هرمز الرابع

| هرمز الرابع 𐭠𐭥𐭧𐭥𐭬𐭦𐭣 Hormizd IV | |

|---|---|

| شاه فارس | |

عملة هرمز الرابع، عُثر عليها في سپاهان. | |

| Shahanshah of the Sasanian Empire | |

| العهد | 579–590 |

| سبقه | كسرى الأول |

| تبعه | بهرام چوبين (rival king) Khosrow II (successor) |

| وُلِد | ح. 540 |

| توفي | 590 (aged 49–50) قطسيفون |

| الزوج | See below |

| الأنجال | See below |

| البيت | House of Sasan |

| الأسرة | الأسرة الساسانية |

| الأب | كسرى الأول |

| الأم | أميرة خزرية |

| الديانة | الزرادشتية |

هُرمُز الرابع (فارسية: هرمز چهارم؛ عاش 530 في بغداد، توفي 590 في بغداد) كان الملك الثاني والعشرين على الدولة الساسانية في بلاد فارس الذي حكم في الفترة 579 - 590)، بعد أبيه كسرى الأول. اسمه هرمز بن كسرى أنو شِروان بن قباذ .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

صفاته

اتصف هرمز الرابع التجبر والعنف، إلا أنه لم يكن عديم الشفقة. حكى عنه الطبري قصصاً مميزة . حمى هرمز عامة الشعب وفرض انضباطاً حاداً في جيشه ومحكمته. ولكن عندما وصل إلى العرش في عام 579 قتل أخوته. ورث عن أبيه.

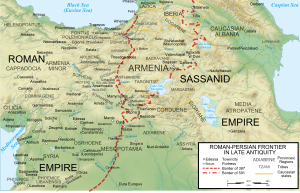

الهجوم على الإمبراطورية البيزنطية

شن الهجوم ضد الإمبراطورية البيزنطية والأتراك. مفاوضات السلام بدأت بواسطة الإمبراطور تيبريوس الثاني، لكن هرمز الرابع رفض ترك أي شيء بغطرسة فتوحات أبيه. في عام 588 قام جنرال هرمز الرابع، وهو بهرام تشوبين (الذي أصبح لاحقاً الملك بهرام السادس)، قام بهزيمة الأتراك. ولكنه في العام التالي (589) هُزِم من قبل الرومان.

The Byzantines were successful at their endeavors, securing a noteworthy victory under the commanders Cours and John Mystacon, albeit also suffering a defeat at the hands of the Sasanians.[1] In early 580, the clients and vassals of the Sasanians, the Lakhmids, were defeated at the hands of the Ghassanids, vassals of the Byzantines.[1] In the same year, a Byzantine army ravaged Garamig ud Nodardashiragan, reaching as far as Media.[2][3] Around the same time, Hormizd appointed Khosrow as the governor of Caucasian Albania, who negotiated with the Iberian aristocracy and won their support, so successfully bringing Iberia back under Sasanian rule.[2][4]

The following year, an ambitious campaign by the Byzantine commander Maurice, supported by Ghassanid forces under al-Mundhir III, targeted the Sasanian capital of Ctesiphon. The combined force moved south along the river Euphrates, accompanied by a fleet of ships. The army stormed the fortress of Anatha and moved on until it reached the region of Beth Aramaye in central Mesopotamia, near Ctesiphon. There they found the bridge over the Euphrates destroyed by the Iranians.[5][6] In response to Maurice's advance, the Iranian general Adarmahan was ordered to operate in northern Mesopotamia, threatening the Byzantine army's supply line.[7] Adarmahan raided Osrhoene, and was successful in capturing its capital, Edessa.[8] He then marched his army toward Callinicum on the Euphrates. With the possibility of a march to Ctesiphon gone, Maurice was forced to retreat. The retreat was arduous for the tired army, and Maurice and al-Mundhir exchanged recriminations for the expedition's failure. However, they cooperated in forcing Adarmahan to withdraw, and defeated him at Callinicum.[9]

Tiberius tried afterwards to renew negotiations by sending Zachariah to the frontier to meet Andigan.[10] The negotiations broke off once more after Andigan attempted to pressurize him by drawing the attention of the nearby Iranian contingent led by Tamkhosrow.[10] In 582, Tamkhosrow, along with Adarmahan, invaded Byzantine territory and headed for the town of Constantina. Maurice, who had been expecting and preparing for such an attack, fought the Iranians outside the city in June 582. The Iranian army suffered a heavy defeat, and Tamkhosrow was killed.[11][10] Not long afterwards, the deteriorating physical condition of Tiberius forced Maurice to return immediately to Constantinople to assume the crown.[3] Meanwhile, John Mystacon, who had replaced Maurice as the commander of the east, attacked the Sasanians at the junction of the Nymphius and the Tigris, but was defeated and forced to withdraw.[12] He was shortly replaced by Philippicus.[12] The war continued inconclusively through raids and counter-raids, punctuated by abortive peace talks—the one significant clash was a Byzantine victory at the Battle of Solachon in 586.[13] The war ultimately achieved very little for either side.[3]

الغزوات التوركية في الشرق

In 588, the Turkic Khagan Bagha Qaghan (known as Sabeh/Saba in Persian sources), together with his Hephthalite subjects, invaded the Sasanian territories south of the Oxus, where they attacked and routed the Sasanian soldiers stationed in Balkh. After conquering the city, they proceeded to take Talaqan, Badghis, and Herat.[14] In a council of war, Bahram Chobin of the Parthian Mihranid family was chosen to lead an army against them and was given the governorship of Khorasan. Bahram's army, supposedly consisting of 12,000 hand-picked horsemen,[15] ambushed a large army of Turks and Hephthalites in April 588, at the Battle of Hyrcanian Rock.[16] In 589 he retook Balkh, where he captured the Turkic treasury and the golden throne of the Khagan.[17] He then proceeded to cross the Oxus river and won a decisive victory over the Turks, personally killing Bagha Qaghan with an arrowshot.[15][18] He managed to reach as far as Baykand, near Bukhara, and also contain an attack by the son of the deceased Khagan, Birmudha, whom Bahram had captured and sent to Ctesiphon.[17]

Birmudha was well received there by Hormizd, who forty days later had him sent back to Bahram with the order that the Turkic prince should get sent back to Transoxiana.[17] The Sasanians now held suzerainty over the Sogdian cities of Chach and Samarkand, where Hormizd minted coins.[17][أ] After Bahram's great victory against the Turks he was sent to Caucasus to repel an invasion of nomads, possibly the Khazars, where he was victorious. He was once again made commander of the Sasanian forces against the Byzantines, and successfully defeated a Byzantine force in Georgia. However, he then suffered a minor defeat by a Byzantine army on the banks of the Aras. Hormizd, who was jealous of Bahram, used this defeat as an excuse to dismiss him from his office, and had him humiliated.[19][15]

الاطاحة بالملك وقتله

بعد أن سمع بتمرد بهرام، حاول هرمز أن ينظّم مقاومة فعالة ضده بمحاولة اجتذاب ڤيستاهم وڤيندويه ونبلاء آخرين لصفه. إلا أن أولئك، حسب سبيوس، حذرهم ابنه خسرو الثاني من التحالف مع هرمز فلم يستجيبوا لهرمز، فحبسهم، إلا أن ڤيستاهم تمكن من الهرب. وقام الشقيقان بانقلاب في القصر وخلعوا هرمز وسملوا عينيه بعدما ثار بهرام عليه، وأعلن ابنه كسرى الثاني ملكاً. تختلف المراجع في طريقة قتل هرمز، بعضها يقول بأن قاتله هو ابنة كسرى الثاني والبعض الآخر يقول بأنه قُتِل بواسطة خدمه.

Hormizd then left for the Great Zab in order to cut communications between Ctesiphon and the Iranian soldiers on the Byzantine border.[4] Around that time the soldiers, who were situated outside Nisibis, the chief city in northern Mesopotamia, rebelled against Hormizd and pledged their allegiance to Bahram.[4] The influence and popularity of Bahram continued to grow: Sasanian loyalist forces sent north against the Iranian rebels at Nisibis were flooded with rebel propaganda.[4] The loyalist forces eventually also rebelled and killed their commander, which made the position of Hormizd become unsustainable. He decided to navigate the Tigris river and take sanctuary in al-Hira, the capital of the Lakhmids.[4]

During Hormizd's stay at Ctesiphon, he was overthrown in a seemingly bloodless palace revolution by his brothers-in-law Vistahm and Vinduyih, who according to the Syriac writer Joshua the Stylite, both "equally hated Hormizd".[4][20] They had Hormizd blinded with a red-hot needle, and put his oldest son Khosrow II (who was their nephew through his mother's side) on the throne.[21][4] Sometime in the summer of 590, the two brothers then had Hormizd killed, with at least the implicit approval of Khosrow II.[4] Nevertheless, Bahram continued his march to Ctesiphon, now with the pretext of claiming to avenge Hormizd.[17] Hormizd's death continued to be a controversial matter—a few years later, Khosrow II ordered the execution of both his uncles as well as other nobles who had a hand in the killing of his father.[4] A few decades later, Khosrow II, after being overthrown in a coup by his son Kavad II, was accused of regicide against his father.[22]

المصادر

تاريخ الأمم والملوك للطبري

Notes

- ^ The Sasanians only managed to retain Chach and Samarkand for a few years, until it was re-captured by the Turks, who seemingly also conquered the eastern Sasanian province of Kadagistan.[17]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

References

- ^ أ ب Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 162.

- ^ أ ب Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 163.

- ^ أ ب ت Shahbazi 2004, pp. 466–467.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ Howard-Johnston 2010.

- ^ Shahîd 1995, pp. 413–419.

- ^ Greatrex & Lieu 2002, pp. 163–165.

- ^ Shahîd 1995, p. 414.

- ^ Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 164.

- ^ Shahîd 1995, p. 416; Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 165.

- ^ أ ب ت Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 166.

- ^ Martindale, Jones & Morris 1992, pp. 1215–1216.

- ^ أ ب Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 167.

- ^ Greatrex & Lieu 2002, pp. 167–169; Whitby & Whitby 1986, pp. 44–49.

- ^ Rezakhani 2017, p. 177.

- ^ أ ب ت Shahbazi 1988, pp. 514–522.

- ^ Jaques 2007, p. 463.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Rezakhani 2017, p. 178.

- ^ Litvinsky & Dani 1996, pp. 368–369.

- ^ Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 172.

- ^ Shahbazi 1989, pp. 180–182.

- ^ Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 5: p. 49.

- ^ Pourshariati 2008, p. 155.

Sources

- Al-Tabari, Abu Ja'far Muhammad ibn Jarir (1985–2007). Ehsan Yar-Shater (ed.). The History of Al-Ṭabarī. Vol. 40 vols. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Axworthy, Michael (2008). A History of Iran: Empire of the Mind. New York: Basic Books. pp. 1–368. ISBN 978-0-465-00888-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Daryaee, Touraj (2014). Sasanian Persia: The Rise and Fall of an Empire. I.B.Tauris. pp. 1–240. ISBN 978-0857716668.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) قالب:Free access - Greatrex, Geoffrey; Lieu, Samuel N. C. (2002). The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars (Part II, 363–630 AD). New York, New York and London, United Kingdom: Routledge (Taylor & Francis). ISBN 0-415-14687-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Howard-Johnston, James (2010). "Ḵosrow II". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Online Edition. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jaques, Tony (2007). Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: F-O. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 1–1354. ISBN 9780313335389.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kia, Mehrdad (2016). The Persian Empire: A Historical Encyclopedia [2 volumes]: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1610693912.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Litvinsky, B. A.; Dani, Ahmad Hasan (1996). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The crossroads of civilizations, A.D. 250 to 750. Vol. III. UNESCO. ISBN 9789231032110.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) قالب:Free access - Martindale, John Robert; Jones, Arnold Hugh Martin; Morris, J., eds. (1992). The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire, Volume III: A.D. 527–641. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-20160-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Payne, Richard E. (2015). A State of Mixture: Christians, Zoroastrians, and Iranian Political Culture in Late Antiquity. Univ of California Press. pp. 1–320. ISBN 9780520961531.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Pourshariati, Parvaneh (2008). Decline and Fall of the Sasanian Empire: The Sasanian-Parthian Confederacy and the Arab Conquest of Iran (PDF). London and New York: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-645-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) قالب:Free access - Rezakhani, Khodadad (2017). "East Iran in Late Antiquity". ReOrienting the Sasanians: East Iran in Late Antiquity. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 1–256. ISBN 9781474400305. JSTOR 10.3366/j.ctt1g04zr8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) قالب:Registration required - Shahbazi, A. Sh. (1988). "Bahrām VI Čōbīn". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. III, Fasc. 5. London et al. pp. 514–522.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Shahbazi, A. Shapur (1989). "Besṭām o Bendōy". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. IV, Fasc. 2. pp. 180–182.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Shahbazi, A. Shapur (2004). "Hormozd IV". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. XII, Fasc. 5. pp. 466–467.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Shahîd, Irfan (1995). Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century, Volume 1. Washington, District of Columbia: Dumbarton Oaks. ISBN 978-0-88402-214-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Shayegan, M. Rahim (2004). "Hormozd I". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. XII, Fasc. 5. pp. 462–464.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Shayegan, M. Rahim (2017). "Sasanian political ideology". In Potts, Daniel T. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Iran. Oxford University Press. pp. 1–1021. ISBN 9780190668662.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tafazzoli, A. (1988). "Āẕīn Jošnas". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. III, Fasc. 3. p. 260.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - قالب:ODLA

- Warren, Soward. Theophylact Simocatta and the Persians. Sasanika.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) قالب:Free access - Whitby, Michael; Whitby, Mary (1986). The History of Theophylact Simocatta. Oxford, United Kingdom: Claredon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-822799-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Further reading

- Crawford, Peter (2013). The War of the Three Gods: Romans, Persians and the Rise of Islam. Pen and Sword. ISBN 9781848846128.

- Foss, Clive (1975). The Persians in Asia Minor and the End of Antiquity. Vol. 90. Oxford University Press. pp. 721–47. doi:10.1093/ehr/XC.CCCLVII.721.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) (يتطلب اشتراك) - Frye, Richard Nelson (1984). The History of Ancient Iran. C.H.Beck. pp. 1–411. ISBN 9783406093975. قالب:Free access

- Oman, Charles (1893). Europe, 476-918, Volume 1. Macmillan. قالب:Free access

- Potts, Daniel T. (2014). Nomadism in Iran: From Antiquity to the Modern Era. London and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 1–558. ISBN 9780199330799.

- Rawlinson, George (2004). The Seven Great Monarchies of the Ancient Eastern World. Gorgias Press LLC. ISBN 9781593331719. قالب:Free access

- Shahbazi, A. Shapur (2005). "Sasanian dynasty". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Online Edition.

هرمز الرابع

| ||

| سبقه كسرى الأول |

شاهنشاه إيران وآنيران 579–590 |

تبعه بهرام تشوبين (ملك منافس) كسرى الثاني (خليفة) |

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing Middle Persian-language text

- Articles containing فارسية-language text

- CS1 maint: location missing publisher

- CS1 errors: periodical ignored

- صفحات تحتوي روابط لمحتوى للمشتركين فقط

- مواليد 540

- ساسانيون

- وفيات 590

- ملوك فرس مغتالون

- ملوك القرن السادس في الشرق الأوسط

- ملوك مقتولون

- أشخاص من الحروب الرومانية الفارسية

- 6th-century Sasanian monarchs

- شخصيات الشاهنامه

- 6th-century murdered monarchs

- Hormizd IV