نترات الپوتاسيوم

| |||

|

| |||

| الأسماء | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| اسم أيوپاك

Potassium nitrate

| |||

| أسماء أخرى

Saltpetre

Nitrate of potash | |||

| Identifiers | |||

| رقم CAS | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.028.926 | ||

| رقم EC |

| ||

| E number | E252 (preservatives) | ||

| KEGG | |||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| رقم RTECS |

| ||

| UNII | |||

| UN number | 1486 | ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| InChI | InChI={{{value}}} | ||

| SMILES | |||

| الخصائص | |||

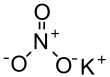

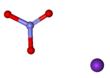

| الصيغة الجزيئية | KNO3 | ||

| كتلة مولية | 101.1032 g/mol | ||

| المظهر | white solid | ||

| الرائحة | odorless | ||

| الكثافة | 2.109 g/cm3 (16 °C) | ||

| نقطة الانصهار | |||

| نقطة الغليان | |||

| قابلية الذوبان في الماء | 133 g/L (0 °C) 316 g/L (20 °C) 2460 g/L (100 °C)[2] | ||

| قابلية الذوبان | slightly soluble in ethanol soluble in glycerol, ammonia | ||

| القاعدية (pKb) | 15.3[3] | ||

| معامل الانكسار (nD) | 1.5056 | ||

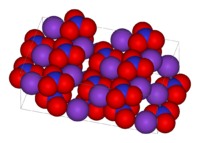

| البنية | |||

| البنية البلورية | Orthorhombic, Aragonite | ||

| الكيمياء الحرارية | |||

| الإنتالپية المعيارية للتشكل ΔfH |

-494.00 kJ/mol | ||

| سعة الحرارة النوعية، C | 95.06 J/mol K | ||

| المخاطر | |||

| خطر رئيسي | Oxidant, Harmful if swallowed, Inhaled, or absorbed on skin. Causes Irritation to Skin and Eye area. | ||

تبويب الاتحاد الاوروپي (DSD)

|

Oxidant (O) | ||

| توصيف المخاطر | R8 R22 R36 R37 R38 | ||

| تحذيرات وقائية | S7 S16 S17 S26 S36 S41 | ||

| NFPA 704 (معيـَّن النار) | |||

| نقطة الوميض | Non-flammable | ||

| الجرعة أو التركيز القاتل (LD, LC): | |||

LD50 (الجرعة الوسطى)

|

3750 mg/kg | ||

| مركبات ذا علاقة | |||

أنيونات أخرى

|

Potassium nitrite | ||

كاتيونات أخرى

|

Lithium nitrate Sodium nitrate Rubidium nitrate Caesium nitrate | ||

ما لم يُذكر غير ذلك، البيانات المعطاة للمواد في حالاتهم العيارية (عند 25 °س [77 °ف]، 100 kPa). | |||

| مراجع الجدول | |||

نترات البوتاسيوم (KNO3) هي مادة كيميائية تتكون من البوتاسيوم والنيتروجين والأكسجين وتعتبر مادة مساعدة على الإشتعال لأحتوائها على ثلاث ذرات أكسجين وتدخل في تركيب البارود كما انها متوفرة في الأسواق كسماد غني بالنيتروجين. تتواجد هذه المادة في الطبيعة ويمكن استخلاصها عبر تذويب تربة غنية بهذا الملح (نيترات البوتاسيوم) في الماء ثم تبريد المحلول لتترسب بلورات هذه المادة, ويمكن تحضيره صناعيا عبر تفاعل هيدروكسيد البوتاسيوم مع حمض النيتريك.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

تاريخ الانتاج

من المصادر المعدنية

أقدم عملية تنقية كاملة معروفة لنترات البوتاسيوم شرحها في 1270 الكيميائي والمهندس حسن الرماح من بلاد الشام في كتابه الفروسية والمناصب الحربية. في هذا الكتاب، وصف الرماح أول تنقية للبارود (معدن سالتبيتر الخام) بغليه مع أقل قدر من الماء واستخدام فقط المحلول الساخن، ثم استخدام كربونات البوتاسيوم (في شكل رماد الخشب) لإزالة الكالسيوم والمغنسيوم بترسيب كرباناتهما من هذا المحلول، تاركاً محلول نترات البوتاسيوم المنقاة، والتي يمكن تجفيفها.[4] وكان يُستخدم في صناعة البارود والمتفجرات. المصطلح الذي استخدمه الرماح يدل على الأصل الصيني لأسلحة البارود التي كتب عنها.[5] وبينما كانت نترات البوتاسيوم يسميها العرب "الثلج الصيني"، ويسميها الفرس "الملح الصيني".[6][7][8][9][10]

على الأقل حتى عام 1845، كانت رواسب السالتپيتر التشيلي تُستغل في تشيلي وكاليفورنيا، الولايات المتحدة.

من الكهوف

من أهم المصادر الطبيعية لنترات الپوتاسيوم بلورة الودائع من جدران الكهوف وتركامات ذرق الطيور في الكهوف.[11] يتم الاستخراج بغمر الذرق في الماء لمدة يوم، تصفيته، وجمع البلورات من المياه المصفاة. تقليدياً، كان الذرق هو المصدر المستخدم لصناعة البارود لصواريخ بانگ فاي.

لوكونت

لعل أكثر المناقشات استفاضة لإنتاج هذه المادة هي نص لوكونت 1862.[12] كان يكتب لغرض صريح هو زيادة الإنتاج في الولايات الكونفدرالية لدعم احتياجاتها أثناء الحرب الأهلية الأمريكية. حيث أنه كان يدعو لمساعدة التجمعات الزراعية الريفية، كانت الأوصاف والتعليمات بسيطة وصريحة على حد سواء. قام بتفصيل "الطريقة الفرنسية"، مع الكثير من التغييرات، فضلاً عن "الطريقة السويسرية". كان هناك الكثير من الإشارات للطريقة التي تستخدم القش والبول فقط، لكن لم تستخدم مثل هذه الطريقة في هذا العمل.

الطريقة الفرنسية

تجهز مساكب النترات بخلط السماد مع الملاط أو رماد الخشب، المواد الأرضية والعضوية الشائعة مثل القش لمنح المسامية لكومة سماد حجمها تقليدية 1.5×2×5 متر.[12] عادة توضح الكومة تحت المطر، وتبقى مشبعة بالبول، والتي سرعان ما تتحلل في كثير من الأحيان، وأخيراً ترشح بالماء بعد ما يقارب سنة، لإزالة نترات الكالسيوم القابلة للذوبان والتي ستتحول إلى نترات الپوتاسيوم بتصفيتها عبر الپوتاس.

الطريقة السويسرية

يصف لوكونت طريقة استخدام البول فقط وليس الروث، مشيراً إليها بالطريقة السويسرية. يجمع البول مباشرة، في حفر رملية تحت الإسطبل. يحفر الرمل ذاتياً ويسرب النترات التي تتحول فيما بعد إلى نترات الپوتاسيوم عن طريق الپوتاس، على النحو الوارد أعلاه.

من حمض النيتريك

من 1903 حتى فترة الحرب العالمية الأولى، كانت نترات الپوتاسيوم المستخدمة في تصنيع المسحوق الأسود والسماد تنتج على نطاق صناعي من حمض النتريك المنتج بواسطة عملية بيركلاند-إيد، والتي تستخدم القوس الكهربائي لأكسدة النتروجين من الهواء. أثناء الحرب العالمية الأولى عملية هابر التي بدأ استخدامها مؤخراً على النطاق الصناعي (1913) كانت تستخدم مع عملية اوستڤالد بعد عام 1915، مما سمح للألمان بانتاج حمض النتريك من أجل الحرب بعد قطع إمداداتها من نترات الصوديوم من تشيلي (انظر نتريت). عملية هابر تحفز إنتاج الأمونيا من النتروجين الجوي، والهيدروجين المنتج صناعياً. منذ نهاية الحرب العالمية الأولى حتى اليوم، تنتج جميع النترات العضوية بصفة خاصة من جميع نترات الپوتاسيوم تقريباً، المستخدم الآن fine chemical، تنتج من أملاح الپوتاسيوم وحمض النتريك القاعدي.

الانتاج

نترات الپوتاسيوم يمكن صنعها بجمع نترات الأمونيوم وهيدروكسيد الپوتاسيوم.

- NH4NO3 (aq) + KOH (aq) → NH3 (g) + KNO3 (aq) + H2O (l)

الطريقة البديلة لإنتاج نترات الپوتاسيوم بدون منتج جانبي للأمونيا هي الجمع بين نترات الأمونيوم وكلوريد الپوتاسيوم، وجمعه بسهولة كبديل ملح خالي من الصوديوم.

- NH4NO3 (aq) + KCl (aq) → NH4Cl (aq) + KNO3 (aq)

يمكن أيضاً إنتاج نترات الپوتاسيوم بتحييد حمض النتريك مع هيدروكسيد الپوتاسيوم. هذا التفاعل مصدر لحرارة عالية.

- KOH (aq) + HNO3 → KNO3 (aq) + H2O (l)

وعلى النطاق الصناعي، يتم تحضيرها بتفاعل الإحلال المزدوج بين نترات الصوديوم وكلوريد الپوتاسيوم.

- NaNO3 (aq) + KCl (aq) → NaCl (aq) + KNO3 (aq)

الخصائص

لنترات الپوتاسيوم هيكل بلوري معيني قائم عند درجة حرارة الغرفة، والذي يتحول إلى نظام ثلاثي الزوايا عند درجة حرارة 129 °س. عند تسخينه إلى درجات حرارة تتراوح بين 550 و790 °س تحت جو مشبع بالأكسجين، يفقد الأكسجين ويصل إلى درجة حرارة متوازنة مع نيتريت الپوتاسيوم:[13]

- 2 KNO3 → 2 KNO2 + O2

الاستخدامات

Potassium nitrate has a wide variety of uses, largely as a source of nitrate.

انتاج حمض النيتريك

Historically, nitric acid was produced by combining sulfuric acid with nitrates such as saltpeter. In modern times this is reversed: nitrates are produced from nitric acid produced via the Ostwald process.

مؤكسد

The most famous use of potassium nitrate is probably as the oxidizer in blackpowder. From the most ancient times until the late 1880s, blackpowder provided the explosive power for all the world's firearms. After that time, small arms and large artillery increasingly began to depend on cordite, a smokeless powder. Blackpowder remains in use today in black powder rocket motors, but also in combination with other fuels like sugars in "rocket candy". It is also used in fireworks such as smoke bombs.[14] It is also added to cigarettes to maintain an even burn of the tobacco[15] and is used to ensure complete combustion of paper cartridges for cap and ball revolvers.[16] It can also be heated to several hundred degrees to be used for niter bluing, which is less durable than other forms of protective oxidation, but allows for specific and often beautiful coloration of steel parts, such as screws, pins, and other small parts of firearms.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

تجهيز اللحوم

Potassium nitrate has been a common ingredient of salted meat since antiquity[17] or the Middle Ages.[18] The widespread adoption of nitrate use is more recent and is linked to the development of large-scale meat processing.[19] The use of potassium nitrate has been mostly discontinued because of slow and inconsistent results compared to sodium nitrite compounds such as "Prague powder" or pink "curing salt". Even so, potassium nitrate is still used in some food applications, such as salami, dry-cured ham, charcuterie, and (in some countries) in the brine used to make corned beef (sometimes together with sodium nitrite).[20] When used as a food additive in the European Union,[21] the compound is referred to as E252; it is also approved for use as a food additive in the United States[22] and Australia and New Zealand[23] (where it is listed under its INS number 252).[2]

تجهيز الطعام

In West African cuisine, potassium nitrate (saltpetre) is widely used as a thickening agent in soups and stews such as okra soup[24] and isi ewu. It is also used to soften food and reduce cooking time when boiling beans and tough meat. Saltpetre is also an essential ingredient in making special porridges, such as kunun kanwa[25] literally translated from the Hausa language as 'saltpetre porridge'. In the Shetland Islands (UK) it is used in the curing of mutton to make reestit mutton, a local delicacy.[26]

الأسمدة

Potassium nitrate is used in fertilizers as a source of nitrogen and potassium – two of the macronutrients for plants. When used by itself, it has an NPK rating of 13-0-44.[27][28]

علم العقاقير

- Used in some toothpastes for sensitive teeth.[29] Recently, the use of potassium nitrate in toothpastes for treating sensitive teeth has increased.[30][31]

- Used historically to treat asthma.[32] Used in some toothpastes to relieve asthma symptoms.[33]

- Used in Thailand as main ingredient in kidney tablets to relieve the symptoms of cystitis, pyelitis and urethritis.[34]

- Combats high blood pressure and was once used as a hypotensive.[35]

استخدامات أخرى

- Electrolyte in a salt bridge

- Active ingredient of condensed aerosol fire suppression systems. When burned with the free radicals of a fire's flame, it produces potassium carbonate.[36]

- Works as an aluminium cleaner.

- Component (usually about 98%) of some tree stump removal products. It accelerates the natural decomposition of the stump by supplying nitrogen for the fungi attacking the wood of the stump.[37]

- In heat treatment of metals as a medium temperature molten salt bath, usually in combination with sodium nitrite. A similar bath is used to produce a durable blue/black finish typically seen on firearms. Its oxidizing quality, water solubility, and low cost make it an ideal short-term rust inhibitor.[38]

- To induce flowering of mango trees in the Philippines.[39][40]

- Thermal storage medium in power generation systems. Sodium and potassium nitrate salts are stored in a molten state with the solar energy collected by the heliostats at the Gemasolar Thermosolar Plant. Ternary salts, with the addition of calcium nitrate or lithium nitrate, have been found to improve the heat storage capacity in the molten salts.[41]

- As a source of potassium ions for exchange with sodium ions in chemically strengthened glass.

- As an oxidizer in model rocket fuel called Rocket candy.

انظر أيضاً

الهامش

- ^ قالب:GESTIS

- ^ أ ب B. J. Kosanke, B. Sturman, K. Kosanke, I. von Maltitz, T. Shimizu, M. A. Wilson, N. Kubota, C. Jennings-White, D. Chapman (2004). "2". Pyrotechnic Chemistry. Journal of Pyrotechnics. pp. 5–6. ISBN 1-889526-15-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kolthoff, Treatise on Analytical Chemistry, New York, Interscience Encyclopedia, Inc., 1959.

- ^ أحمد ي حسن، Potassium Nitrate in Arabic and Latin Sources, History of Science and Technology in Islam.

- ^ Jack Kelly (2005). Gunpowder: Alchemy, Bombards, and Pyrotechnics: The History of the Explosive that Changed the World. Basic Books. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-465-03722-3.

Around 1240 the Arabs acquired knowledge of saltpeter ("Chinese snow") from the East, perhaps through India. They knew of gunpowder soon afterward. كما تعلموا الألعاب النارية ("الزهور الصينية") والصواريخ الصينية ("الأسهم الصينية"). Arab warriors had acquired fire lances by 1280. Around that same year, a Syrian named حسن الرماح wrote a book that, as he put it, "treat of machines of fire to be used for amusement of for useful purposes." He talked of rockets, fireworks, fire lances, and other incendiaries, using terms that suggested he derived his knowledge from Chinese sources. He gave instructions for the purification of saltpeter and recipes for making different types of gunpowder.

- ^ Peter Watson (2006). Ideas: A History of Thought and Invention, from Fire to Freud. HarperCollins. p. 304. ISBN 978-0-06-093564-1.

The first use of a metal tube in this context was made around 1280 in the wars between the Song and the Mongols, where a new term, chong, was invented to describe the new horror...Like paper, it reached the West via the Muslims, in this case the writings of the Andalusian botanist Ibn al-Baytar, who died in Damascus in 1248. The Arabic term for saltpetre is 'Chinese snow' while the Persian usage is 'Chinese salt'.28

- ^ Cathal J. Nolan (2006). The age of wars of religion, 1000–1650: an encyclopedia of global warfare and civilization. Vol. Volume 1 of Greenwood encyclopedias of modern world wars. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 365. ISBN 0-313-33733-0. Retrieved 2011-11-28.

In either case, there is linguistic evidence of Chinese origins of the technology: في دمشق، أطلق العرب على السالتپيتر المستخدم في صناعة البارود اسم " الثلج الصيني"، بينما في إيران كان يسمى "الملح الصيني". Whatever the migratory route

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Oliver Frederick Gillilan Hogg (1970). Artillery: its origin, heyday, and decline. Archon Books. p. 123.

The Chinese were certainly acquainted with saltpetre, the essential ingredient of gunpowder. They called it Chinese Snow and employed it early in the Christian era in the manufacture of fireworks and rockets.

- ^ Oliver Frederick Gillilan Hogg (1963). English artillery, 1326–1716: being the history of artillery in this country prior to the formation of the Royal Regiment of Artillery. Royal Artillery Institution. p. 42.

The Chinese were certainly acquainted with saltpetre, the essential ingredient of gunpowder. They called it Chinese Snow and employed it early in the Christian era in the manufacture of fireworks and rockets.

- ^ Oliver Frederick Gillilan Hogg (1993). Clubs to cannon: warfare and weapons before the introduction of gunpowder (reprint ed.). Barnes & Noble Books. p. 216. ISBN 1-56619-364-8. Retrieved 2011-11-28.

The Chinese were certainly acquainted with saltpetre, the essential ingredient of gunpowder. They called it Chinese snow and used it early in the Christian era in the manufacture of fireworks and rockets.

- ^ Major George Rains (1861). Notes on Making Saltpetre from the Earth of the Caves. New Orleans, LA: Daily Delta Job Office. p. 14. Retrieved September 13, 2012.

- ^ أ ب Joseph LeConte (1862). Instructions for the Manufacture of Saltpeter. Columbia, S.C.: South Carolina Military Department. p. 14. Retrieved 2007-10-19.

- ^ Eli S. Freeman (1957). "The Kinetics of the Thermal Decomposition of Potassium Nitrate and of the Reaction between Potassium Nitrite and Oxygen". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 79 (4): 838–842. doi:10.1021/ja01561a015.

- ^ Amthyst Galleries, Inc Archived 2008-11-04 at the Wayback Machine. Galleries.com. Retrieved on 2012-03-07.

- ^ Inorganic Additives for the Improvement of Tobacco Archived 2007-11-01 at the Wayback Machine, TobaccoDocuments.org

- ^ Kirst, W.J. (1983). Self Consuming Paper Cartridges for the Percussion Revolver. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Northwest Development Co.

- ^ Binkerd, E. F; Kolari, O. E (1975-01-01). "The history and use of nitrate and nitrite in the curing of meat". Food and Cosmetics Toxicology. 13 (6): 655–661. doi:10.1016/0015-6264(75)90157-1. ISSN 0015-6264. PMID 1107192.

- ^ "Meat Science", University of Wisconsin. uwex.edu.

- ^ Lauer, Klaus (1991). "The history of nitrite in human nutrition: A contribution from German cookery books". Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 44 (3): 261–264. doi:10.1016/0895-4356(91)90037-a. ISSN 0895-4356. PMID 1999685.

- ^ Corned Beef Archived 2008-03-19 at the Wayback Machine, Food Network

- ^ UK Food Standards Agency: "Current EU approved additives and their E Numbers". Archived from the original on 2010-10-07. Retrieved 2011-10-27.

- ^ US Food and Drug Administration: "Listing of Food Additives Status Part II". Archived from the original on 2011-11-08. Retrieved 2011-10-27.

- ^ Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code "Standard 1.2.4 – Labelling of ingredients". Retrieved 2011-10-27.

- ^ "Cook Clean Site Ghanaian Recipe". CookClean Ghana. Archived from the original on 2013-08-28.

- ^ Marcellina Ulunma Okehie-Offoha (1996). Ethnic & cultural diversity in Nigeria. Trenton, N.J.: Africa World Press.

- ^ Brown, Catherine (2011-11-14). A Year In A Scots Kitchen (in الإنجليزية). Neil Wilson Publishing Ltd. ISBN 9781906476847.

- ^ Michigan State University Extension Bulletin E-896: N-P-K Fertilizers Archived 2015-12-24 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hall, William L; Robarge, Wayne P; Meeting, American Chemical Society (2004). Environmental Impact of Fertilizer on Soil and Water. p. 40. ISBN 9780841238114. Archived from the original on 2018-01-27.

- ^ "Sensodyne Toothpaste for Sensitive Teeth". 2008-08-03. Archived from the original on August 7, 2007. Retrieved 2008-08-03.

- ^ Enomoto, K; et al. (2003). "The Effect of Potassium Nitrate and Silica Dentifrice in the Surface of Dentin". Japanese Journal of Conservative Dentistry. 46 (2): 240–247. Archived from the original on 2010-01-11.

- ^ R. Orchardson; D. G. Gillam (2006). "Managing dentin hypersensitivity" (PDF). Journal of the American Dental Association. 137 (7): 990–8, quiz 1028–9. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0321. PMID 16803826. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-07-29.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Orville Harry Brown (1917). Asthma, presenting an exposition of the nonpassive expiration theory. C.V. Mosby company. p. 277.

- ^ Joe Graedon (May 15, 2010). "'Sensitive' toothpaste may help asthma". The Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on September 16, 2011. Retrieved June 18, 2012.

- ^ LOCAL MANUFACTURED DRUG REGISTRATION FOR HUMAN (COMBINE)[dead link]. fda.moph.go.th

- ^ Reichert ET. (1880). "On the physiological action of potassium nitrite". Am. J. Med. Sci. 80: 158–180. doi:10.1097/00000441-188007000-00011.

- ^ Adam Chattaway; Robert G. Dunster; Ralf Gall; David J. Spring. "THE EVALUATION OF NON-PYROTECHNICALLY GENERATED AEROSOLS AS FIRE SUPPRESSANTS" (PDF). United States National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-07-29.

- ^ Stan Roark (February 27, 2008). "Stump Removal for Homeowners". Alabama Cooperative Extension System. Archived from the original on March 23, 2012.

- ^ David E. Turcotte; Frances E. Lockwood (May 8, 2001). "Aqueous corrosion inhibitor Note. This patent cites potassium nitrate as a minor constituent in a complex mix. Since rust is an oxidation product, this statement requires justification". United States Patent. 6,228,283. Archived from the original on January 27, 2018.

- ^ Elizabeth March (June 2008). "The Scientist, the Patent and the Mangoes – Tripling the Mango Yield in the Philippines". WIPO Magazine. United Nations World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). Archived from the original on 25 August 2012.

- ^ "Filipino scientist garners 2011 Dioscoro L. Umali Award". Southeast Asian Regional Center for Graduate Study and Research in Agriculture (SEARCA). Archived from the original on 30 November 2011.

- ^ Juan Ignacio Burgaleta; Santiago Arias; Diego Ramirez. "Gemasolar, The First Tower Thermosolar Commercial Plant With Molten Salt Storage System" (PDF) (Press Release). Torresol Energy. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 March 2012. Retrieved 7 March 2012.

وصلات خارجية

| أملاح وأسترات أيون النترات | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HNO3 | He | ||||||||||||||||||

| LiNO3 | Be(NO3)2 | B(NO3)4− | RONO2 | NO3− NH4NO3 |

O | FNO3 | Ne | ||||||||||||

| NaNO3 | Mg(NO3)2 | Al(NO3)3 | Si | P | S | ClONO2 | Ar | ||||||||||||

| KNO3 | Ca(NO3)2 | Sc(NO3)3 | Ti(NO3)4 | VO(NO3)3 | Cr(NO3)3 | Mn(NO3)2 | Fe(NO3)3 | Co(NO3)2, Co(NO3)3 |

Ni(NO3)2 | Cu(NO3)2 | Zn(NO3)2 | Ga(NO3)3 | Ge | As | Se | Br | Kr | ||

| RbNO3 | Sr(NO3)2 | Y | Zr(NO3)4 | Nb | Mo | Tc | Ru | Rh | Pd(NO3)2 | AgNO3 | Cd(NO3)2 | In | Sn | Sb | Te | I | XeFNO3 | ||

| CsNO3 | Ba(NO3)2 | Hf | Ta | W | Re | Os | Ir | Pt | Au | Hg2(NO3)2, Hg(NO3)2 |

Tl(NO3)3 | Pb(NO3)2 | Bi(NO3)3 | Po | At | Rn | |||

| Fr | Ra | Rf | Db | Sg | Bh | Hs | Mt | Ds | Rg | Cn | Uut | Fl | Uup | Lv | Uus | Uuo | |||

| ↓ | |||||||||||||||||||

| La | Ce(NO3)x | Pr | Nd | Pm | Sm | Eu | Gd | Tb | Dy | Ho | Er | Tm | Yb | Lu | |||||

| Ac | Th | Pa | UO2(NO3)2 | Np | Pu | Am | Cm | Bk | Cf | Es | Fm | Md | No | Lr | |||||

- CS1 errors: extra text: volume

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- Articles with dead external links from July 2019

- Articles with changed EBI identifier

- ECHA InfoCard ID from Wikidata

- E number from Wikidata

- Chemical articles with unknown parameter in Chembox

- Articles containing unverified chemical infoboxes

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- نترات

- مركبات الپوتاسيوم

- أملاح

- مؤكسدات نارية

- مواد حافظة

- أسمدة غير عضوية

- عوامل مؤكسدة