مختبر علوم المريخ

مفهوم عمل فنى

2011 | |

| المشغل | NASA |

|---|---|

| المتعهدون الرئيسيون | Boeing Lockheed Martin |

| نوع المهمة | Rover |

| تاريخ الاقلاع | November 26, 2011 15:02:00.211 UTC (10:02 EST)[1][2] |

| مركبة الإطلاق | Atlas V 541 (AV-028) |

| موقع الإطلاق | Cape Canaveral LC-41[3] |

| مدة المهمة | 668 Martian sols (686 Earth days) |

| COSPAR ID | MARSCILAB |

| صفحة الإنترنت | Mars Science Laboratory |

| الكتلة | 900 kg (2,000 lb)[4] |

| الطاقة | Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator (RTG) |

| Mars landing | |

| التاريخ | August 5, 2012 (planned)[5][6] |

| الإحداثيات | Gale Crater, 4° 36′ 0″ S, 137° 12′ 0″ E (planned landing site) |

| References: [7][8][9][10] | |

مختبر علوم المريخ ( MSL ) هو بعثة أطلقتها الإدارة الوطنية للملاحة الجوية والفضاء (ناسا) بهدف الهبوط وتشغيل روفر يدعى كيوريوسيتى أى (الفضول) على سطح المريخ [11][12] أطلق MSL في 26 نوفمبر 2011 الساعة 10:02 EST[1][2] ومن المقرر هبوط المختبر على سطح المريخ في غيل(فوهة) بين 6 أغسطس و20 أغسطس 2012 [7][8][9][10][13] مختبر علوم المريخ (ناسا) الملقب كيوريوسيتى بعد هبوط أكثر دقة من محاولات سابقة, سوف يساعد على تقييم "فرص المريخ لل سكني أو الحياة أو بمعنى آخر هل المريخ إذا ما كان يمثل بيئة قادرة على دعم الحياة. إنه لن يبحث عن الحياة نفسها. وسيقوم أيضا بتحليل عينات يأخذها من التربة من خلال حفر الصخور(الجيولوجيا) .[14]

وسوف تكون كيوريوسيتى أكبر خمس مرات وتحمل أكثر من عشرة أضعاف من كتلة الأدوات العلمية مثل مستكشف المريخ روفرز (سبيريت) أو المستكشف أوبورشيونيتى.[15] مختبر علوم المريخ MSL كيوريوسيتى أطلق بواسطة الصاروخ أطلس الخامس ڤى 541 ويتوقع أن تعمل لمدة لا تقل عن 1 سنة مريخية (668 المريخ سولز /686 الأرض أيام) كما تم إستكشافها بأوسع مجال أكثر من أي مجموعة أدوات إستكشاف المريخ السابقة.

بعثة المريخ مختبر علوم المريخ هو جزء من برنامج ناسا لاستكشاف المريخ، وهو جهد طويل المدى لاستكشاف المريخ , بإستخدام عربات آلية روبوت ، وهو المشروع الذي يديره مختبر الدفع النفاث ومعهد كاليفورنيا للتكنولوجيا لناسا. وتبلغ التكلفة الاجمالية للمشروع MSL حوالي 2.5 مليار دولار أمريكي.[16]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الأهداف والغايات

مهمة بعثة مختبر علوم المريخ قد قرر لها اربعة اهداف : تحديد ما إذا كانت توجد الحياة على المريخ ,أو ما إذا كانت قد نشأت في أي وقت مضى على المريخ ،و توصيف المناخ على المريخ ، ولتوصيف الجيولوجيا على المريخ والاستعداد لاستكشاف الإنسان . وللمساهمة في تحقيق أهداف العلم الأربعة ، مختبر علوم المريخ حدد له أيضا ثمانية اهداف علمية :[17][18]

- لتحديد التكوين المعدني لسطح المريخ والمناطق القريبة من السطح ومحتواها الجيولوجي.

- تفسير العوامل التي شكلت وحورت السطح الصخرى (الجيولوجي) و التربة .

- تقييم المدى الزمني (أي 4 مليار سنويا) لعمليات تطور الغلاف الجوي للمريخ .

- تحديد الحالة الراهنة، مثل التوزيع ، و الدورة المائية و مستويات ثاني أكسيد الكربون.

- تميز طائفة واسعة من الإشعاع السطحى ، بما في ذلك إشعاع المجرة ، الأشعة الكونية ، بروتون الحدث الشمسي و النيوترونات#عالية الطاقة النيوترونات الثانوية .

التاريخ

وفي أبريل 2008، أفيد أن المشروع سيتكلف 235 مليون دولار، أو 24 ٪، أكثر من الميزانية ، و قدر أن المال سيتم تعويضه حيث يجب أن يأتي من بعثات أخرى لمشروعات ناسا للمريخ.[15] قبل أكتوبر 2008 فإن مختبر علوم المريخ قد أقترب من تجاوز تكلفتة30 ٪.[19][20] واعتبارا من شهر نوفمبر عام 2008 ، تم الانتهاء من وضع الأساس التطويرى، وإن الكثير من الأجهزة والبرمجيات لمختبر علوم المريخ أضحت كاملة والإختبارات مستمرة.[21] يوم 3 ديسمبر 2008 ، أعلنت ناسا تأجيل إطلاق مختبر علوم المريخ حتى خريف العام 2011 بسبب عدم كفاية الوقت للإختبارات.[22] وتم شرح الأسباب الفنية المتعلقة بالميزانية وراء هذا التأخير إلى جماعة علوم الكواكب في اجتماع يناير 2009 في مقر وكالة ناسا.[23][24]

من 23-29 مارس 2009 ، وكان الجمهور لديه فرصة لإختيار تسعة أسماء من المرشحين النهائيين من خلال استطلاع للرأي العام على موقع وكالة ناسا كمساهمة إضافية للقضاة للنظر في إختيار اسم روفر MSL [11] في مايو27, 2009اسم الفائز ، وقد تم اختيار الفضول كيروسيتي الذي قدمه في الصف السادس ، كلارا ما ، من ولاية كانساس في مسابقة المقال.[11][12][25][26]

في أواخر يونيو 2010، أكمل المهندسون تركيب معدات التعليق والعجلات على الجسم السيارة المريخية. ست عجلات الروك - التصويب تعليق مشابه لتصميم وجد على سيارة مستكشف المريخ وسيارة باثفايندر المريخية . بدأ المهندسون اختبار نظام التعليق المتكامل الذي سيخدم أيضا جهاز الهبوط للمختبر، على عكس سابقيه .[27]

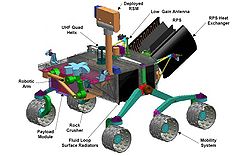

المواصفات الفنية

- "الأبعاد : كيروسيتي روفر هو 10 قدم[convert: unknown unit] في الطول ، ويزن1,984 lb (900 kg) شاملا 176 رطل[convert: unknown unit] الأجهزة العلمية.[15] هو تقريبا في حجم سيارة ميني كوبر .[28] يقارن هذا بمستكشف المريخ روفرز والذى يبلغ طوله 5 أقدام[convert: unknown unit] ويزن 384 رطلا[convert: unknown unit] يشمل 15 رطلا[convert: unknown unit] الأجهزة العلمية.[15][29][30]

- أجهزة الحاسوب: زوجان متماثلان من أجهزة الحاسوب على متن كيروسيتي أطلق عليهما "عنصرالحاسوب" (RCE), يحتوى على ذاكرة تصلب الإشعاع التى تحافظ على تحمل بيئة الإشعاع الشديد من الفضاء وضمان عدم حدوث دورات انقطاع التيار الكهربائي .[31] ذاكرة كل كمبيوتر يتضمن 256 كيلوبايت من إيبروم، 256 ميجابايت و ديناميك رام ، و 2 جيجابايت من ذاكرة فلاش [32] هذا يقارن ب 3 ميغابايت من إيبروم و 128 ميغابايت من ذاكرة ديناميك رام، و 256 ميغابايت من ذاكرة فلاش المستخدمة في مستكشفات المريخ روفرز السابقة.[33]

- مصدر الطاقة: كيوريسيتى يستمد القوة المحركة له من نظير مشع مولد حرارى كهربى (RTG), كما أستخدم في عربات إستكشاف المريخ السابقة بنجاح مثل فايكنج1 و فايكنج2 في عام 1976.[34][35]

- النظائر المشعة وأنظمة الطاقة (RPSs) هى المولدات التي تنتج الكهرباء من الاضمحلال الطبيعي لل البلوتونيوم 238 , وهو من نظائر البلوتونيوم غير الانشطارية . يتم تحويل الحرارة المنبعثة من الاضمحلال الطبيعي لهذا النظير إلى الكهرباء حيث تتوفر الطاقة بإستمرار في جميع الفصول وخلال النهار والليل, و يمكن استخدام النفايات الحرارة الناتجة عبر الأنابيب لأنظمة التدفئة, وجعل الطاقة الكهربائية مخصصة لتشغيل السيارة والمعدات.[34][35] المولد الكهربى بالنظائر المشعة لمستكشف المريخ كيوريسيتى RTGيحتوى على 10.6 رطلا (4.8 كجم) من ثانى أكسيد البلوتونيوم-238

الذى قدمته وزارة الطاقة في الولايات المتحدة .[36]

مولد الطاقة كيوريسيتى هو أحدث جيل من RTG التى قامت ببنائها بوينغ ، ويسمى "المولدات الحرارية بالنظائر المشعة للبعثات متعددة المهام" أوMMRTG .[37]اعتمادا على تكنولوجيا RTG الكلاسيكية، لأنها تمثل خطوة تنموية أكثر مرونة إنضغاطا,[37] وتهدف الى انتاج 125 واط من الطاقة الكهربائية من نحو 2000 واط من الطاقة الحرارية في بداية المهمة.[34][35] إن MMRTG تنتج طاقة أقل مع مرور الوقت حيث يضمحل وقود البلوتونيوم , فإن الحد الأدنى لعمره يقارب 14 عاما ، حيث يصل انتاج الطاقة الكهربائية الى 100 واط.[38][39] مختبر علوم المريخ سيقوم بتوليد 2.5 كيلووات ساعة يوميا مقارنة مع مستكشفات المريخ روفرز والتي يمكن أن تولد حوالي 0.6 كيلو واط ساعة في اليوم الواحد. إن المولدات الحرارية بالنظائر المشعة للبعثات متعددة المهام على متن كيوريسيتى تغذيها 32 من الكريات كل واحدة تماثل حجم حلوى الخطمية .[15]

- أجهزة الكمبيوتر RCE تستخدام المعالج RAD750 وهو يخلف RAD6000 وحدة المعالجة المركزية المستخدمة في مستكشف المريخ روفرز.[40][41] إن المعالج RAD750 قادر على تنفيذ مايقرب من 400 MIPS بينما المعالج RAD6000 كان بإستطاعته تنفيذ ما يقرب من 35 MIPS.[42][43]

- الإتصالات : كيوريسيتى لديه إثنتان من وسائل الاتصال – X-band وهى مرسل ومستقبل يمكن أن يكون التواصل مباشرة مع الأرض ، من خلال UHF إلكترا (الراديو) لايت، برامج الراديو المعرفة مسبقا للتواصل مع بيئة المريخ المدارية. ومن المتوقع أن التواصل مع المدارية أن تكون المساهم الرئيسي في إرجاع البيانات إلى الأرض، لأن كل من يملك طاقة مدارية أكثر وأكبر من طاقة الهوائيات لاندر.[44] في وقت الهبوط سيكون مطلوبا 13 دقيقة، و 46 ثانية للإشارات كى تسافر بين الأرض والمريخ.[45]

- نظم التنقل :على غرار روفرز السابق روفر إستكشاف المريخ و باثفايندر المريخ فإنكيوريسيتى مجهز ب 6 عجلات بنظام التعليق التصويب -الروك . فإن نظام التعليق أيضا يعد بمثابة جهاز الهبوط للسيارة، على عكس سابقيه في أصغر.[27] عجلات كيوريسيتى هي أكبر بكثير من تلك التي استخدمت في روفرز مستكشفات المريخ السابقة . كل عجلة لديها ألية تساعد على تثبيت نمط الجر ولكن أيضا تؤمن الحفاظ على المسارات منقوشة في السطح الرملي للمريخ. ويتم توجيه هذا النظام بإستخدام كاميرات مثبتة تقوم بحساب المسافة المقطوعة. النمط او النظام نفسه هو إشارت مورس "لمختبر الدفع النفاث" (·--- ·--· ·-··).[46]

Wheel size comparison: Sojourner, Mars Exploration Rover, Mars Science Laboratory

The MSL Assembly, Test and Launch Operations (ATLO) in the Jet Propulsion Laboratory

- 120px-Curiosity wheel pattern morse code

Detail of tread with Morse code "JPL"

الحمولة

وقد تم اختيار الأدوات التالية لتطوير أو إنتاج مستكشف المريخ كيروسيتي مختبر علوم المريخ.

- الكاميرات: ماست كام, ماهلى, و ماردى وهى كاميرات قامت بتطويرها نظم مارلين لعلوم الفضاء ,; وكلها تتقاسم عناصر التصميم الشائعة,للمعدات مثل المعدات الإليكترونية على متن السفينة صناديق تجهيز الصور , 1600×1200 CCDs, و RGB باير تصفية الأنماط.< .[47][48][49][50][51][52] المخرج ومبتكر تكنولوجيا كاميرا ثلاثية الأبعاد 3D[53][54][55] جيمس كاميرون شارك في أعمال التصميم في وقت مبكر من كام الماست أو الكاميرا الرئيسية.[56] إمكانية الزوم أو التكبير للكاميرا لم يمكن إدراجها في التصميم النهائى بسبب أن الوقت اللازم لاختبار التكنولوجيا الجديدة بدا متعارضا مع موعد الإطلاق والذى كان يلوح في الأفق في نوفمبر 2011 .[57]

- MastCam : هذا النظام سيوفر أطياف متعددة و اللون الحقيقي مع اثنين من كاميرات التصوير.[48] يمكن للكاميرات التقاط صور اللون الحقيقي بدقة 1600 × 1200 بكسل ويصل إلى 10 لقطة في الثانية الأجهزة مضغوط ، الفيديو عالي الجودة بدقة 720P (1280 × 720).[48] وسوف تكون كاميرا واحدة للتصوير زاوية متوسطة (MAC ماك وهى تمتلك 34 مم البعد البؤري, و 15-درجة مجال الرؤية , وتعطى 22 سم/بيكسل مقياس عند 1 كم.[48] سوف تكون كاميرا أخرى للتصوير زاوية ضيقة (NAC) التي لديها 100 مم البعد البؤرى, 5.1-درجة مجال الرؤية, و تستطيع أن تعطى 7.4 سم/بيكسل مقياس عند 1 كم.[48] مالين أيضا تطور زوج من Mastcams مع عدسة التكبير، والتي قد تختارها وكالة ناسا بدلا من الكاميرات ذات الطول البؤري الثابت.[58] Each camera will have 8 GB of flash memory, which is capable of storing over 5,500 raw images, and can apply real time lossless or JPEG compression.[48] The cameras have an autofocus capability which allows them to focus on objects from 2.1 m (6 ft 11 in) to infinity.[51] Each camera will also have a RGB Bayer pattern filter with 8 filter positions.[48] In comparison to the 1024×1024 black and white panoramic cameras used on the Mars Exploration Rover (MER), the MAC MastCam will have 1.25× higher spatial resolution and the NAC MastCam will have 3.67× higher spatial resolution.[51]

- Mars Hand Lens Imager (MAHLI): This system will consist of a camera mounted to a robotic arm on the rover.[49] It will be used to acquire microscopic images of rock and soil. MAHLI can take true color images at 1600×1200 pixels with a resolution as high as 14.5 micrometers per pixel.[49] MAHLI has a 18.3 mm to 21.3 mm focal length and a 33.8- to 38.5-degree field of view.[49] MAHLI will have both white and ultraviolet LED illumination for imaging in darkness or imaging fluorescence.[49] MAHLI will also have mechanical focusing in a range from infinite to millimetre distances.[49] MAHLI can store either the raw images or do realtime lossless predictive or JPEG compression.[49]

- MSL Mars Descent Imager (MARDI): During the descent to the Martian surface, MARDI will take color images at 1600×1200 pixels with a 1.3-millisecond exposure time starting at distances of about 3.7 km to near 5 meters from the ground and will take images at a rate of 5 frames per second for about 2 minutes.[50][59] MARDI has a pixel scale of 1.5 meters at 2 km to 1.5 millimeters at 2 meters and has a 90-degree circular field of view.[50] MARDI will have 8 GB of internal buffer memory which is capable of storing over 4,000 raw images.[50] MARDI imaging will allow the mapping of surrounding terrain and the location of landing.[50] JunoCam, for another spacecraft, is based on MARDI.[60]

- ChemCam: ChemCam is a suite of remote sensing instruments, including the first laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy (LIBS) system to be used for planetary science and a remote micro-imager (RMI).[61][62] The LIBS instrument can target a rock or soil sample from up to 7 meters away, vaporizing a small amount of it and then collecting a spectrum of the light emitted by the vaporized rock.[61] An infrared laser with 1067 nm wavelength and a 5 nanosecond pulse will focus on a sub-millimeter spot with a power in excess of 10 megawatts per square millimeter, depositing 14 mJ of energy.[61] Detection of the ball of luminous plasma will be done in the visible and near-UV and near-IR range, between 240 nm and 800 nm.[61] Using the same collection optics, the RMI provides context images of the LIBS analysis spots.[61] The RMI resolves 1 mm objects at 10 m distance, and has a field of view covering 20 cm at that distance.[61] The ChemCam instrument suite is being developed by the Los Alamos National Laboratory and the French CESR laboratory.[61][63][64][65]

- NASA's cost for ChemCam is approximately $10M, including an overrun of about $1.5M,[66] which is less than 1/200th of the total mission costs.[67] The flight model of the Mast Unit was delivered from the French CNES to Los Alamos National Laboratory and was able to deliver the engineering model to JPL in February 2008.[68]

- Alpha-particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS): This device will irradiate samples with alpha particles and map the spectra of X-rays that are re-emitted for determining the elemental composition of samples.[69] The APXS is a form of particle-induced X-ray emission (PIXE), which has previously been used by the Mars Pathfinder and the Mars Exploration Rovers.[69][70] The APXS is being developed by the Canadian Space Agency.[69] MacDonald Dettwiler (MDA), the Canadian aerospace company that build the Canadarm and RADARSAT, will be responsible for the engineering design and building of the APXS. The APXS science team includes members from the University of Guelph, the University of New Brunswick, the University of Western Ontario, NASA, the University of California, San Diego and Cornell University.[بحاجة لمصدر]

- CheMin: CheMin stands for "Chemistry and Mineralogy" and is a X-Ray diffraction instrument[71] that will quantify minerals and mineral structure of samples.[71] It is being developed by David Blake at NASA Ames Research Center and the NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory.[71][72]

- Sample analysis at Mars (SAM): The SAM instrument suite will analyze organics and gases from both atmospheric and solid samples.[73][74] It is being developed by the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, the Laboratoire Inter-Universitaire des Systèmes Atmosphériques (LISA) of France's CNRS and Honeybee Robotics, along with many additional external partners.[73][75][76] The SAM suite consists of three instruments:

- The Quadrupole Mass Spectrometer (QMS) will detect gases sampled from the atmosphere or those released from solid samples by heating.[73]

- The Gas Chromatograph (GC) will be used to separate out individual gases from a complex mixture into molecular components with a mass range of 2–235 u.[73]

- The Tunable Laser Spectrometer (TLS) will perform precision measurements of oxygen and carbon isotope ratios in carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4) in the atmosphere of Mars in order to distinguish between a geochemical and a biological origin.[73][76][77][78]

- The SAM also has three subsystems: The chemical separation and processing laboratory (CSPL), for enrichment and derivatization of the organic molecules of the sample; the sample manipulation system (SMS) for transporting powder delivered from the MSL drill to a SAM inlet and into one of 74 sample cups.[73] The SMS then moves the sample to the SAM oven to release gases by heating to up to 1000 oC;[73][79] and the wide range pumps (WRP) subsystem to purge the QMS, TLS, and the CPSL.

- Radiation assessment detector (RAD): This instrument will characterize the broad spectrum of radiation found near the surface of Mars for purposes of determining the viability and shielding needs for human explorers.[80] Funded by the Exploration Systems Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters and the German space agency, DLR, RAD was developed by Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) and the extraterrestrial physics group at Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel, Germany.[80]

- Dynamic albedo of neutrons (DAN): A pulsed neutron source and detector for measuring hydrogen or ice and water at or near the Martian surface, provided by the Russian Federal Space Agency.[81][82]

- Rover environmental monitoring station (REMS): Meteorological package and an ultraviolet sensor provided by the Spanish Ministry of Education and Science, with Finnish Meteorological Institute as a partner.[83][84] It will be mounted on the camera mast and measure atmospheric pressure, humidity, wind currents and direction, air and ground temperature and ultraviolet radiation levels. REMS has been designed to record six atmospheric parameters: wind speed/direction, pressure, relative humidity, air temperature, ground temperature, and ultraviolet radiation. All sensors are located around three elements: two booms attached to the rover Remote Sensing Mast (RSM), the Ultraviolet Sensor (UVS) assembly located on the rover top deck, and the Instrument Control Unit (ICU) inside the rover body. REMS will provide new clues about signature of the Martian general circulation, microscale weather systems, local hydrological cycle, destructive potential of UV radiation, and subsurface habitability based on ground-atmosphere interaction.[83]

- MSL entry descent and landing instrumentation (MEDLI): The MEDLI project’s main objective is to measure aerothermal environments, sub-surface heat shield material response, vehicle orientation, and atmospheric density for the atmospheric entry through the sensible atmosphere down to heat shield separation of the Mars Science Laboratory entry vehicle.[85][86] The MEDLI instrumentation suite will be installed in the heatshield of the MSL entry vehicle.[85][86] The acquired data will support future Mars missions by providing measured atmospheric data to validate Mars atmosphere models and clarify the design margins on future Mars missions.[85][86] MEDLI instrumentation consists of three main subsystems: MEDLI Integrated Sensor Plugs (MISP), Mars Entry Atmospheric Data System (MEADS) and the Sensor Support Electronics (SSE).[85][86]

- Hazard avoidance cameras (Hazcams): The MSL will use two pairs of black and white navigation cameras located on the front left and right and rear left and right of the rover.[87][88] The Hazard Avoidance Cameras (also called Hazcams) are used for autonomous hazard avoidance during rover drives and for safe positioning of the robotic arm on rocks and soils.[87] The cameras will use visible light to capture stereoscopic three-dimensional (3-D) imagery.[87] The cameras have a 120 degree field of view and map the terrain at up to 10 feet (3 meters) in front of the rover.[87] This imagery safeguards against the rover inadvertently crashing into unexpected obstacles, and works in tandem with software that allows the rover to make its own safety choices.[87]

- Navigation cameras (Navcams): The MSL will use a pair of black and white navigation cameras mounted on the mast to support ground navigation.[88][89] The cameras will use visible light to capture stereoscopic 3-D imagery.[89] The cameras have a 45 degree field of view.[89]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Launch vehicle

The MSL was launched from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station Space Launch Complex 41 on November 26, 2011 using the Atlas V 541 provided by United Launch Alliance. This two stage rocket includes a 3.8 m (12 ft) common core booster (CCB) powered by a single RD-180 engine, four solid rocket boosters (SRB), and one Centaur III with a 5.4 m (18 ft) diameter payload fairing. This vehicle is capable of launching up to 17,597 lb (7,982 kg) to geostationary transfer orbit. The Atlas V has also been used to launch the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and the New Horizons probe.[3][90]

The first and second stage along with the solid rocket motors were stacked on October 9, 2011 near the launch pad.[91] The fairing containing MSL was transported to the launch pad on November 3, 2011.[92]

Landing system

Landing a large mass on Mars is a difficult challenge. The atmosphere is thick enough to prevent rockets being used to provide significant deceleration, as flying into the plume at supersonic speed is notoriously unstable.[93] Also, the atmosphere is too thin for parachutes and aerobraking alone to be effective.[93] Although some previous missions have used airbags to cushion the shock of landing, the MSL is too large for this to be an option.

Curiosity will be set down on the Martian surface using a new high-precision entry, descent, and landing (EDL) system that will place it within a 20 km (12 mi) landing ellipse, in contrast to the 150 by 20 km (93 by 12 mi) landing ellipse of the landing systems used by the Mars Exploration Rovers.[94]

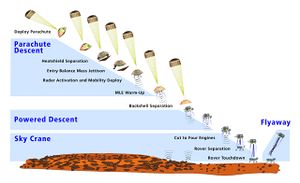

For this, the MSL will employ a combination of several systems in a precise order, where the entry, descent and landing sequence will break down into four parts.[95][96]

- Guided entry: The rover is folded up within an aeroshell which protects it during the travel through space and during the atmospheric entry at Mars. Atmospheric entry is accomplished using a Phenolic Impregnated Carbon Ablator (PICA) heat shield. The 4.5 m (15 ft) diameter heat shield, which will be the largest heat shield ever flown in space,[97] reduces the velocity of the spacecraft by ablation against the Martian atmosphere, from the interplanetary transit velocity of 5.3 to 6 km/s (3.3 to 3.7 mi/s) down to approximately Mach-2, where parachute deployment is possible. Much of the reduction of the landing precision error is accomplished by an entry guidance algorithm, similar to that used by the astronauts returning to Earth in the Apollo space program. This guidance uses the lifting force experienced by the aeroshell to "fly out" any detected error in range and thereby arrive at the targeted landing site. In order for the aeroshell to have lift, its center of mass is offset from the axial centerline which results in an off-center trim angle in atmospheric flight, again similar to the Apollo Command Module. This is accomplished by a series of ejectable ballast masses. The lift vector is controlled by four sets of two Reaction Control System (RCS) thrusters that produce approximately 500 N of thrust per pair. This ability to change the pointing of the direction of lift allows the spacecraft to react to the ambient environment, and steer toward the landing zone. Prior to parachute deployment the entry vehicle must first eject the ballast mass such that the center of gravity offset is removed. Parachute will deploy at about 10 km (6.2 mi) altitude at about 470 m/s (1,500 ft/s).[94]

- Parachute descent: When the entry phase is complete and the capsule has slowed to Mach 2 and at about 7 km altitude, the heat shield will separate and fall away. The Mars Science Laboratory will then deploy a supersonic parachute,[94] as was done by previous landers such as Viking, Mars Pathfinder and the Mars Exploration Rovers. In March and April 2009, the parachute for the MSL was tested in the world's largest wind tunnel and passed flight-qualification testing.[98] The parachute has 80 suspension lines, is over 165 feet (50 meters) long, and is about 51 feet (16 meters) in diameter.[98] The parachute is capable of being deployed at Mach 2.2 and can generate up to 289 kN (65,000 pounds) of drag force in the Martian atmosphere.[98] A camera on the bottom of the rover will acquire about 5 frames per second (with resolution of 1600×1200 pixels) below 3.7 km during a period of about 2 minutes until the rover software confirms successful landing.[99]

- Powered descent: Following the parachute braking, at about 1.8 km altitude, still travelling at about 100 m/s, the rover and descent stage drop out of the aeroshell.[94] The descent stage is a platform above the rover with variable thrust mono propellant hydrazine rocket thrusters on arms extending around this platform to slow the descent. Each of the 8 rockets on this stage produce up to 3.1 kN (700 pounds) of thrust and were derived from those used on the Viking landers.[100] Meanwhile, the rover will transform from its stowed flight configuration to a landing configuration while being lowered beneath the descent stage by the "sky crane" system.

- Sky crane: The sky crane system will lower the rover to a soft landing –wheels down– on the surface of Mars.[94] This consists of 3 bridles lowering the rover and an umbilical cable carrying electrical signals between the descent stage and rover. At roughly 7.5 m (25 ft) below the descent stage the sky crane system slows to a halt and the rover touches down. After the rover touches down it waits 2 seconds to confirm that it is on solid ground and fires several pyros (small explosive devices) activating cable cutters on the bridle and umbilical cords to free itself from the descent stage. The descent stage promptly flies away to a crash landing, and the rover gets ready to roam Mars. The planned sky crane powered descent landing system has never been used in actual missions before.[101]

Landing site

Location and characteristics

Based on rankings of the proposed sites by investigators working on the project, the Gale Crater was selected by NASA administrators as the landing site.[8][9][10] Within Gale Crater is a mountain of layered rocks, rising about 5 km (3.1 mi) above the crater floor, that Curiosity will investigate. The landing site (marked by the yellow ellipse in the image) is a smooth region inside the crater in front of the mountain. The landing site is elliptical, 20 by 25 km (12 by 16 mi). Gale Crater diameter is 154 km (96 mi).

The landing site contains material washed down from the wall of the crater, which will provide scientists with the opportunity to investigate the rocks that form the bedrock in this area. The landing ellipse also contains a rock type that is very dense and very bright colored; it is unlike any rock type previously investigated on Mars. It may be an ancient playa lake deposit, and it will likely be the mission's first target in checking for the presence of organic molecules.[بحاجة لمصدر]

However, the area of top scientific interest for Curiosity lies at the base of the mound, just at the edge of the landing ellipse and beyond a dark dune field. Here, orbiting instruments have detected signatures of both clay minerals and sulfate salts[بحاجة لمصدر] . Scientists studying Mars have several hypotheses about how these minerals reflect changes in the Martian environment, particularly changes in the amount of water on the surface of Mars. The rover will use its full instrument suite to study these minerals and how they formed. These rocks are also a prime target in checking for organic molecules, since these environments may have been able to support microbial life.

Two canyons were cut in the mound through the layers containing clay minerals and sulfate salts after deposition of the layers. These canyons expose layers of rock representing tens or hundreds of millions of years of environmental change. Curiosity may be able to investigate these layers in the canyon closest to the landing ellipse, gaining access to a long history of environmental change on the planet. The canyons also contain sediment that was transported by the water that cut the canyons[بحاجة لمصدر] . This sediment interacted with the water, and the environment at that time may have been habitable. Thus, the rocks deposited at the mouth of the canyon closest to the landing ellipse form the third target in the search for organic molecules.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Selection criteria

The essential issue when selecting an optimum landing site is to identify a particular geologic environment, or set of environments, that would support microbial life. To mitigate the risk of disappointment and ensure the greatest chance for science success, interest is placed at the greatest number of possible science objectives at a chosen landing site. Thus, a landing site with morphologic and mineralogic evidence for past water, is better than a site with just one of these criteria. Furthermore, a site with spectra indicating multiple hydrated minerals is preferred; clay minerals and sulfate salts would constitute a rich site. Hematite, other iron oxides, sulfate minerals, silicate minerals, silica, and possibly chloride minerals have all been suggested as possible substrates for fossil preservation. Indeed, all are known to facilitate the preservation of fossil morphologies and molecules on Earth.[102] Difficult terrain is the best candidate for finding evidence of livable conditions, and engineers must be sure the rover can safely reach the site and drive within it.[103]

Current engineering constraints call for a landing site less than 45° from the Martian equator, and less than 1 km above the reference datum.[104] At the first MSL Landing Site workshop, 33 potential landing sites were identified.[105] By the second workshop in late 2007, the list had grown to include almost 50 sites,[106] and by the end of the workshop, the list was reduced to six;[107][108][109] in November 2008, project leaders at a third workshop reduced the list to these four landing sites:[110][111][112][113]

| Name | Location | Elevation | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eberswalde Crater Delta | 23°52′S 326°44′E / 23.86°S 326.73°E | −1,450 metres (−4,760 ft) | Ancient river delta.[114] |

| Holden Crater Fan | 26°22′S 325°06′E / 26.37°S 325.10°E | −1,940 metres (−6,360 ft) | Dry lake bed.[115] |

| Gale Crater | 4°29′S 137°25′E / 4.49°S 137.42°E | −4,451 metres (−2.766 mi) | Features 5 km (3.1 mile) tall mountain of layered material near center.[116] Selected.[10] |

| Mawrth Vallis Site 2 | 24°01′N 341°02′E / 24.01°N 341.03°E | −2,246 metres (−7,369 ft) | Channel carved by catastrophic floods.[117] |

On August 20, 2009, NASA sent out a call for additional landing site proposals and issued another request for proposals on November 16, 2010. A fourth landing site workshop was held in late September 2010.[118] A fifth and final workshop took place during May 16–18, 2011.[119]

On July 22, 2011, it was announced that Gale Crater had been selected as the landing site of the Mars Science Laboratory mission.[7][8][9][10]

انظر أيضاً

الهامش

- ^ أ ب NASA - Mars Science Laboratory, the Next Mars Rover

- ^ أ ب Allard Beutel (19 November 2011). "NASA's Mars Science Laboratory Launch Rescheduled for Nov. 26". NASA. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ^ أ ب Martin, Paul K. "NASA'S MANAGEMENT OF THE MARS SCIENCE LABORATORY PROJECT (IG-11-019)" (PDF). NASA OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL.

- ^ Rover Fast Facts

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةscience-corner - ^ Mars Science Laboratory: Mission Timeline

- ^ أ ب ت خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةlaunch date announcement - ^ أ ب ت ث Webster, Guy; Brown, Dwayne (22 July 2011). "NASA's Next Mars Rover To Land At Gale Crater". NASA JPL. Retrieved 2011-07-22.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Chow, Dennis (22 July 2011). "NASA's Next Mars Rover to Land at Huge Gale Crater". Space.com. Retrieved 2011-07-22.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Amos, Jonathan (22 July 2011). "Mars rover aims for deep crater". BBC News. Retrieved 2011-07-22.

- ^ أ ب ت "Name NASA's Next Mars Rover". NASA/JPL. 2009-05-27. Retrieved 2009-05-27.

- ^ أ ب "NASA Selects Student's Entry as New Mars Rover Name". NASA/JPL. 2009-05-27. Retrieved 2009-05-27.

- ^ "NASA's Shuttle and Rocket Launch Schedule". NASA. 2010-10-27. Retrieved 2010-09-02.

- ^ "Mars Science Laboratory: Mission". NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2010-03-12.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Watson, Traci (2008-04-14). "Troubles parallel ambitions in NASA Mars project". USA Today. Retrieved 2009-05-27.

- ^ Leone, Dan (2011-07-08). "Mars Science Lab Needs $44M More To Fly, NASA Audit Finds". Space News International. Retrieved 2011-11-26.

- ^ "Science Objectives of the MSL". JPL. NASA. Retrieved 2009-05-27.[dead link]

- ^ Mars Science Laboratory Mission Profile

- ^ Frank Morring; Jefferson Morris (October 3, 2008). "Mars Science Lab In Doubt". Aviation Week. Retrieved 2009-05-27.

- ^ Mars Science Laboratory: Still Alive, For Now. October 10, 2008. Universe Today.

- ^ MSL Technical and Replan Status. Richard Cook. (January 9, 2009)

- ^ "Next NASA Mars Mission Rescheduled For 2011". NASA/JPL. December 4, 2008. Retrieved 2008-12-04.

- ^ "Mars Science Laboratory: the budgetary reasons behind its delay". The Space Review. March 2, 2009. Retrieved 2010-01-26.

- ^ "Mars Science Laboratory: the technical reasons behind its delay". The Space Review. March 2, 2009. Retrieved 2010-01-26.

- ^ "NASA Invites Students to Name New Mars Rover". NASA/JPL. November 18, 2008. Retrieved 2009-05-27.

- ^ NASA – Curiosity

- ^ أ ب "Next Mars Rover Sports a Set of New Wheels". NASA/JPL.

- ^ "Nasa committed to Mars rover plan". BBC News. October 11, 2008. Retrieved 2010-05-12.

- ^ Mars Rovers: Pathfinder, MER (Spirit and Opportunity), and MSL (video). Pasadena, California. April 12, 2008. Retrieved September 22, 2011.

- ^ MER Launch Press Kit

- ^ "Mars Science Laboratory Mission Page – Rover "Brains"". Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

- ^ "Mars Science Laboratory: Mission: Rover: Brains". NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2009-03-27.

- ^ Bajracharya, Max (2008). "Autonomy for Mars rovers: past, present, and future". Computer. 41 (12): 45. doi:10.1109/MC.2008.9. ISSN 0018-9162.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ أ ب ت "Multi-Mission Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator" (PDF). NASA/JPL. January 1, 2008. Retrieved 2009-09-07.

- ^ أ ب ت "Mars Exploration: Radioisotope Power and Heating for Mars Surface Exploration" (PDF). NASA/JPL. April 18, 2006. Retrieved 2009-09-07.

- ^ "Mars Science Laboratory Launch Nuclear Safety" (PDF). NASA/JPL/DoE. March 2, 2011. Retrieved 2011-11-28.

- ^ أ ب "Technologies of Broad Benefit: Power". Archived from the original on June 14, 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-20.

- ^ "Mars Science Laboratory – Technologies of Broad Benefit: Power". NASA/JPL. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ Ajay K. Misra (June 26, 2006). "Overview of NASA Program on Development of Radioisotope Power Systems with High Specific Power" (PDF). NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2009-05-12.

- ^ "BAE Systems Computers to Manage Data Processing and Command For Upcoming Satellite Missions" (Press release). BAE Systems. June 17, 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-17.

- ^ "E&ISNow — Media gets closer look at Manassas" (PDF). BAE Systems. August 1, 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-17.[dead link]

- ^ "RAD750 radiation-hardened PowerPC microprocessor" (PDF). BAE Systems. July 1, 2008. Retrieved 2009-09-07.

- ^ "RAD6000 Space Computers" (PDF). BAE Systems. June 23, 2008. Retrieved 2009-09-07.

- ^ Andre Makovsky, Peter Ilott, Jim Taylor (2009). "Mars Science Laboratory Telecommunications System Design" (PDF). JPL.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mars Earth distance in light minutes, Wolfram Alpha

- ^ "New Mars Rover to Feature Morse Code". National Association for Amateur Radio.

- ^ Malin, M. C.; Bell, J. F.; Cameron, J.; Dietrich, W. E.; Edgett, K. S.; Hallet, B.; Herkenhoff, K. E.; Lemmon, M. T.; Parker, T. J. (2005). "The Mast Cameras and Mars Descent Imager (MARDI) for the 2009 Mars Science Laboratory" (PDF). 36th Annual Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. 36: 1214. Bibcode:2005LPI....36.1214M.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ "Mast Camera (Mastcam)". NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2009-03-18.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ "Mars Hand Lens Imager (MAHLI)". NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2009-03-23.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج "Mars Descent Imager (MARDI)". NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2009-04-03.

- ^ أ ب ت "Mars Science Laboratory (MSL): Mast Camera (Mastcam): Instrument Description". Malin Space Science Systems. Retrieved 2009-04-19.

- ^ "Mars Science Laboratory Instrumentation Announcement from Alan Stern and Jim Green, NASA Headquarters". SpaceRef Interactive.

- ^ {{{1}}} patent {{{2}}}

- ^ {{{1}}} patent {{{2}}}

- ^ {{{1}}} patent {{{2}}}

- ^ McCarthy, Erin (August 30, 2010). "James Cameron Designs 3D Camera for Mars Rover". Popular Mechanics.

- ^ David, Leonard (March 28, 2011). "NASA Nixes 3-D Camera for Next Mars Rover". Space.com.

- ^ "Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) Mast Camera (Mastcam)".

- ^ "Mars Descent Imager (MARDI) Update". Malin Space Science Systems. November 12, 2007.

- ^ Malin Space Science Systems – Junocam, Juno Jupiter Orbiter

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ "MSL Science Corner: Chemistry & Camera (ChemCam)". NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2009-09-09.

- ^ Spacecraft: Surface Operations Configuration: Science Instruments: ChemCam

- ^

Salle B., Lacour J. L., Mauchien P., Fichet P., Maurice S., Manhes G. (2006). "Comparative study of different methodologies for quantitative rock analysis by Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy in a simulated Martian atmosphere" (PDF). Spectrochimica Acta Part B-Atomic Spectroscopy. 61 (3): 301–313. Bibcode:2006AcSpe..61..301S. doi:10.1016/j.sab.2006.02.003.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ CESR presentation on the LIBS

- ^ ChemCam fact sheet

- ^ Wiens R.C., Maurice S. (2008). "Corrections and Clarifications, News of the Week". Science. 322 (5907): 1466. doi:10.1126/science.322.5907.1466a. PMID 19056960.

- ^ Wiens R.C., Maurice S. (2008). "ChemCam's Cost a Drop in the Mars Bucket". Science. 322 (5907): 1464. doi:10.1126/science.322.5907.1464a. PMID 19056957.

- ^ ChemCam Status April, 2008

- ^ أ ب ت "MSL Science Corner: Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer (APXS)". NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2009-09-09.

- ^ R. Rieder, R. Gellert, J. Brückner, G. Klingelhöfer, G. Dreibus, A. Yen, S. W. Squyres (2003). "The new Athena alpha particle X-ray spectrometer for the Mars Exploration Rovers". J. Geophysical Research. 108: 8066. Bibcode:2003JGRE..108.8066R. doi:10.1029/2003JE002150.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ أ ب ت "MSL Chemistry & Mineralogy X-ray diffraction(CheMin)". NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2011-11-25.

- ^ Sarrazin P., Blake D., Feldman S., Chipera S., Vaniman D., Bish D. (2005). "Field deployment of a portable X-ray diffraction/X-ray fluorescence instrument on Mars analog terrain". Powder Diffraction. 20 (2): 128–133. Bibcode:2005PDiff..20..128S. doi:10.1154/1.1913719.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ "MSL Science Corner: Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM)". NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2009-09-09.

- ^ Overview of the SAM instrument suite

- ^ Cabane M., Coll P., Szopa C., Israel G., Raulin F., Sternberg R., Mahaffy P., Person A., Rodier C., Navarro-Gonzalez R., Niemann H., Harpold D., Brinckerhoff W. (2004). "Did life exist on Mars? Search for organic and inorganic signatures, one of the goals for "SAM" (sample analysis at Mars)". Source: Mercury, Mars and Saturn Advances in Space Research. 33 (12): 2240–2245.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ أ ب "Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) Instrument Suite". NASA. 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-09.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Tenenbaum, David (June 9, 2008). "Making Sense of Mars Methane". Astrobiology Magazine. Retrieved 2008-10-08.

- ^ Tarsitano, C.G. and Webster, C.R. (2007). "Multilaser Herriott cell for planetary tunable laser spectrometers". Applied Optics. 46 (28): 6923–6935. Bibcode:2007ApOpt..46.6923T. doi:10.1364/AO.46.006923. PMID 17906720.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tom Kennedy; Erik Mumm; Tom Myrick; Seth Frader-Thompson. "Optimization of a mars sample manipulation system through concentrated functionality" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ أ ب "SwRI Radiation Assessment Detector (RAD) Homepage". Southwest Research Institute. Retrieved 2011-01-19.

- ^ "MSL Science Corner: Dynamic Albedo of Neutrons (DAN)". NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2009-09-09.

- ^ Litvak, M.L.; Mitrofanov, I.G.; Barmakov, Yu.N.; Behar, A.; Bitulev, A.; Bobrovnitsky, Yu.; Bogolubov, E.P.; Boynton, W.V.; Bragin, S.I. (2008). "The Dynamic Albedo of Neutrons (DAN) Experiment for NASA's 2009 Mars Science Laboratory". Astrobiology. 8 (3): 605–12. doi:10.1089/ast.2007.0157. PMID 18598140.

- ^ أ ب "MSL Science Corner: Rover Environmental Monitoring Station (REMS)". NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2009-09-09.

- ^ "Mars Science Laboratory Fact Sheet" (PDF). NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2011-06-20.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Michael Wright (May 1, 2007). "Science Overview System Design Review (SDR)" (PDF). NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2009-09-09.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Michael Wright (May 1, 2007). "Science Overview System Design Review (SDR)" (PDF). NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2009-09-09.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج "Mars Science Laboratory: Mission: Rover: Eyes and Other Senses: Four Engineering Hazcams (Hazard Avoidance Cameras)". NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2009-04-04.

- ^ أ ب "Mars Science Laboratory Rover in the JPL Mars Yard". NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2009-05-10.

- ^ "Mars Science Laboratory: Mission: Launch Vehicle". NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2009-04-01.

- ^ Assembling Curiosity’s Rocket to Mars

- ^ Sutton, Jane (November 3, 2011). "NASA's new Mars rover reaches Florida launch pad". Reuters.

- ^ أ ب "The Mars Landing Approach: Getting Large Payloads to the Surface of the Red Planet". Universe Today. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج "Final Minutes of Curiosity's Arrival at Mars". NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2011-04-08.

- ^ "Mission Timeline: Entry, Descent, and Landing". NASA and JPL. Archived from the original on June 19, 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-07.

- ^ "Mars Science Laboratory Entry, Descent, and Landing Triggers". IEEE. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ NASA, Large Heat Shield for Mars Science Laboratory, July 10, 2009 (accessed Mar 26, 2010)

- ^ أ ب ت "Mars Science Laboratory Parachute Qualification Testing". NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2009-04-15.

- ^ "Mars Descent Imager (MARDI)". NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2009-12-02.

- ^ "Aerojet Ships Propulsion for Mars Science Laboratory". Aerojet. Retrieved 2010-12-18.

- ^ Sky crane concept video

- ^ "MSL — Landing Sites Workshop" (Microsoft Word). July 15.

{{cite journal}}:|contribution=ignored (help);|format=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Survivor: Mars — Seven Possible MSL Landing Sites". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. NASA. September 18, 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-21.[dead link]

- ^ "MSL Workshop Summary" (PDF). April 27, 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-29.

- ^ "MSL Landing Site Selection User's Guide to Engineering Constraints" (PDF). June 12, 2006. Retrieved 2007-05-29.

- ^ "Second MSL Landing Site Workshop".

- ^ "MSL Workshop Voting Chart" (PDF). September 18, 2008.

- ^ GuyMac (January 4, 2008). "Reconnaissance of MSL Sites". HiBlog. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

- ^ "Mars Exploration Science Monthly Newsletter" (PDF). August 1, 2008.

- ^ "Site List Narrows For NASA's Next Mars Landing". MarsToday. November 19, 2008. Retrieved 2009-04-21.

- ^ "Current MSL Landing Sites". NASA. Retrieved 2010-01-04.

- ^ "Looking at Landing Sites for the Mars Science Laboratory". YouTube. NASA/JPL. May 27, 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-28.

- ^ "Final 7 Prospective Landing Sites". NASA. February 19, 2009. Retrieved 2009-02-09.

- ^ Mars Science Laboratory: Possible MSL Landing Site: Eberswalde Crater

- ^ Mars Science Laboratory: Possible MSL Landing Site: Holden Crater

- ^ Mars Science Laboratory: Possible MSL Landing Site: Gale Crater

- ^ Mars Science Laboratory: Possible MSL Landing Site: Mawrth Vallis

- ^ Presentations for the Fourth MSL Landing Site Workshop September 2010

- ^ Second Announcement for the Final MSL Landing Site Workshop and Call for Papers March 2011

للاستزادة

M. K. Lockwood (2006). "Introduction: Mars Science Laboratory: The Next Generation of Mars Landers And The Following 13 articles" (.PDF). Journal of Spacecraft and Rockets. 43 (2): 257–257. Bibcode:2006JSpRo..43..257L. doi:10.2514/1.20678.

وصلات خارجية

- MSL Home Page

- MSL – Actual Launch (10:02 am EST/usa, November 26, 2011 – Recorded Video (04:00)

- MSL – Mission Summary – Animated/Extended Video (11:20)

- MSL – Entry, Descent & Landing (EDL) – Animated Video (02:00)

- MSL – Gale Crater Landing Site – Animated/Narrated Video (02:37)

- MSL – NASA/JPL News Channel Videos

- MSL – NASA/JPL Virtual Tour – Rover

- MSL – Construction – Recorded Video

- MSL – Demo, reported by The Planetary Society.

- MSL – Entry, Descent & Landing (EDL) – Description. (PDF)

- ChemCam Mounted with LIBS for Classifying Carbonate Minerals on Mars (PDF)

- MSL Press Kit

- Spherical panorama of Curiosity in the HPSF at KSC - August 12, 2011

- Spherical panorama of the 'Skycrane' landing system for Curiosity in the HPSF at KSC - August 12, 2011

- Spherical panorama of the Aeroshell for Curiosity in the HPSF at KSC - August 12, 2011

- Mobility systems: Like previous rovers Mars Exploration Rovers and Mars Pathfinder, Curiosity is equipped with 6 wheels in a rocker-bogie suspension. The suspension system will also serve as landing gear for the vehicle, unlike its smaller predecessors.[1] Curiosity's wheels are significantly larger than those used on previous rover. Each wheel has a pattern which helps it maintain traction but also leaves patterned tracks in the sandy surface of Mars. That pattern is used by on-board cameras to judge the distance travelled. The pattern itself is Morse code for "JPL" (·--- ·--· ·-··).[2]

Wheel size comparison: Sojourner, Mars Exploration Rover, Mars Science Laboratory

The MSL Assembly, Test and Launch Operations (ATLO) in the Jet Propulsion Laboratory

Payload

The following instruments have been selected for development or production for the MSL rover Curiosity.

- Cameras: The MastCam, MAHLI, and MARDI cameras were developed by Malin Space Science Systems and they all share common design components, such as on-board electronic imaging processing boxes, 1600×1200 CCDs, and a RGB Bayer pattern filter.[3][4][5][6][7][8] Filmmaker and inventor of 3D camera technology[9][10][11] James Cameron participated in early design work on the MastCam.[12] Zoom capability was not included in the final design because of time required to test the new technology and the looming November 2011 launch date.[13]

- MastCam: This system will provide multiple spectra and true color imaging with two cameras.[4] The cameras can take true color images at 1600×1200 pixels and up to 10 frames per second hardware-compressed, high-definition video at 720p (1280×720).[4] One camera will be the Medium Angle Camera (MAC) which has a 34 mm focal length, a 15-degree field of view, and can yield 22 cm/pixel scale at 1 km.[4] The other camera will be the Narrow Angle Camera (NAC) which has a 100 mm focal length, a 5.1-degree field of view, and can yield 7.4 cm/pixel scale at 1 km.[4] Malin is also developing a pair of Mastcams with zoom lens, which NASA may choose to fly instead of the fixed focal length cameras.[14] Each camera will have 8 GB of flash memory, which is capable of storing over 5,500 raw images, and can apply real time lossless or JPEG compression.[4] The cameras have an autofocus capability which allows them to focus on objects from 2.1 m (6 ft 11 in) to infinity.[7] Each camera will also have a RGB Bayer pattern filter with 8 filter positions.[4] In comparison to the 1024×1024 black and white panoramic cameras used on the Mars Exploration Rover (MER), the MAC MastCam will have 1.25× higher spatial resolution and the NAC MastCam will have 3.67× higher spatial resolution.[7]

- Mars Hand Lens Imager (MAHLI): This system will consist of a camera mounted to a robotic arm on the rover.[5] It will be used to acquire microscopic images of rock and soil. MAHLI can take true color images at 1600×1200 pixels with a resolution as high as 14.5 micrometers per pixel.[5] MAHLI has a 18.3 mm to 21.3 mm focal length and a 33.8- to 38.5-degree field of view.[5] MAHLI will have both white and ultraviolet LED illumination for imaging in darkness or imaging fluorescence.[5] MAHLI will also have mechanical focusing in a range from infinite to millimetre distances.[5] MAHLI can store either the raw images or do realtime lossless predictive or JPEG compression.[5]

- MSL Mars Descent Imager (MARDI): During the descent to the Martian surface, MARDI will take color images at 1600×1200 pixels with a 1.3-millisecond exposure time starting at distances of about 3.7 km to near 5 meters from the ground and will take images at a rate of 5 frames per second for about 2 minutes.[6][15] MARDI has a pixel scale of 1.5 meters at 2 km to 1.5 millimeters at 2 meters and has a 90-degree circular field of view.[6] MARDI will have 8 GB of internal buffer memory which is capable of storing over 4,000 raw images.[6] MARDI imaging will allow the mapping of surrounding terrain and the location of landing.[6] JunoCam, for another spacecraft, is based on MARDI.[16]

- ChemCam: ChemCam is a suite of remote sensing instruments, including the first laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy (LIBS) system to be used for planetary science and a remote micro-imager (RMI).[17][18] The LIBS instrument can target a rock or soil sample from up to 7 meters away, vaporizing a small amount of it and then collecting a spectrum of the light emitted by the vaporized rock.[17] An infrared laser with 1067 nm wavelength and a 5 nanosecond pulse will focus on a sub-millimeter spot with a power in excess of 10 megawatts per square millimeter, depositing 14 mJ of energy.[17] Detection of the ball of luminous plasma will be done in the visible and near-UV and near-IR range, between 240 nm and 800 nm.[17] Using the same collection optics, the RMI provides context images of the LIBS analysis spots.[17] The RMI resolves 1 mm objects at 10 m distance, and has a field of view covering 20 cm at that distance.[17] The ChemCam instrument suite is being developed by the Los Alamos National Laboratory and the French CESR laboratory.[17][19][20][21]

- NASA's cost for ChemCam is approximately $10M, including an overrun of about $1.5M,[22] which is less than 1/200th of the total mission costs.[23] The flight model of the Mast Unit was delivered from the French CNES to Los Alamos National Laboratory and was able to deliver the engineering model to JPL in February 2008.[24]

- Alpha-particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS): This device will irradiate samples with alpha particles and map the spectra of X-rays that are re-emitted for determining the elemental composition of samples.[25] The APXS is a form of particle-induced X-ray emission (PIXE), which has previously been used by the Mars Pathfinder and the Mars Exploration Rovers.[25][26] The APXS is being developed by the Canadian Space Agency.[25] MacDonald Dettwiler (MDA), the Canadian aerospace company that build the Canadarm and RADARSAT, will be responsible for the engineering design and building of the APXS. The APXS science team includes members from the University of Guelph, the University of New Brunswick, the University of Western Ontario, NASA, the University of California, San Diego and Cornell University.[بحاجة لمصدر]

- CheMin: CheMin stands for "Chemistry and Mineralogy" and is a X-Ray diffraction instrument[27] that will quantify minerals and mineral structure of samples.[27] It is being developed by David Blake at NASA Ames Research Center and the NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory.[27][28]

- Sample analysis at Mars (SAM): The SAM instrument suite will analyze organics and gases from both atmospheric and solid samples.[29][30] It is being developed by the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, the Laboratoire Inter-Universitaire des Systèmes Atmosphériques (LISA) of France's CNRS and Honeybee Robotics, along with many additional external partners.[29][31][32] The SAM suite consists of three instruments:

- The Quadrupole Mass Spectrometer (QMS) will detect gases sampled from the atmosphere or those released from solid samples by heating.[29]

- The Gas Chromatograph (GC) will be used to separate out individual gases from a complex mixture into molecular components with a mass range of 2–235 u.[29]

- The Tunable Laser Spectrometer (TLS) will perform precision measurements of oxygen and carbon isotope ratios in carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4) in the atmosphere of Mars in order to distinguish between a geochemical and a biological origin.[29][32][33][34]

- The SAM also has three subsystems: The chemical separation and processing laboratory (CSPL), for enrichment and derivatization of the organic molecules of the sample; the sample manipulation system (SMS) for transporting powder delivered from the MSL drill to a SAM inlet and into one of 74 sample cups.[29] The SMS then moves the sample to the SAM oven to release gases by heating to up to 1000 oC;[29][35] and the wide range pumps (WRP) subsystem to purge the QMS, TLS, and the CPSL.

- Radiation assessment detector (RAD): This instrument will characterize the broad spectrum of radiation found near the surface of Mars for purposes of determining the viability and shielding needs for human explorers.[36] Funded by the Exploration Systems Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters and the German space agency, DLR, RAD was developed by Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) and the extraterrestrial physics group at Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel, Germany.[36]

- Dynamic albedo of neutrons (DAN): A pulsed neutron source and detector for measuring hydrogen or ice and water at or near the Martian surface, provided by the Russian Federal Space Agency.[37][38]

- Rover environmental monitoring station (REMS): Meteorological package and an ultraviolet sensor provided by the Spanish Ministry of Education and Science, with Finnish Meteorological Institute as a partner.[39][40] It will be mounted on the camera mast and measure atmospheric pressure, humidity, wind currents and direction, air and ground temperature and ultraviolet radiation levels. REMS has been designed to record six atmospheric parameters: wind speed/direction, pressure, relative humidity, air temperature, ground temperature, and ultraviolet radiation. All sensors are located around three elements: two booms attached to the rover Remote Sensing Mast (RSM), the Ultraviolet Sensor (UVS) assembly located on the rover top deck, and the Instrument Control Unit (ICU) inside the rover body. REMS will provide new clues about signature of the Martian general circulation, microscale weather systems, local hydrological cycle, destructive potential of UV radiation, and subsurface habitability based on ground-atmosphere interaction.[39]

- MSL entry descent and landing instrumentation (MEDLI): The MEDLI project’s main objective is to measure aerothermal environments, sub-surface heat shield material response, vehicle orientation, and atmospheric density for the atmospheric entry through the sensible atmosphere down to heat shield separation of the Mars Science Laboratory entry vehicle.[41][42] The MEDLI instrumentation suite will be installed in the heatshield of the MSL entry vehicle.[41][42] The acquired data will support future Mars missions by providing measured atmospheric data to validate Mars atmosphere models and clarify the design margins on future Mars missions.[41][42] MEDLI instrumentation consists of three main subsystems: MEDLI Integrated Sensor Plugs (MISP), Mars Entry Atmospheric Data System (MEADS) and the Sensor Support Electronics (SSE).[41][42]

- Hazard avoidance cameras (Hazcams): The MSL will use two pairs of black and white navigation cameras located on the front left and right and rear left and right of the rover.[43][44] The Hazard Avoidance Cameras (also called Hazcams) are used for autonomous hazard avoidance during rover drives and for safe positioning of the robotic arm on rocks and soils.[43] The cameras will use visible light to capture stereoscopic three-dimensional (3-D) imagery.[43] The cameras have a 120 degree field of view and map the terrain at up to 10 feet (3 meters) in front of the rover.[43] This imagery safeguards against the rover inadvertently crashing into unexpected obstacles, and works in tandem with software that allows the rover to make its own safety choices.[43]

- Navigation cameras (Navcams): The MSL will use a pair of black and white navigation cameras mounted on the mast to support ground navigation.[44][45] The cameras will use visible light to capture stereoscopic 3-D imagery.[45] The cameras have a 45 degree field of view.[45]

Launch vehicle

The MSL was launched from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station Space Launch Complex 41 on November 26, 2011 using the Atlas V 541 provided by United Launch Alliance. This two stage rocket includes a 3.8 m (12 ft) common core booster (CCB) powered by a single RD-180 engine, four solid rocket boosters (SRB), and one Centaur III with a 5.4 m (18 ft) diameter payload fairing. This vehicle is capable of launching up to 17,597 lb (7,982 kg) to geostationary transfer orbit. The Atlas V has also been used to launch the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and the New Horizons probe.[46][47]

The first and second stage along with the solid rocket motors were stacked on October 9, 2011 near the launch pad.[48] The fairing containing MSL was transported to the launch pad on November 3, 2011.[49]

Landing system

Landing a large mass on Mars is a difficult challenge. The atmosphere is thick enough to prevent rockets being used to provide significant deceleration, as flying into the plume at supersonic speed is notoriously unstable.[50] Also, the atmosphere is too thin for parachutes and aerobraking alone to be effective.[50] Although some previous missions have used airbags to cushion the shock of landing, the MSL is too large for this to be an option.

Curiosity will be set down on the Martian surface using a new high-precision entry, descent, and landing (EDL) system that will place it within a 20 km (12 mi) landing ellipse, in contrast to the 150 by 20 km (93 by 12 mi) landing ellipse of the landing systems used by the Mars Exploration Rovers.[51]

For this, the MSL will employ a combination of several systems in a precise order, where the entry, descent and landing sequence will break down into four parts.[52][53]

- Guided entry: The rover is folded up within an aeroshell which protects it during the travel through space and during the atmospheric entry at Mars. Atmospheric entry is accomplished using a Phenolic Impregnated Carbon Ablator (PICA) heat shield. The 4.5 m (15 ft) diameter heat shield, which will be the largest heat shield ever flown in space,[54] reduces the velocity of the spacecraft by ablation against the Martian atmosphere, from the interplanetary transit velocity of 5.3 to 6 km/s (3.3 to 3.7 mi/s) down to approximately Mach-2, where parachute deployment is possible. Much of the reduction of the landing precision error is accomplished by an entry guidance algorithm, similar to that used by the astronauts returning to Earth in the Apollo space program. This guidance uses the lifting force experienced by the aeroshell to "fly out" any detected error in range and thereby arrive at the targeted landing site. In order for the aeroshell to have lift, its center of mass is offset from the axial centerline which results in an off-center trim angle in atmospheric flight, again similar to the Apollo Command Module. This is accomplished by a series of ejectable ballast masses. The lift vector is controlled by four sets of two Reaction Control System (RCS) thrusters that produce approximately 500 N of thrust per pair. This ability to change the pointing of the direction of lift allows the spacecraft to react to the ambient environment, and steer toward the landing zone. Prior to parachute deployment the entry vehicle must first eject the ballast mass such that the center of gravity offset is removed. Parachute will deploy at about 10 km (6.2 mi) altitude at about 470 m/s (1,500 ft/s).[51]

- Parachute descent: When the entry phase is complete and the capsule has slowed to Mach 2 and at about 7 km altitude, the heat shield will separate and fall away. The Mars Science Laboratory will then deploy a supersonic parachute,[51] as was done by previous landers such as Viking, Mars Pathfinder and the Mars Exploration Rovers. In March and April 2009, the parachute for the MSL was tested in the world's largest wind tunnel and passed flight-qualification testing.[55] The parachute has 80 suspension lines, is over 165 feet (50 meters) long, and is about 51 feet (16 meters) in diameter.[55] The parachute is capable of being deployed at Mach 2.2 and can generate up to 289 kN (65,000 pounds) of drag force in the Martian atmosphere.[55] A camera on the bottom of the rover will acquire about 5 frames per second (with resolution of 1600×1200 pixels) below 3.7 km during a period of about 2 minutes until the rover software confirms successful landing.[56]

- Powered descent: Following the parachute braking, at about 1.8 km altitude, still travelling at about 100 m/s, the rover and descent stage drop out of the aeroshell.[51] The descent stage is a platform above the rover with variable thrust mono propellant hydrazine rocket thrusters on arms extending around this platform to slow the descent. Each of the 8 rockets on this stage produce up to 3.1 kN (700 pounds) of thrust and were derived from those used on the Viking landers.[57] Meanwhile, the rover will transform from its stowed flight configuration to a landing configuration while being lowered beneath the descent stage by the "sky crane" system.

- Sky crane: The sky crane system will lower the rover to a soft landing –wheels down– on the surface of Mars.[51] This consists of 3 bridles lowering the rover and an umbilical cable carrying electrical signals between the descent stage and rover. At roughly 7.5 m (25 ft) below the descent stage the sky crane system slows to a halt and the rover touches down. After the rover touches down it waits 2 seconds to confirm that it is on solid ground and fires several pyros (small explosive devices) activating cable cutters on the bridle and umbilical cords to free itself from the descent stage. The descent stage promptly flies away to a crash landing, and the rover gets ready to roam Mars. The planned sky crane powered descent landing system has never been used in actual missions before.[58]

Landing site

Location and characteristics

Based on rankings of the proposed sites by investigators working on the project, the Gale Crater was selected by NASA administrators as the landing site.[59][60][61] Within Gale Crater is a mountain of layered rocks, rising about 5 km (3.1 mi) above the crater floor, that Curiosity will investigate. The landing site (marked by the yellow ellipse in the image) is a smooth region inside the crater in front of the mountain. The landing site is elliptical, 20 by 25 km (12 by 16 mi). Gale Crater diameter is 154 km (96 mi).

The landing site contains material washed down from the wall of the crater, which will provide scientists with the opportunity to investigate the rocks that form the bedrock in this area. The landing ellipse also contains a rock type that is very dense and very bright colored; it is unlike any rock type previously investigated on Mars. It may be an ancient playa lake deposit, and it will likely be the mission's first target in checking for the presence of organic molecules.[بحاجة لمصدر]

However, the area of top scientific interest for Curiosity lies at the base of the mound, just at the edge of the landing ellipse and beyond a dark dune field. Here, orbiting instruments have detected signatures of both clay minerals and sulfate salts[بحاجة لمصدر] . Scientists studying Mars have several hypotheses about how these minerals reflect changes in the Martian environment, particularly changes in the amount of water on the surface of Mars. The rover will use its full instrument suite to study these minerals and how they formed. These rocks are also a prime target in checking for organic molecules, since these environments may have been able to support microbial life.

Two canyons were cut in the mound through the layers containing clay minerals and sulfate salts after deposition of the layers. These canyons expose layers of rock representing tens or hundreds of millions of years of environmental change. Curiosity may be able to investigate these layers in the canyon closest to the landing ellipse, gaining access to a long history of environmental change on the planet. The canyons also contain sediment that was transported by the water that cut the canyons[بحاجة لمصدر] . This sediment interacted with the water, and the environment at that time may have been habitable. Thus, the rocks deposited at the mouth of the canyon closest to the landing ellipse form the third target in the search for organic molecules.

Selection criteria

The essential issue when selecting an optimum landing site is to identify a particular geologic environment, or set of environments, that would support microbial life. To mitigate the risk of disappointment and ensure the greatest chance for science success, interest is placed at the greatest number of possible science objectives at a chosen landing site. Thus, a landing site with morphologic and mineralogic evidence for past water, is better than a site with just one of these criteria. Furthermore, a site with spectra indicating multiple hydrated minerals is preferred; clay minerals and sulfate salts would constitute a rich site. Hematite, other iron oxides, sulfate minerals, silicate minerals, silica, and possibly chloride minerals have all been suggested as possible substrates for fossil preservation. Indeed, all are known to facilitate the preservation of fossil morphologies and molecules on Earth.[62] Difficult terrain is the best candidate for finding evidence of livable conditions, and engineers must be sure the rover can safely reach the site and drive within it.[63]

Current engineering constraints call for a landing site less than 45° from the Martian equator, and less than 1 km above the reference datum.[64] At the first MSL Landing Site workshop, 33 potential landing sites were identified.[65] By the second workshop in late 2007, the list had grown to include almost 50 sites,[66] and by the end of the workshop, the list was reduced to six;[67][68][69] in November 2008, project leaders at a third workshop reduced the list to these four landing sites:[70][71][72][73]

| Name | Location | Elevation | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eberswalde Crater Delta | 23°52′S 326°44′E / 23.86°S 326.73°E | −1,450 metres (−4,760 ft) | Ancient river delta.[74] |

| Holden Crater Fan | 26°22′S 325°06′E / 26.37°S 325.10°E | −1,940 metres (−6,360 ft) | Dry lake bed.[75] |

| Gale Crater | 4°29′S 137°25′E / 4.49°S 137.42°E | −4,451 metres (−2.766 mi) | Features 5 km (3.1 mile) tall mountain of layered material near center.[76] Selected.[61] |

| Mawrth Vallis Site 2 | 24°01′N 341°02′E / 24.01°N 341.03°E | −2,246 metres (−7,369 ft) | Channel carved by catastrophic floods.[77] |

On August 20, 2009, NASA sent out a call for additional landing site proposals and issued another request for proposals on November 16, 2010. A fourth landing site workshop was held in late September 2010.[78] A fifth and final workshop took place during May 16–18, 2011.[79]

On July 22, 2011, it was announced that Gale Crater had been selected as the landing site of the Mars Science Laboratory mission.[80][59][60][61]

انظر أيضاً

الهامش

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةnew wheels - ^ "New Mars Rover to Feature Morse Code". National Association for Amateur Radio.

- ^ Malin, M. C.; Bell, J. F.; Cameron, J.; Dietrich, W. E.; Edgett, K. S.; Hallet, B.; Herkenhoff, K. E.; Lemmon, M. T.; Parker, T. J. (2005). "The Mast Cameras and Mars Descent Imager (MARDI) for the 2009 Mars Science Laboratory" (PDF). 36th Annual Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. 36: 1214. Bibcode:2005LPI....36.1214M.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ "Mast Camera (Mastcam)". NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2009-03-18.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ "Mars Hand Lens Imager (MAHLI)". NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2009-03-23.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج "Mars Descent Imager (MARDI)". NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2009-04-03.

- ^ أ ب ت "Mars Science Laboratory (MSL): Mast Camera (Mastcam): Instrument Description". Malin Space Science Systems. Retrieved 2009-04-19.

- ^ "Mars Science Laboratory Instrumentation Announcement from Alan Stern and Jim Green, NASA Headquarters". SpaceRef Interactive.

- ^ {{{1}}} patent {{{2}}}

- ^ {{{1}}} patent {{{2}}}

- ^ {{{1}}} patent {{{2}}}

- ^ McCarthy, Erin (August 30, 2010). "James Cameron Designs 3D Camera for Mars Rover". Popular Mechanics.

- ^ David, Leonard (March 28, 2011). "NASA Nixes 3-D Camera for Next Mars Rover". Space.com.

- ^ "Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) Mast Camera (Mastcam)".

- ^ "Mars Descent Imager (MARDI) Update". Malin Space Science Systems. November 12, 2007.

- ^ Malin Space Science Systems – Junocam, Juno Jupiter Orbiter

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ "MSL Science Corner: Chemistry & Camera (ChemCam)". NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2009-09-09.

- ^ Spacecraft: Surface Operations Configuration: Science Instruments: ChemCam

- ^

Salle B., Lacour J. L., Mauchien P., Fichet P., Maurice S., Manhes G. (2006). "Comparative study of different methodologies for quantitative rock analysis by Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy in a simulated Martian atmosphere" (PDF). Spectrochimica Acta Part B-Atomic Spectroscopy. 61 (3): 301–313. Bibcode:2006AcSpe..61..301S. doi:10.1016/j.sab.2006.02.003.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ CESR presentation on the LIBS

- ^ ChemCam fact sheet

- ^ Wiens R.C., Maurice S. (2008). "Corrections and Clarifications, News of the Week". Science. 322 (5907): 1466. doi:10.1126/science.322.5907.1466a. PMID 19056960.

- ^ Wiens R.C., Maurice S. (2008). "ChemCam's Cost a Drop in the Mars Bucket". Science. 322 (5907): 1464. doi:10.1126/science.322.5907.1464a. PMID 19056957.

- ^ ChemCam Status April, 2008

- ^ أ ب ت "MSL Science Corner: Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer (APXS)". NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2009-09-09.

- ^ R. Rieder, R. Gellert, J. Brückner, G. Klingelhöfer, G. Dreibus, A. Yen, S. W. Squyres (2003). "The new Athena alpha particle X-ray spectrometer for the Mars Exploration Rovers". J. Geophysical Research. 108: 8066. Bibcode:2003JGRE..108.8066R. doi:10.1029/2003JE002150.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ أ ب ت "MSL Chemistry & Mineralogy X-ray diffraction(CheMin)". NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2011-11-25.

- ^ Sarrazin P., Blake D., Feldman S., Chipera S., Vaniman D., Bish D. (2005). "Field deployment of a portable X-ray diffraction/X-ray fluorescence instrument on Mars analog terrain". Powder Diffraction. 20 (2): 128–133. Bibcode:2005PDiff..20..128S. doi:10.1154/1.1913719.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ "MSL Science Corner: Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM)". NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2009-09-09.

- ^ Overview of the SAM instrument suite

- ^ Cabane M., Coll P., Szopa C., Israel G., Raulin F., Sternberg R., Mahaffy P., Person A., Rodier C., Navarro-Gonzalez R., Niemann H., Harpold D., Brinckerhoff W. (2004). "Did life exist on Mars? Search for organic and inorganic signatures, one of the goals for "SAM" (sample analysis at Mars)". Source: Mercury, Mars and Saturn Advances in Space Research. 33 (12): 2240–2245.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ أ ب "Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) Instrument Suite". NASA. 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-09.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Tenenbaum, David (June 9, 2008). "Making Sense of Mars Methane". Astrobiology Magazine. Retrieved 2008-10-08.

- ^ Tarsitano, C.G. and Webster, C.R. (2007). "Multilaser Herriott cell for planetary tunable laser spectrometers". Applied Optics. 46 (28): 6923–6935. Bibcode:2007ApOpt..46.6923T. doi:10.1364/AO.46.006923. PMID 17906720.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tom Kennedy; Erik Mumm; Tom Myrick; Seth Frader-Thompson. "Optimization of a mars sample manipulation system through concentrated functionality" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ أ ب "SwRI Radiation Assessment Detector (RAD) Homepage". Southwest Research Institute. Retrieved 2011-01-19.

- ^ "MSL Science Corner: Dynamic Albedo of Neutrons (DAN)". NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2009-09-09.

- ^ Litvak, M.L.; Mitrofanov, I.G.; Barmakov, Yu.N.; Behar, A.; Bitulev, A.; Bobrovnitsky, Yu.; Bogolubov, E.P.; Boynton, W.V.; Bragin, S.I. (2008). "The Dynamic Albedo of Neutrons (DAN) Experiment for NASA's 2009 Mars Science Laboratory". Astrobiology. 8 (3): 605–12. doi:10.1089/ast.2007.0157. PMID 18598140.

- ^ أ ب "MSL Science Corner: Rover Environmental Monitoring Station (REMS)". NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2009-09-09.

- ^ "Mars Science Laboratory Fact Sheet" (PDF). NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2011-06-20.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Michael Wright (May 1, 2007). "Science Overview System Design Review (SDR)" (PDF). NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2009-09-09.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Michael Wright (May 1, 2007). "Science Overview System Design Review (SDR)" (PDF). NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2009-09-09.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج "Mars Science Laboratory: Mission: Rover: Eyes and Other Senses: Four Engineering Hazcams (Hazard Avoidance Cameras)". NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2009-04-04.

- ^ أ ب "Mars Science Laboratory Rover in the JPL Mars Yard". NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2009-05-10.

- ^ Martin, Paul K. "NASA'S MANAGEMENT OF THE MARS SCIENCE LABORATORY PROJECT (IG-11-019)" (PDF). NASA OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL.

- ^ "Mars Science Laboratory: Mission: Launch Vehicle". NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2009-04-01.

- ^ Assembling Curiosity’s Rocket to Mars

- ^ Sutton, Jane (November 3, 2011). "NASA's new Mars rover reaches Florida launch pad". Reuters.

- ^ أ ب "The Mars Landing Approach: Getting Large Payloads to the Surface of the Red Planet". Universe Today. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج "Final Minutes of Curiosity's Arrival at Mars". NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2011-04-08.

- ^ "Mission Timeline: Entry, Descent, and Landing". NASA and JPL. Archived from the original on June 19, 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-07.

- ^ "Mars Science Laboratory Entry, Descent, and Landing Triggers". IEEE. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ NASA, Large Heat Shield for Mars Science Laboratory, July 10, 2009 (accessed Mar 26, 2010)

- ^ أ ب ت "Mars Science Laboratory Parachute Qualification Testing". NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2009-04-15.

- ^ "Mars Descent Imager (MARDI)". NASA/JPL. Retrieved 2009-12-02.

- ^ "Aerojet Ships Propulsion for Mars Science Laboratory". Aerojet. Retrieved 2010-12-18.

- ^ Sky crane concept video

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةGale Crater - ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةGale Crater2 - ^ أ ب ت ث خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةGale Crater3 - ^ "MSL — Landing Sites Workshop" (Microsoft Word). July 15.

{{cite journal}}:|contribution=ignored (help);|format=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Survivor: Mars — Seven Possible MSL Landing Sites". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. NASA. September 18, 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-21.[dead link]

- ^ "MSL Workshop Summary" (PDF). April 27, 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-29.

- ^ "MSL Landing Site Selection User's Guide to Engineering Constraints" (PDF). June 12, 2006. Retrieved 2007-05-29.

- ^ "Second MSL Landing Site Workshop".

- ^ "MSL Workshop Voting Chart" (PDF). September 18, 2008.

- ^ GuyMac (January 4, 2008). "Reconnaissance of MSL Sites". HiBlog. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

- ^ "Mars Exploration Science Monthly Newsletter" (PDF). August 1, 2008.

- ^ "Site List Narrows For NASA's Next Mars Landing". MarsToday. November 19, 2008. Retrieved 2009-04-21.

- ^ "Current MSL Landing Sites". NASA. Retrieved 2010-01-04.

- ^ "Looking at Landing Sites for the Mars Science Laboratory". YouTube. NASA/JPL. May 27, 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-28.

- ^ "Final 7 Prospective Landing Sites". NASA. February 19, 2009. Retrieved 2009-02-09.

- ^ Mars Science Laboratory: Possible MSL Landing Site: Eberswalde Crater

- ^ Mars Science Laboratory: Possible MSL Landing Site: Holden Crater

- ^ Mars Science Laboratory: Possible MSL Landing Site: Gale Crater

- ^ Mars Science Laboratory: Possible MSL Landing Site: Mawrth Vallis

- ^ Presentations for the Fourth MSL Landing Site Workshop September 2010

- ^ Second Announcement for the Final MSL Landing Site Workshop and Call for Papers March 2011

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةlaunch date announcement

للاستزادة

M. K. Lockwood (2006). "Introduction: Mars Science Laboratory: The Next Generation of Mars Landers And The Following 13 articles" (.PDF). Journal of Spacecraft and Rockets. 43 (2): 257–257. Bibcode:2006JSpRo..43..257L. doi:10.2514/1.20678.

المرئيات

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="http://www.youtube.com/embed/P4boyXQuUIw" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen></iframe>

وصلات خارجية

- MSL Home Page