Xin and Xiao Yi. However, few or perhaps no inscriptions can be reliably assigned to pre-Wu Ding reigns. Many scholars assume that earlier oracle bones from Anyang exist but have not yet been found.[17]

- ^ According to Keightley 1978a, p. 5, citing Yang Junshi 1963, the term plastromancy (from plastron + Greek μαντεία, "divination") was coined by Li Ji.

انظر أيضاً

المراجع

- ^ Keightley 1978a, pp. 33–35.

- ^ Keightley 1978a, pp. 40–42.

- ^ أ ب Qiu 2000, p. 61.

- ^ Keightley 1978a, p. xiii.

- ^ أ ب Qiu 2000, p. 49.

- ^ Qiu 2000.

- ^ Boltz 2003.

- ^ Woon 1987.

- ^ Qiu 2000, p. 60.

- ^ Chou 1976, p. 1, citing Wei Juxian 1939, "Qín-Hàn shi fāxiàn jiǎgǔwén shuō", in Shuōwén Yuè Kān, vol. 1, no.4; and He Tianxing 1940, "Jiǎgǔwén yi xianyu gǔdài shuō", in Xueshu (Shànghǎi), no. 1

- ^ أ ب Wilkinson 2000, p. 390.

- ^ Fairbank & Goldman 2006, p. 33.

- ^ Xu 2002, p. 4.

- ^ Wilkinson 2000, pp. 400–401.

- ^ Keightley 1978a, pp. xiii, 139.

- ^ Keightley 1978a, pp. 31, 92–93, 203.

- ^ Keightley 1978a, pp. 97–98, 139–140, 203.

- ^ Keightley 1978a, p. 31.

- ^ Keightley 1978a, pp. 139–140.

- ^ Keightley 1978a, pp. 3, 4, n. 11 and 12.

- ^ Keightley 1978a, p. 3.

- ^ Keightley 1978a, pp. 3, 6, n.16.

- ^ Keightley 1978a, p. 8, note 25, citing KKHP 1973.1, pp. 70, 79, 88, 91, plates 3.1, 4.2, 13.8.

- ^ Takashima 2012, pp. 143–160.

- ^ Qiu 2000, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Takashima 2012, p. 141.

- ^ Keightley 1978a, p. 4 n.4.

- ^ Keightley 1978a, p. 9, n.30, citing Hu Xu 1782–1787, ch. 4, p.3b on use in Jiangsu

- ^ cites Zhāng Guangyuan 1972

<ref> بالاسم " FOOTNOTEKeightley1978a9 " المحددة في <references> لها سمة المجموعة " " والتي لا تظهر في النص السابق.الأعمال المذكورة

- Boltz, William G. (2003). The origin and early development of the Chinese writing system. New Haven, CT: American Oriental Society. ISBN 0-940490-18-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) Pbk. ed. with minor corr. and a new preface. - Chou, Hung-hsiang 周鴻翔 (1976). Oracle Bone Collections in the United States. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-09534-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fairbank, John King; Goldman, Merle (2006). China : a new history (2nd enl. ed.). Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01828-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Keightley, David N. (1978a). Sources of Shang history : the oracle-bone inscriptions of Bronze Age China. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-02969-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) Paperback 2nd edition (1985) ISBN 0-520-05455-5. - ——— (1978b). "The Bamboo Annals and Shang-Chou Chronology". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 38 (2): 423–438. JSTOR 2718906.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ——— (2000). The ancestral landscape: time, space, and community in late Shang China, ca. 1200–1045 B.C. Berkeley: University of California, Berkeley. ISBN 1-55729-070-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Li, Xueqin (2002). "The Xia-Shang-Zhou Chronology Project: Methodology and Results". Journal of East Asian Archaeology. 4: 321–333. doi:10.1163/156852302322454585.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Qiu, Xigui (2000). Chinese writing (Wenzixue gaiyao). Transl. by Gilbert L. Mattos and Jerry Norman. Berkeley: Society for the Study of Early China. ISBN 1-55729-071-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Takashima, Ken-ichi (2012). "Literacy to the South and the East of Anyang in Shang China: Zhengzhou and Daxinzhuang". In Li, Feng; Branner, David Prager (eds.). Writing and Literacy in Early China: Studies from the Columbia Early China Seminar. University of Washington Press. pp. 141–172. ISBN 978-0-295-80450-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wilkinson, Endymion (2000). Chinese History: A Manual (2nd ed.). Harvard University Asia Center. ISBN 978-0-674-00249-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wilkinson, Endymion (2015). Chinese History: A New Manual (4th ed.). Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Asia Center. ISBN 978-0-674-08846-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|authormask=ignored (|author-mask=suggested) (help) - Woon, Wee Lee 雲惟利 (1987). Chinese Writing: Its Origin and Evolution. Macau: University of East Asia.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) Now issued by Joint Publishing, Hong Kong. - Xu, Yahui (許雅惠 Hsu Ya-huei) (2002). Ancient Chinese Writing, Oracle Bone Inscriptions from the Ruins of Yin. English translation by Mark Caltonhill and Jeff Moser. Taibei: National Palace Museum. ISBN 978-957-562-420-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) Illustrated guide to the Special Exhibition of Oracle Bone Inscriptions from the Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica. Govt. Publ. No. 1009100250. - York, Geoffrey. "The Unsung Canadian Some Knew as 'Old Bones'". The Globe and Mail. March 27, 2017. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- Zhang, Peiyu (2002). "Determining Xia–Shang–Zhou Chronology through Astronomical Records in Historical Texts". Journal of East Asian Archaeology. 4: 335–357. doi:10.1163/156852302322454602.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

وصلات خارجية

- Oracle bones, United College Library, Chinese University of Hong Kong. Includes 45 inscribed fragments.

- Oracle Bone Collection, Institute of History and Philology, Taipei City.

- High-resolution digital images of oracle bones, Cambridge Digital Library.

- Yīnxū shūqì 殷虛書契 by Luo Zhenyu – a collection of rubbings or oracle bone fragments.

- Guījiǎ shòugǔ wénzì 龜甲獸骨文字 by Hayashi Taisuke – another collection of rubbings.

- 四方风 or Winds of the Four Directions World Digital Library. مكتبة الصين الوطنية.