أسماك غضروفية

| الأسماك الغضروفية | |

|---|---|

| |

| القرش الأبيض الكبير. | |

| التصنيف العلمي | |

| مملكة: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Subphylum: | |

| Infraphylum: | |

| Class: | الغضروفيات هسكلي، 1880

|

| تحت رتب | |

الغضروفيات Chondrichthyes ( /kɒnˈdrɪkθɪ.iːz/؛ من اليونانية χονδρ- chondr- 'غضروف'، ἰχθύς ichthys 'أسماك')، هي رتبة تضم الأسماك الغضروفية: وهي عبارة عن فقاريات فكية بزوجين من الزعانف، وفتحتي أنف، وحراشف، وقلب ذو أربع حجرات، وهيكل الغضاريف بدلاً من العظم. تنقسم الرتبة إلى تحت رتبتين: صفيحيات الخياشيم Elasmobranchii (تضم القروش، الشفنينيات، الورنك، والكوسج) وكاملة الرأس Holocephali (وتضم أنواع مثل الكايميرا، وتسمى أحياناً القروش الشبح، والتي تقع أحياناً في رتبة منفصلة خاصة بها).

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

التشريح

تملك الأسماك الغضروفية ما يتراوح من 5 إلى 7 خياشيم طولية على كل جانب من جسمها. القروش والشفانين تتكاثر بتمرير المنى من الذكر إلى الأنثى، ويَستخدم الذكر زعانف لتثبيت نفسها على جسمها زعانف خاصة تسمّى "المَشابك"،[3] ملتحقة بزعانفها الحوضية. وعلى عكس معظم الأسماك، فإن الأسماك الغضروفية تتكاثر بتخصيب داخلي. وعندما تتطور البيوض المخصبة، فإنها تغلف بقشرة قوية وتوضع في الماء، أو إما أن تغلف بقشرة رقيقة وتبقى في الجسم حتى تفقس.

تملك الغضروفيات أسناناً ذات مقاومة عالية للانحلال. كقاعدة عامة، استبدال الأسنان منخفض نسبياً عند القروش القديمة والغضروفيات الأخرى، لكن الأمر مختلف عند القروش الحديثة. فيُمكن لقرش أن يَستبدل أسنانه خلال أيام، ويُمكنه أن يُنتج مئات أو حتى آلاف الأسنان خلال حياته. وهناك فائدة لمعدل إنتاج الأسنان المذهل هذا، حيث أن أسنان القروش الحديثة هي الأغنى نموذجياً من بين أحافير الفقاريات في الترسبات البحرية العائدة إلى كل من العصر الطباشيري والدهر الحديث. تتميّز أسماك السفن والشفانين بامتداد زعانفها الصدرية إلى قرص، يَكون ممتداً جيداً عند بعضها حتى الخطم.[4]

الهيكل الغضروفي

الزوائد

غطاء الجسم

الجهاز التنفسي

الجهاز المناعي

التكاثر

التصنيف

| تحت رتبة الأسماك الغضروفية | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| ظاهرة الخياشيم Elasmobranchii |  |

Elasmobranchii is a subclass that includes the sharks and the rays and skates. Members of the elasmobranchii have no swim bladders, five to seven pairs of gill clefts opening individually to the exterior, rigid dorsal fins, and small placoid scales. The teeth are in several series; the upper jaw is not fused to the cranium, and the lower jaw is articulated with the upper. The eyes have a tapetum lucidum. The inner margin of each pelvic fin in the male fish is grooved to constitute a clasper for the transmission of sperm. These fish are widely distributed in tropical and temperate waters.[5] | |

| كاملة الرأس Holocephali |  |

كاملة الرأس Holocephali is a subclass of which the order Chimaeriformes is the only surviving group. This group includes the rat fishes (e.g., Chimaera), rabbit-fishes (e.g., Hydrolagus) and elephant-fishes (Callorhynchus). Today, they preserve some features of elasmobranch life in Paleaozoic times, though in other respects they are aberrant. They live close to the bottom and feed on molluscs and other invertebrates. The tail is long and thin and they move by sweeping movements of the large pectoral fins. There is an erectile spine in front of the dorsal fin, sometimes poisonous. There is no stomach (that is, the gut is simplified and the 'stomach' is merged with the intestine), and the mouth is a small aperture surrounded by lips, giving the head a parrot-like appearance.

The fossil record of the Holocephali starts in the Devonian period. The record is extensive, but most fossils are teeth, and the body forms of numerous species are not known, or at best poorly understood. | |

| الرتب الموجودة من الأسماك الغضروفية | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| المجموعة | الرتبة | صورة | الاسم الشائع | التسمية | الفصائل | الجنس | النوع | ملاحظات | ||||

| الإجمالي | ||||||||||||

| قروش گاليان |

شبيهات الغضروفيات |

|

القروش الأرضية |

كومپاگنو، 1977 | 8 | 51 | >270 | 7 | 10 | 21 | ||

| Heterodontiformes |

|

bullhead sharks |

L. S. Berg, 1940 | 1 | 1 | 9 | ||||||

| Lamniformes |

|

mackerel sharks |

L. S. Berg, 1958 | 7 +2 extinct |

10 | 16 | 10 | |||||

| Orectolobiformes |

|

carpet sharks |

Applegate, 1972 | 7 | 13 | 43 | 7 | |||||

| Squalomorph sharks |

Hexanchiformes |

|

frilled and cow sharks |

de Buen, 1926 | 2 +3 extinct |

4 +11 extinct |

6 +33 extinct |

|||||

| Pristiophoriformes | sawsharks | L. S. Berg, 1958 | 1 | 2 | 6 | |||||||

| Squaliformes |

|

dogfish sharks |

1 | 2 | 29 | 1 | 6 | |||||

| Squatiniformes |

|

angel sharks |

Buen, 1926 | 1 | 1 | 23 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||

| Rays | Myliobatiformes |

|

stingrays and relatives |

Compagno, 1973 | 10 | 29 | 223 | 1 | 16 | 33 | ||

| Pristiformes |

|

sawfishes | 1 | 2 | 5-7 | 5-7 | ||||||

| Rajiformes |

|

skates and guitarfishes |

L. S. Berg, 1940 | 5 | 36 | >270 | 4 | 12 | 26 | |||

| Torpediniformes |

|

electric rays |

de Buen, 1926 | 2 | 12 | 69 | 2 | 9 | ||||

| Holocephali | Chimaeriformes |

|

chimaera | Obruchev, 1953 | 3 +2 extinct |

6 +3 extinct |

39 +17 extinct |

|||||

| Taxonomy according to Leonard Compagno, 2005[6] with additions from [7] |

|---|

* position uncertain |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

التطور

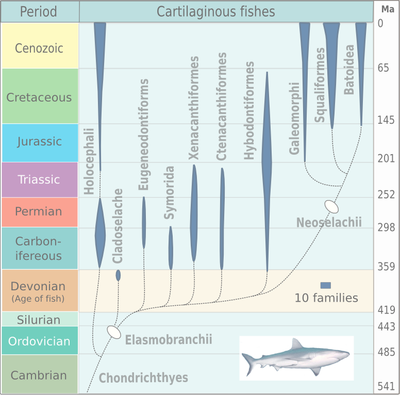

ربما تكون الغضروفيات هي أقدم الفقاريات المعروفة، فقد بدأت أولى الأسماك الشبيهة بالقروش بالظهور في رواسب الأردوفيسي المتأخر والسلوري السفلي (بالرغم من أن الشفانين والسفن لم يَظهرا حتى العصر الجوراسي). لكن بالرغم من هذا، فإن أولى الأسماك المجزوم بأنها قروش لم تظهر حتى الديفوني السفلي. وقد ازداد تنوّع وانتشار الأحافير بشكل ضخم في العصر الديفوني العلوي و العصر الفحمي، ثم انحدر نوعاً ما بعد ذلك، وأخيراً ازداد مجدداً في العصرين الطباشيري والثلاثي. وحالياً، تمثل القروش وأقاربها ثاني أكثر مجموعات الأسماك الحية تنوعاً وغنى.[4]

| العصر الديڤوني (419–359 mya) | ||||||

|

Cladoselache | Cladoselache was the first abundant genus of primitive shark, appearing about 370 Ma.[9] It grew to 6 feet (1.8 m) long, with anatomical features similar to modern mackerel sharks. It had a streamlined body almost entirely devoid of scales, with five to seven gill slits and a short, rounded snout that had a terminal mouth opening at the front of the skull.[9] It had a very weak jaw joint compared with modern-day sharks, but it compensated for that with very strong jaw-closing muscles. Its teeth were multi-cusped and smooth-edged, making them suitable for grasping, but not tearing or chewing. Cladoselache therefore probably seized prey by the tail and swallowed it whole.[9] It had powerful keels that extended onto the side of the tail stalk and a semi-lunate tail fin, with the superior lobe about the same size as the inferior. This combination helped with its speed and agility which was useful when trying to outswim its probable predator, the heavily armoured 10 metres (33 ft) long placoderm fish Dunkleosteus.[9] | ||||

| العصر الفحمي |

العصرالفحمي (359–299 Ma): Sharks underwent a major evolutionary radiation during the Carboniferous.[10] It is believed that this evolutionary radiation occurred because the decline of the placoderms at the end of the Devonian period caused many environmental niches to become unoccupied and allowed new organisms to evolve and fill these niches.[10] | |||||

|

Orthacanthus senckenbergianus | The first 15 million years of the Carboniferous has very few terrestrial fossils. This gap in the fossil record, is called Romer's gap after the American palaentologist Alfred Romer. While it has long been debated whether the gap is a result of fossilisation or relates to an actual event, recent work indicates that the gap period saw a drop in atmospheric oxygen levels, indicating some sort of ecological collapse.[11] The gap saw the demise of the Devonian fish-like ichthyostegalian labyrinthodonts, and the rise of the more advanced temnospondyl and reptiliomorphan amphibians that so typify the Carboniferous terrestrial vertebrate fauna. | ||||

|

Stethacanthidae |

As a result of the evolutionary radiation, carboniferous sharks assumed a wide variety of bizarre shapes; e.g., sharks belonging to the family Stethacanthidae possessed a flat brush-like dorsal fin with a patch of denticles on its top.[10] Stethacanthus' unusual fin may have been used in mating rituals.[10] Apart from the fins, Stethacanthidae resembled Falcatus (below). | ||||

|

Falcatus | Falcatus is a genus of small cladodont-toothed sharks which lived 335–318 Ma. They were about 25-30 cm (10-12 inches) long.[12] They are characterised by the prominent fin spines that curved anteriorly over their heads. | ||||

|

Orodus | Orodus is another shark of the Carboniferous, a genus from the family Orodontidae that lived into the early Permian from 303 to 295 Ma. It grew to 2 m (7 ft) in length. | ||||

| Permian | Permian (298–252 Ma): The Permian ended with the most extensive extinction event recorded in paleontology: the Permian-Triassic extinction event. 90% to 95% of marine species became extinct, as well as 70% of all land organisms. Recovery from the Permian-Triassic extinction event was protracted; land ecosystems took 30M years to recover,[13] and marine ecosystems took even longer.[14] | |||||

| العصر الثلاثي | العصر الثلاثي (252–201 Ma): The fish fauna of the Triassic was remarkably uniform, reflecting the fact that very few families survived the Permian extinction. In turn, the Triassic ended with the Triassic–Jurassic extinction event. About 23% of all families, 48% of all genera (20% of marine families and 55% of marine genera) and 70% to 75% of all species went extinct.[15] | |||||

| العصر الجوراسي | العصر الجوراسي (201–145 Ma): The end of the Cretaceous was marked by the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event (K-Pg extinction). There are substantial fossil records of jawed fishes across the K–T boundary, which provides good evidence of extinction patterns of these classes of marine vertebrates. Within cartilaginous fish, approximately 80% of the sharks, rays, and skates families survived the extinction event,[16] and more than 90% of teleost fish (bony fish) families survived.[17] | |||||

| العصرالطباشيري | العصرالطباشيري (145–66 Ma): | |||||

|

Squalicorax falcatus | Squalicorax falcatus is a lamnoid shark from the Cretaceous | ||||

|

Ptychodus | Ptychodus is a genus of extinct hybodontiform shark which lived from the late Cretaceous to the Paleogene.[18][19] Ptychodus mortoni (pictured) was about 32 feet long (10 meters) and was unearthed in Kansas, United States.[20] | ||||

| الدهر الحديث |

الدهر الحديث (65 Ma to present): The current era has seen great diversification of bony fishes. | |||||

|

Megalodon | Megalodon is an extinct species of shark that lived about 28 to 1.5 Ma. It looked much like a stocky version of the great white shark, but was much larger with fossil lengths reaching 20.3 metres (67 ft).[21] Found in all oceans[22] it was one of the largest and most powerful predators in vertebrate history,[21] and probably had a profound impact on marine life.[23] | ||||

| رتب منقرضة من الأسماك الغضروفية | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| المجموعة | الرتبة | صورة | الاسم الشائع | التسمية | الفصائل | الجنس | النوع | ملاحظات | |

| كاملة الأس | †Orodontiformes | ||||||||

| †Petalodontiformes |

|

||||||||

| †Helodontiformes | |||||||||

| †Iniopterygiformes |

|

||||||||

| †Debeeriiformes | |||||||||

| †Eugeneodonti formes |

|

[24] | |||||||

| †Psammodonti formes |

Position uncertain | ||||||||

| †Copodontiformes | |||||||||

| †Squalorajiformes | |||||||||

| †Chondrenchelyi formes |

|||||||||

| †Menaspiformes | |||||||||

| †Coliodontiformes | |||||||||

| Squalomorph sharks |

†Protospinaci- formes |

||||||||

| Other | †Squatinactiformes |

|

|||||||

| †Protacrodonti- formes |

|||||||||

| †Cladoselachi- formes |

|

||||||||

| †Xenacanthiformes |

|

||||||||

| †Ctenacanthi- formes |

|

||||||||

| †Hybodontiformes |

|

||||||||

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

التاريخ التطوري

Subphylum الفقاريات └─Infraphylum Gnathostomata ├─Placodermi — extinct (armored gnathostomes) └Eugnathostomata (true jawed vertebrates) ├─Acanthodii (stem cartilaginous fish) └─Chondrichthyes (true cartilaginous fish) ├─Holocephali (chimaeras + several extinct clades) └Elasmobranchii (shark and rays) ├─Selachii (true sharks) └─Batoidea (rays and relatives) ملاحظة: الخطوط توضح العلاقات التطورية.

انظر أيضاً

المصادر

Citations

- ^ Botella, H.A; Donoghue, P.C.J.; Martínez-Pérez, C. (2009). "Enameloid microstructure in the oldest known chondrichthyan teeth". Acta Zoologica. 90 (Supplement): 103–108. doi:10.1111/j.1463-6395.2008.00337.x. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Chondrichthyes". PalaeoDB. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ طائفة الأسماك الغضروفية: القروش - الشفانين - السفن. تاريخ الولوج 3-10-2010.

- ^ أ ب العصر الديفوني: المزيد حول الأسماك الغضروفية. تاريخ الولوج 3-10-2010.

- ^ Bigelow, Henry B.; Schroeder, William C. (1948). Fishes of the Western North Atlantic. Sears Foundation for Marine Research, Yale University. pp. 64–65. ASIN B000J0D9X6.

- ^ Leonard Compagno (2005) Sharks of the World. ISBN 9780691120720.

- ^ Haaramo, Mikko. Chondrichthyes – Sharks, Rays and Chimaeras. Retrieved 2013-10-22.

- ^ Benton, M. J. (2005) Vertebrate Palaeontology, Blackwell, 3rd edition, Fig 7.13 on page 185.

- ^ أ ب ت ث The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals 1999, p. 26.

- ^ أ ب ت ث R. Aidan Martin. "A Golden Age of Sharks". Biology of Sharks and Rays. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Ward, P.; Labandeira, C.; Laurin, M.; Berner, R. A. (2006). "Confirmation of Romer's Gap is a low oxygen interval constraining the timing of initial arthropod and vertebrate terrestrialization". Proceedings of the National Academy of Science. 103 (45): 16818–16822. Bibcode:2006PNAS..10316818W. doi:10.1073/pnas.0607824103. PMC 1636538. PMID 17065318.

- ^ http://www.sju.edu/research/bear_gulch/pages_fish_species/Falcatus_falcatus.php Fossil Fish of Bear Gulch 2005 by Richard Lund and Eileen Grogan Accessed 2009-01-14

- ^ Sahney, S. and Benton, M.J. (2008). "Recovery from the most profound mass extinction of all time" (PDF). Proceedings of the Royal Society: Biological. 275 (1636): 759–65. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.1370. PMC 2596898. PMID 18198148.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Baez. John (2006) Extinction University of California. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- ^ "extinction". Math.ucr.edu. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ MacLeod, N; Rawson, PF; Forey, PL; Banner, FT; Boudagher-Fadel, MK; Bown, PR; Burnett, JA; Chambers, P; Culver, S; Evans, SE; Jeffery, C; Kaminski, MA; Lord, AR; Milner, AC; Milner, AR; Morris, N; Owen, E; Rosen, BR; Smith, AB; Taylor, PD; Urquhart, E; Young, JR (1997). "The Cretaceous–Tertiary biotic transition". Journal of the Geological Society. 154 (2): 265–292. doi:10.1144/gsjgs.154.2.0265.

- ^ Patterson, C (1993). Osteichthyes: Teleostei. In: The Fossil Record 2 (Benton, MJ, editor). Springer. pp. 621–656. ISBN 0-412-39380-8.

- ^ Fossils (Smithsonian Handbooks) by David Ward (Page 200)

- ^ The paleobioloy Database Ptychodus entry accessed on 8/23/09

- ^ "BBC - Earth News - Giant predatory shark fossil unearthed in Kansas"

- ^ أ ب Wroe, S.; Huber, D. R.; Lowry, M.; McHenry, C.; Moreno, K.; Clausen, P.; Ferrara, T. L.; Cunningham, E.; Dean, M. N.; Summers, A. P. (2008). "Three-dimensional computer analysis of white shark jaw mechanics: how hard can a great white bite?" (PDF). Journal of Zoology. 276 (4): 336–342. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2008.00494.x.

- ^ Pimiento, Catalina; Dana J. Ehret; Bruce J. MacFadden; Gordon Hubbell (May 10, 2010). Stepanova, Anna (ed.). "Ancient Nursery Area for the Extinct Giant Shark Megalodon from the Miocene of Panama". PLoS ONE. Panama: PLoS.org. 5 (5): e10552. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...510552P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010552. PMC 2866656. PMID 20479893. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Lambert, Olivier; Bianucci, Giovanni; Post, Klaas; de Muizon, Christian; Salas-Gismondi, Rodolfo; Urbina, Mario; Reumer, Jelle (1 July 2010). "The giant bite of a new raptorial sperm whale from the Miocene epoch of Peru". Nature. Peru. 466 (7302): 105–108. Bibcode:2010Natur.466..105L. doi:10.1038/nature09067. PMID 20596020.

- ^ Tapanila, L; Pruitt, J; Pradel, A; Wilga, C; Ramsay, J; Schlader, R; Didier, D (2013). "Jaws for a spiral-tooth whorl: CT images reveal novel adaptation and phylogeny in fossil Helicoprion" (PDF). Biology Letters. 9: 20130057. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2013.0057.

قراءات إضافية