أولمك

The Olmec heartland, where the Olmec reigned from 1200 to 400 BCE | |

| النطاق الجغرافي | Veracruz, Mexico |

|---|---|

| الفترة | Preclassic Era |

| التواريخ | ح. 1200 – 400 BCE |

| الموقع النمطي | San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán |

| المواقع الرئيسية | La Venta, Tres Zapotes, Laguna de los Cerros |

| سبقها | Archaic Mesoamerica |

| تلاها | Epi-Olmecs |

أولمك Olmecs ( /ˈɒlmɛks,_ˈoʊlʔ/) كانت أول حضارة كبرى معروفة في وسط أمريكا في أعقاب التطور المتقدم في سوكونوسكو. عاش أصحاب حضارة الأولمك في الأراضي الوطيئة الإستوائية بجنوب وسط المكسيك، فيما يعرف اليوم بولايتي ڤيراكروز وتاباسكو. ويعتقد أن حضارة الأولمك مستمدة جزئياً من موكايا وميكسى زوكى المجاورتين.

ازدهرت أولمك أثناء الفترة التكونية لوسط أمريكا، والتي يرجع تاريخها تقريباً من 1500 ق.م. إلى حوالي 400 ق.م. وازدهرت ثقافات ما قبل الأولمك في المنطقة منذ حوالي 2500 سنة ق.م، ولكن بحلول القرن السابع عشر والسادس عشر ق.م، ظهرت ثقافة الأولمك الأولى في موقع سان لورنزو تنوتشتيتلان بالقرب من ساحل جنوب شرق ڤراكروز.[1] وكانت أولى حضارات وسط أمريكا، ووضعت الأساس للعديد من الحضارات التي تلتها.[2] كما يظهر أن الأولمك مارسوا طقوس إراقة الدماء ولعب الكرة الميزوأمريكي، وهو ما وجد في جميع مجتمعات وسط أمريكا الوسطى اللاحقة تقريباً. أهم ما بقي من حضارة الأولمك الآن هو أعمالهم الفنية، وخاصة ما يسمى "الرؤوس الضخمة".[3] تم تحديد حضارة الأولمك أولا من خلال القطع الأثرية اشتراها جامعو التحف في أسواق الآثار التي تعود قبل عصر الاكتشاف في أواخر القرن التاسع عشر وأوائل القرن العشرين. وتعتبر الأعمال الفنية للأولمك بين الأكثر لفتا بين آثار أمريكا القديمة.[4]

التسمية

اسم 'أولمك' مشتق من الكلمة الناواتلية: Ōlmēcatl [oːlˈmeːkat͡ɬ] (المفرد) أو Ōlmēcah [oːlˈmeːkaʔ] (الجمع). هذه الكلمة مؤلفة من مقطعين: ōlli [ˈoːlːi]، وتعني "المطاط"، وmēcatl [ˈmeːkat͡ɬ]، وتعني "الشعب". أي "شعب المطاط".[5][6] The juice of a local vine, Ipomoea alba, was then mixed with this latex to create rubber as early as 1600 BCE.[7] The Nahuatl word for the Olmecs was Ōlmēcatl [oːlˈmeːkat͡ɬ] (singular) or Ōlmēcah [oːlˈmeːkaʔ] (plural). This word is composed of the two words ōlli [ˈoːlːi], meaning "natural rubber", and mēcatl [ˈmeːkat͡ɬ], meaning "people".[8][9]

Early modern explorers and archaeologists, however, mistakenly applied the name "Olmec" to the rediscovered ruins and artifacts in the heartland decades before it was understood that these were not created by the people the Aztecs knew as the "Olmec" but rather a culture that was 2000 years older. Despite the mistaken identity, the name has stuck.[10]

It is not known what name the ancient Olmec used for themselves; some later Mesoamerican accounts seem to refer to the ancient Olmec as "Tamoanchan".[11] A contemporary term sometimes used for the Olmec culture is tenocelome, meaning[مطلوب توضيح] "mouth of the jaguar".[12]

نظرة عامة

The Olmec heartland is the area in the Gulf lowlands where it expanded after early development in Soconusco, Veracruz. This area is characterized by swampy lowlands punctuated by low hills, ridges, and volcanoes. The Sierra de los Tuxtlas rises sharply in the north, along the Gulf of Mexico's Bay of Campeche. Here, the Olmec constructed permanent city-temple complexes at San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán, La Venta, Tres Zapotes, and Laguna de los Cerros. In this region, the first Mesoamerican civilization emerged and reigned from ح. 1400–400 BCE.[13]

الأصول

The beginnings of Olmec civilization have traditionally been placed between 1400 BCE and 1200 BCE. Past finds of Olmec remains ritually deposited at the shrine El Manatí near the triple archaeological sites known collectively as San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán moved this back to "at least" 1600–1500 BCE.[14] It seems that the Olmec had their roots in early farming cultures of Tabasco, which began between 5100 BCE and 4600 BCE. These shared the same basic food crops and technologies of the later Olmec civilization.[15]

What is today called Olmec first appeared fully within San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán, where distinctive Olmec features occurred around 1400 BCE. The rise of civilization was assisted by the local ecology of well-watered alluvial soil, as well as by the transportation network provided by the Coatzacoalcos river basin. This environment may be compared to that of other ancient centers of civilization: the Nile, Indus, and Yellow River valleys and Mesopotamia. This highly productive environment encouraged a densely concentrated population, which in turn triggered the rise of an elite class.[16] The elite class created the demand for the production of the symbolic and sophisticated luxury artifacts that define Olmec culture.[17] Many of these luxury artifacts were made from materials such as jade, obsidian, and magnetite, which came from distant locations and suggest that early Olmec elites had access to an extensive trading network in Mesoamerica. The source of the most valued jade was the Motagua River valley in eastern Guatemala,[18] and Olmec obsidian has been traced to sources in the Guatemala highlands, such as El Chayal and San Martín Jilotepeque, or in Puebla,[19] distances ranging from 200 to 400 km (120–250 miles) away, respectively.[20]

The state of Guerrero, and in particular its early Mezcala culture, seem to have played an important role in the early history of Olmec culture. Olmec-style artifacts tend to appear earlier in some parts of Guerrero than in the Veracruz-Tabasco area. In particular, the relevant objects from the Amuco-Abelino site in Guerrero reveal dates as early as 1530 BCE.[21] The city of Teopantecuanitlan in Guerrero is also relevant in this regard.

لا ڤنتا

The first Olmec center, San Lorenzo, was all but abandoned around 900 BCE at about the same time that La Venta rose to prominence.[22] A wholesale destruction of many San Lorenzo monuments also occurred c. 950s BCE, which may indicate an internal uprising or, less likely, an invasion.[23] The latest thinking, however, is that environmental changes may have been responsible for this shift in Olmec centers, with certain important rivers changing course.[24]

In any case, following the decline of San Lorenzo, La Venta became the most prominent Olmec center, lasting from 900 BCE until its abandonment around 400 BCE.[25] La Venta sustained the Olmec cultural traditions with spectacular displays of power and wealth. The Great Pyramid was the largest Mesoamerican structure of its time. Even today, after 2500 years of erosion, it rises 34 m (112 ft) above the naturally flat landscape.[26] Buried deep within La Venta lay opulent, labor-intensive "offerings" – 1000 tons of smooth serpentine blocks, large mosaic pavements, and at least 48 separate votive offerings of polished jade celts, pottery, figurines, and hematite mirrors.[27]

الأفول

Scholars have yet to determine the cause of the eventual extinction of the Olmec culture. Between 400 and 350 BCE, the population in the eastern half of the Olmec heartland dropped precipitously, and the area was sparsely inhabited until the 19th century.[28] According to archaeologists, this depopulation was probably the result of "very serious environmental changes that rendered the region unsuited for large groups of farmers", in particular changes to the riverine environment that the Olmec depended upon for agriculture, hunting and gathering, and transportation. These changes may have been triggered by tectonic upheavals or subsidence, or the siltation of rivers due to agricultural practices.[29]

One theory for the considerable population drop during the Terminal Formative period is suggested by Santley and colleagues (Santley et al. 1997), who propose the relocation of settlements due to volcanism, instead of extinction. Volcanic eruptions during the Early, Late and Terminal Formative periods would have blanketed the lands and forced the Olmec to move their settlements.[30]

Whatever the cause, within a few hundred years of the abandonment of the last Olmec cities, successor cultures became firmly established. The Tres Zapotes site, on the western edge of the Olmec heartland, continued to be occupied well past 400 BCE, but without the hallmarks of the Olmec culture. This post-Olmec culture, often labeled the Epi-Olmec, has features similar to those found at Izapa, some 550 kilometres (340 mi) to the southeast.[31]

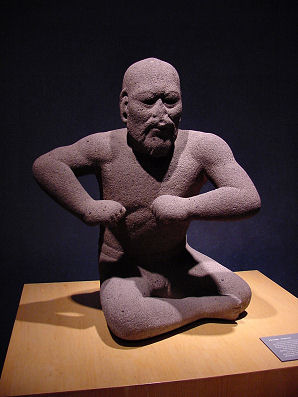

Artifacts

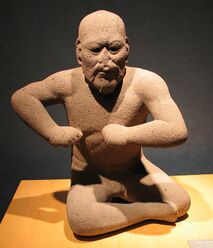

The Olmec culture was first defined as an art style, and this continues to be the hallmark of the culture.[32] Wrought in a large number of media – jade, clay, basalt, and greenstone among others – much Olmec art, such as The Wrestler, is naturalistic. Other art expresses fantastic anthropomorphic creatures, often highly stylized, using an iconography reflective of a religious meaning.[33] Common motifs include downturned mouths and a cleft head, both of which are seen in representations of werejaguars.[32] In addition to making human and human-like subjects, Olmec artisans were adept at animal portrayals.

While Olmec figurines are found abundantly in sites throughout the Formative Period, the stone monuments such as the colossal heads are the most recognizable feature of Olmec culture.[34] These monuments can be divided into four classes:[35]

- Colossal heads (which can be up to 3 m (10 ft) tall);

- Rectangular "altars" (more likely thrones) [36] such as Altar 5 shown below;

- Free-standing in-the-round sculpture, such as the twins from El Azuzul or San Martín Pajapan Monument 1; and

- Stele, such as La Venta Monument 19 above. The stelae form was generally introduced later than the colossal heads, altars, or free-standing sculptures. Over time, the stele changed from simple representation of figures, such as Monument 19 or La Venta Stela 1, toward representations of historical events, particularly acts legitimizing rulers. This trend would culminate in post-Olmec monuments such as La Mojarra Stela 1, which combines images of rulers with script and calendar dates.[37]

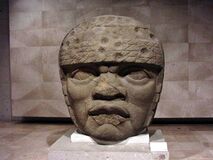

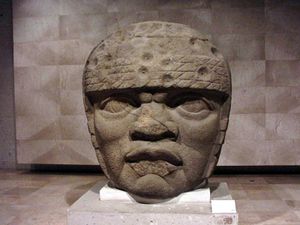

Colossal heads

The most recognized aspect of the Olmec civilization are the enormous helmeted heads.[38] As no known pre-Columbian text explains them, these impressive monuments have been the subject of much speculation. Once theorized to be ballplayers, it is now generally accepted that these heads are portraits of rulers, perhaps dressed as ballplayers.[39] Infused with individuality, no two heads are alike and the helmet-like headdresses are adorned with distinctive elements, suggesting personal or group symbols. Some have also speculated that Mesoamerican people believed that the soul, along with all of one's experiences and emotions, was contained inside the head.[40][41]

Seventeen colossal heads have been unearthed to date.[42]

| Site | Count | Designations |

|---|---|---|

| San Lorenzo | 10 | Colossal Heads 1 through 10 |

| La Venta | 4 | Monuments 1 through 4 |

| Tres Zapotes | 2 | Monuments A & Q |

| Rancho la Cobata | 1 | Monument 1 |

The heads range in size from the Rancho La Cobata head, at 3.4 m (11 ft) high, to the pair at Tres Zapotes, at 1.47 m (4 ft 10 in). Scholars calculate that the largest heads weigh between 25 and 55 tonnes (28 and 61 short tons).[43]

The heads were carved from single blocks or boulders of volcanic basalt, found in the Sierra de los Tuxtlas. The Tres Zapotes heads, for example, were sculpted from basalt found at the summit of Cerro el Vigía, at the western end of the Tuxtlas. The San Lorenzo and La Venta heads, on the other hand, were probably carved from the basalt of Cerro Cintepec, on the southeastern side,[44] perhaps at the nearby Llano del Jicaro workshop, and dragged or floated to their final destination dozens of miles away.[45] It has been estimated that moving a colossal head required the efforts of 1,500 people for three to four months.[20]

Some of the heads, and many other monuments, have been variously mutilated, buried and disinterred, reset in new locations and/or reburied. Some monuments, and at least two heads, were recycled or recarved, but it is not known whether this was simply due to the scarcity of stone or whether these actions had ritual or other connotations. Scholars believe that some mutilation had significance beyond mere destruction, but some scholars still do not rule out internal conflicts or, less likely, invasion as a factor.[46]

The flat-faced, thick-lipped heads have caused some debate due to their resemblance to some African facial characteristics. Based on this comparison, some writers have said that the Olmecs were Africans who had emigrated to the New World.[47] But the vast majority of archaeologists and other Mesoamerican scholars reject claims of pre-Columbian contacts with Africa.[48] Explanations for the facial features of the colossal heads include the possibility that the heads were carved in this manner due to the shallow space allowed on the basalt boulders. Others note that in addition to the broad noses and thick lips, the eyes of the heads often show the epicanthic fold, and that all these characteristics can still be found in modern Mesoamerican Indians. For instance, in the 1940s, the artist/art historian Miguel Covarrubias published a series of photos of Olmec artwork and of the faces of modern Mexican Indians with very similar facial characteristics.[49] The African origin hypothesis assumes that Olmec carving was intended to be a representation of the inhabitants, an assumption that is hard to justify given the full corpus of representation in Olmec carving.[50]

Ivan Van Sertima claimed that the seven braids on the Tres Zapotes head was an Ethiopian hair style, but he offered no evidence it was a contemporary style. The Egyptologist Frank J. Yurco has said that the Olmec braids do not resemble contemporary Egyptian or Nubian braids.[51]

Richard Diehl wrote "There can be no doubt that the heads depict the American Indian physical type still seen on the streets of Soteapan, Acayucan, and other towns in the region."[52]

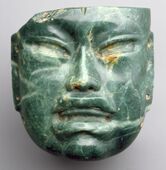

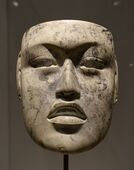

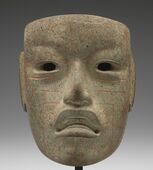

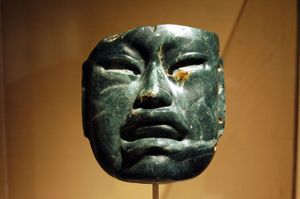

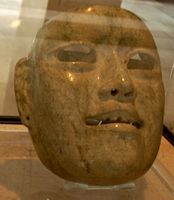

Jade face masks

Another type of artifact is much smaller; hardstone carvings in jade of a face in a mask form. Jade is a particularly precious material, and it was used as a mark of rank by the ruling classes.[53] By 1500 BCE early Olmec sculptors mastered the human form.[40] This can be determined by wooden Olmec sculptures discovered in the swampy bogs of El Manati.[40] Before radiocarbon dating could tell the exact age of Olmec pieces, archaeologists and art historians noticed the unique "Olmec-style" in a variety of artifacts.[40]

Curators and scholars refer to "Olmec-style" face masks but, to date, no example has been recovered in an archaeologically controlled Olmec context. They have been recovered from sites of other cultures, including one deliberately deposited in the ceremonial altepetl (precinct) of Tenochtitlan in what is now Mexico City. The mask would presumably have been about 2000 years old when the Aztecs buried it, suggesting such masks were valued and collected as were Roman antiquities in Europe.[54] The 'Olmec-style' refers to the combination of deep-set eyes, nostrils, and strong, slightly asymmetrical mouth.[40] The "Olmec-style" also very distinctly combines facial features of both humans and jaguars.[55] Olmec arts are strongly tied to the Olmec religion, which prominently featured jaguars.[55] The Olmec people believed that in the distant past a race of werejaguars was made between the union of a jaguar and a woman.[55] One werejaguar quality that can be found is the sharp cleft in the forehead of many supernatural beings in Olmec art. This sharp cleft is associated with the natural indented head of jaguars.[55]

Ornamental mask; 10th century BCE; serpentine; height: 9.2 cm, width: 7.9 cm, depth: 3.2 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Mask; 10th–6th century BCE; jadeite; height: 17.1 cm, width: 16.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Mask; c. 900-500 BCE; jadeite; Dallas Museum of Art (Dallas, Texas, US)

Mask with cinnabar "tattoos"; c. 900-300 BCE; jadeite with cinnabar; Minneapolis Institute of Art (Minneapolis, US)

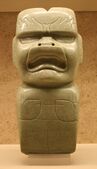

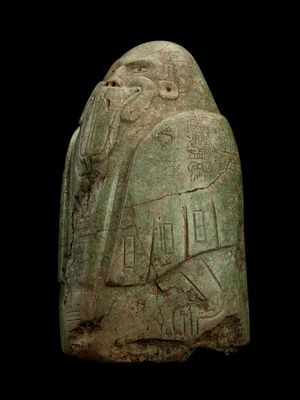

Kunz axes

The Kunz axes (also known as "votive axes") are figures that represent werejaguars and were apparently used for rituals. In most cases, the head is half the total volume of the figure. All Kunz axes have flat noses and an open mouth. The name "Kunz" comes from George Frederick Kunz, an American mineralogist, who described a figure in 1890.[56]

1200-400 BCE; polished green quartz (aventurine); height: 29 cm, width: 13.5 cm; British Museum (London)

900-500 BCE; stone; Dallas Museum of Art (Texas, US)

12th–3rd century BCE; stone; height: 32.2 cm, width: 14 cm, depth: 11.5 cm; Cleveland Museum of Art (Ohio, US)

800-400 BCE; serpentine, cinnabar; Dallas Museum of Art

Beyond the heartland

Olmec-style artifacts, designs, figurines, monuments and iconography have been found in the archaeological records of sites hundreds of kilometres outside the Olmec heartland. These sites include:[57]

Central Mexico

Tlatilco and Tlapacoya, major centers of the Tlatilco culture in the Valley of Mexico, where artifacts include hollow baby-face motif figurines and Olmec designs on ceramics.

Chalcatzingo, in Valley of Morelos, central Mexico, which features Olmec-style monumental art and rock art with Olmec-style figures.

Also, in 2007, archaeologists unearthed Zazacatla, an Olmec-influenced city in Morelos. Located about 40 kilometres (25 mi) south of Mexico City, Zazacatla covered about 2.5 square kilometres (1 sq mi) between 800 and 500 BCE.[58]

Western Mexico

Teopantecuanitlan, in Guerrero, which features Olmec-style monumental art as well as city plans with distinctive Olmec features.

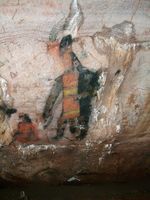

Also, the Juxtlahuaca and Oxtotitlán cave paintings feature Olmec designs and motifs.[59]

Southern Mexico and Guatemala

Olmec influence is also seen at several sites in the Southern Maya area.

In Guatemala, sites showing probable Olmec influence include San Bartolo, Takalik Abaj and La Democracia.

Nature of interaction

Many theories have been advanced to account for the occurrence of Olmec influence far outside the heartland, including long-range trade by Olmec merchants, Olmec colonization of other regions, Olmec artisans travelling to other cities, conscious imitation of Olmec artistic styles by developing towns – some even suggest the prospect of Olmec military domination or that the Olmec iconography was actually developed outside the heartland.[60]

The generally accepted, but by no means unanimous, interpretation is that the Olmec-style artifacts, in all sizes, became associated with elite status and were adopted by non-Olmec Formative Period chieftains in an effort to bolster their status.[61]

الفن

الرؤوس الضخمة

The most recognized aspect of the Olmec civilization are the enormous helmeted heads.[62] As no known pre-Columbian text explains them, these impressive monuments have been the subject of much speculation. Once theorized to be ballplayers, it is now generally accepted that these heads are portraits of rulers, perhaps dressed as ballplayers.[63] Infused with individuality, no two heads are alike and the helmet-like headdresses are adorned with distinctive elements, suggesting personal or group symbols. Some have also speculated that Mesoamerican people believed that the soul, along with all of one's experiences and emotions, was contained inside the head.[40][64]

السبعة عشر رأس الضخمة التي أكتشفت حتى الآن.[65]

الموقع العدد التسمية سان لورنزو 10 الرؤوس الضخمة من 1 إلى 10 لا ڤنتا 4 التماثيل من 1 إلى 4 تريس زاپوتيس 2 الآثار A & Q رانتشو لا كوباتا 1 الأثر رقم 1

The heads range in size from the Rancho La Cobata head, at 3.4 m (11 ft) high, to the pair at Tres Zapotes, at 1.47 m (4 ft 10 in). Scholars calculate that the largest heads weigh between 25 and 55 tonnes (28 and 61 short tons).[66]

The heads were carved from single blocks or boulders of volcanic basalt, found in the Sierra de los Tuxtlas. The Tres Zapotes heads, for example, were sculpted from basalt found at the summit of Cerro el Vigía, at the western end of the Tuxtlas. The San Lorenzo and La Venta heads, on the other hand, were probably carved from the basalt of Cerro Cintepec, on the southeastern side,[67] perhaps at the nearby Llano del Jicaro workshop, and dragged or floated to their final destination dozens of miles away.[68] It has been estimated that moving a colossal head required the efforts of 1,500 people for three to four months.[20]

Some of the heads, and many other monuments, have been variously mutilated, buried and disinterred, reset in new locations and/or reburied. Some monuments, and at least two heads, were recycled or recarved, but it is not known whether this was simply due to the scarcity of stone or whether these actions had ritual or other connotations. Scholars believe that some mutilation had significance beyond mere destruction, but some scholars still do not rule out internal conflicts or, less likely, invasion as a factor.[69]

The flat-faced, thick-lipped heads have caused some debate due to their resemblance to some African facial characteristics. Based on this comparison, some writers have said that the Olmecs were Africans who had emigrated to the New World.[70] But the vast majority of archaeologists and other Mesoamerican scholars reject claims of pre-Columbian contacts with Africa.[71] Explanations for the facial features of the colossal heads include the possibility that the heads were carved in this manner due to the shallow space allowed on the basalt boulders. Others note that in addition to the broad noses and thick lips, the eyes of the heads often show the epicanthic fold, and that all these characteristics can still be found in modern Mesoamerican Indians. For instance, in the 1940s, the artist/art historian Miguel Covarrubias published a series of photos of Olmec artwork and of the faces of modern Mexican Indians with very similar facial characteristics.[72] The African origin hypothesis assumes that Olmec carving was intended to be a representation of the inhabitants, an assumption that is hard to justify given the full corpus of representation in Olmec carving.[73]

Ivan Van Sertima claimed that the seven braids on the Tres Zapotes head was an Ethiopian hair style, but he offered no evidence it was a contemporary style. The Egyptologist Frank J. Yurco has said that the Olmec braids do not resemble contemporary Egyptian or Nubian braids.[74]

Richard Diehl wrote "There can be no doubt that the heads depict the American Indian physical type still seen on the streets of Soteapan, Acayucan, and other towns in the region."[75]

أقنعة الوجه المصنوعة من اليشم

Another type of artifact is much smaller; hardstone carvings in jade of a face in a mask form. Jade is a particularly precious material, and it was used as a mark of rank by the ruling classes.[76] By 1500 BCE early Olmec sculptors mastered the human form.[40] This can be determined by wooden Olmec sculptures discovered in the swampy bogs of El Manati.[40] Before radiocarbon dating could tell the exact age of Olmec pieces, archaeologists and art historians noticed the unique "Olmec-style" in a variety of artifacts.[40]

Curators and scholars refer to "Olmec-style" face masks but, to date, no example has been recovered in an archaeologically controlled Olmec context. They have been recovered from sites of other cultures, including one deliberately deposited in the ceremonial altepetl (precinct) of Tenochtitlan in what is now Mexico City. The mask would presumably have been about 2000 years old when the Aztecs buried it, suggesting such masks were valued and collected as were Roman antiquities in Europe.[77] The 'Olmec-style' refers to the combination of deep-set eyes, nostrils, and strong, slightly asymmetrical mouth.[40] The "Olmec-style" also very distinctly combines facial features of both humans and jaguars.[55] Olmec arts are strongly tied to the Olmec religion, which prominently featured jaguars.[55] The Olmec people believed that in the distant past a race of werejaguars was made between the union of a jaguar and a woman.[55] One werejaguar quality that can be found is the sharp cleft in the forehead of many supernatural beings in Olmec art. This sharp cleft is associated with the natural indented head of jaguars.[55]

Ornamental mask; 10th century BCE; serpentine; height: 9.2 cm, width: 7.9 cm, depth: 3.2 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

قناع مصنوع من اليشم، القرن 10-6 ق.م.؛ الارتفاع 17.1 سم، العرض: 16.5 سم؛ متحف متروپوليتان للفن، مدينة نيويورك.

Mask; c. 900-500 BCE; jadeite; Dallas Museum of Art (Dallas, Texas, US)

Mask with cinnabar "tattoos"; c. 900-300 BCE; jadeite with cinnabar; Minneapolis Institute of Art (Minneapolis, US)

بلطات كونز

The Kunz axes (also known as "votive axes") are figures that represent werejaguars and were apparently used for rituals. In most cases, the head is half the total volume of the figure. All Kunz axes have flat noses and an open mouth. The name "Kunz" comes from George Frederick Kunz, an American mineralogist, who described a figure in 1890.[78]

1200-400 BCE; polished green quartz (aventurine); height: 29 cm, width: 13.5 cm; British Museum (London)

900-500 BCE; stone; Dallas Museum of Art (Texas, US)

12th–3rd century BCE; stone; height: 32.2 cm, width: 14 cm, depth: 11.5 cm; Cleveland Museum of Art (Ohio, US)

800-400 BCE; serpentine, cinnabar; Dallas Museum of Art

ما وراء المعقل

Olmec-style artifacts, designs, figurines, monuments and iconography have been found in the archaeological records of sites hundreds of kilometres outside the Olmec heartland. These sites include:[79]

وسط المكسيك

Tlatilco and Tlapacoya, major centers of the Tlatilco culture in the Valley of Mexico, where artifacts include hollow baby-face motif figurines and Olmec designs on ceramics.

Chalcatzingo, in Valley of Morelos, central Mexico, which features Olmec-style monumental art and rock art with Olmec-style figures.

Also, in 2007, archaeologists unearthed Zazacatla, an Olmec-influenced city in Morelos. Located about 40 kilometres (25 mi) south of Mexico City, Zazacatla covered about 2.5 square kilometres (1 sq mi) between 800 and 500 BCE.[80]

غرب المكسيك

Teopantecuanitlan, in Guerrero, which features Olmec-style monumental art as well as city plans with distinctive Olmec features.

Also, the Juxtlahuaca and Oxtotitlán cave paintings feature Olmec designs and motifs.[81]

جنوب المكسيك وگواتيمالا

Olmec influence is also seen at several sites in the Southern Maya area.

In Guatemala, sites showing probable Olmec influence include San Bartolo, Takalik Abaj and La Democracia.

طبيعة التفاعل

Many theories have been advanced to account for the occurrence of Olmec influence far outside the heartland, including long-range trade by Olmec merchants, Olmec colonization of other regions, Olmec artisans travelling to other cities, conscious imitation of Olmec artistic styles by developing towns – some even suggest the prospect of Olmec military domination or that the Olmec iconography was actually developed outside the heartland.[82]

The generally accepted, but by no means unanimous, interpretation is that the Olmec-style artifacts, in all sizes, became associated with elite status and were adopted by non-Olmec Formative Period chieftains in an effort to bolster their status.[83]

أهم الإبداعات

In addition to their influence with contemporaneous Mesoamerican cultures, as the first civilization in Mesoamerica, the Olmecs are credited, or speculatively credited, with many "firsts", including the bloodletting and perhaps human sacrifice, writing and epigraphy, and the invention of popcorn, zero and the Mesoamerican calendar, and the Mesoamerican ballgame, as well as perhaps the compass.[84] Some researchers, including artist and art historian Miguel Covarrubias, even postulate that the Olmecs formulated the forerunners of many of the later Mesoamerican deities.[85]

إراقة الدماء والتكهن بالقربان

Although the archaeological record does not include explicit representation of Olmec bloodletting,[86] researchers have found other evidence that the Olmec ritually practiced it. For example, numerous natural and ceramic stingray spikes and maguey thorns have been found at Olmec sites,[87] and certain artifacts have been identified as bloodletters.[88]

The argument that the Olmec instituted human sacrifice is significantly more speculative. No Olmec or Olmec-influenced sacrificial artifacts have yet been discovered; no Olmec or Olmec-influenced artwork unambiguously shows sacrificial victims (as do the danzante figures of Monte Albán) or scenes of human sacrifice (such as can be seen in the famous ballcourt mural from El Tajín).[89]

At El Manatí, disarticulated skulls and femurs, as well as the complete skeletons of newborns or fetuses, have been discovered amidst the other offerings, leading to speculation concerning infant sacrifice. Scholars have not determined how the infants met their deaths.[90] Some authors have associated infant sacrifice with Olmec ritual art showing limp werejaguar babies, most famously in La Venta's Altar 5 (on the right) or Las Limas figure.[91] Any definitive answer requires further findings.

الكتابة

The Olmec may have been the first civilization in the Western Hemisphere to develop a writing system. Symbols found in 2002 and 2006 date from 650 BCE[92] and 900 BCE[93] respectively, preceding the oldest Zapotec writing found so far, which dates from about 500 BCE.[94][95]

The 2002 find at the San Andrés site shows a bird, speech scrolls, and glyphs that are similar to the later Maya script.[96] Known as the Cascajal Block, and dated between 1100 and 900 BCE, the 2006 find from a site near San Lorenzo shows a set of 62 symbols, 28 of which are unique, carved on a serpentine block. A large number of prominent archaeologists have hailed this find as the "earliest pre-Columbian writing".[97] Others are skeptical because of the stone's singularity, the fact that it had been removed from any archaeological context, and because it bears no apparent resemblance to any other Mesoamerican writing system.[98]

There are also well-documented later hieroglyphs known as the Isthmian script, and while there are some who believe that the Isthmian may represent a transitional script between an earlier Olmec writing system and the Maya script, the matter remains unsettled.[بحاجة لمصدر]

تقويم العد الطويل الميزوأمريكي واختراع مفهوم الصفر

This is the second oldest Long Count date yet discovered. The numerals 7.16.6.16.18 translate to 3 September 32 BCE (Julian). The glyphs surrounding the date are one of the few surviving examples of Epi-Olmec script.[99]

The Long Count calendar used by many subsequent Mesoamerican civilizations, as well as the concept of zero, may have been devised by the Olmecs. Because the six artifacts with the earliest Long Count calendar dates were all discovered outside the immediate Maya homeland, it is likely that this calendar predated the Maya and was possibly the invention of the Olmecs. Indeed, three of these six artifacts were found within the Olmec heartland. But an argument against an Olmec origin is the fact that the Olmec civilization had ended by the 4th century BCE, several centuries before the earliest known Long Count date artifact.[100]

The Long Count calendar required the use of zero as a place-holder within its vigesimal (base-20) positional numeral system. A shell glyph –![]() – was used as a zero symbol for these Long Count dates, the second oldest of which, on Stela C at Tres Zapotes, has a date of 32 BCE. This is one of the earliest uses of the zero concept in history.[101]

– was used as a zero symbol for these Long Count dates, the second oldest of which, on Stela C at Tres Zapotes, has a date of 32 BCE. This is one of the earliest uses of the zero concept in history.[101]

الديانة والأساطير

Olmec religious activities were performed by a combination of rulers, full-time priests, and shamans. The rulers seem to have been the most important religious figures, with their links to the Olmec deities or supernaturals providing legitimacy for their rule.[102] There is also considerable evidence for shamans in the Olmec archaeological record, particularly in the so-called "transformation figures".[103]

As Olmec mythology has left no documents comparable to the Popol Vuh from Maya mythology, any exposition of Olmec mythology must be based on interpretations of surviving monumental and portable art (such as the Señor de Las Limas statue at the Xalapa Museum), and comparisons with other Mesoamerican mythologies. Olmec art shows that such deities as Feathered Serpent and a rain supernatural were already in the Mesoamerican pantheon in Olmec times.[104]

لعبة الكرة الميزوأمريكية

العرقية واللغة

=التنظيم الاجتماعي والسياسي

التجارة

حياة القرية والنظام الغذائي

تاريخ البحث الأثري

تكهنات بديلة حول الأصول

معرض الصور

"التوأمان" من إل أزوزول، 1200-900 ق.م.

ثلاث سلتات، قطعة طقسية أولمكية.

آنية على طراز الأولمك، عُثر عليها في لاس بوكاس، 1100-800 ق.م.

رسم على طراز الأولمك من كهف جاخوتلاهوسا.

نقش على طراز الأولمك، من تشالكاتزينگو.

انظر أيضاً

- تكهنات بديلة حول أصول الأولمك

- إل أزوزول- موقع أثري صغير في مقل الأولمك

- سيرو دى لاس ميساس - موقع أثري ما قبل الأولمك

- قائمة مواقع المونوليث

- قائمة أهرامات وسط أمريكا

الهوامش

- ^ Diehl, Richard A. (2004). The Olmecs : America's First Civilization. London: Thames and Hudson. pp. 9–25. ISBN 0-500-28503-9.

- ^ See Pool (2007) p. 2. Although there is wide agreement that the Olmec culture helped lay the foundations for the civilizations that followed, there is disagreement over the extent of the Olmec contributions, and even a proper definition of the Olmec "culture". See "Olmec influences on Mesoamerican cultures" for a deeper treatment of this question.

- ^ Diehl, p. 11.

- ^ See Diehl, p. 108 for the "ancient America" superlatives. The artist and archaeologist Miguel Covarrubias (1957) p. 50 says that Olmec pieces are among the world's masterpieces

- ^ Olmecas (n.d.). Think Quest. Retrieved 20 September 2012, from link Archived 24 أكتوبر 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Coe (1968) p. 42

- ^ Rubber Processing, MIT.

- ^ Olmecas (n.d.). Think Quest. Retrieved 20 September 2012, from link Archived 24 أكتوبر 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Coe (1968) p. 42

- ^ Diehl, p. 14.

- ^ Coe (2002) refers to an old Nahuatl poem cited by Miguel Leon-Portilla, which itself refers to a land called "Tamoanchan":

Coe interprets Tamoanchan as a Mayan language word meaning 'Land of Rain or Mist' (p. 61).in a certain era

which no one can reckon

which no one can remember

[where] there was a government for a long time". - ^ The term "tenocelome" is used as early as 1967 by George Kubler in American Anthropologist, v. 69, p. 404.

- ^ Dates from Pool, p. 1. Diehl gives a slightly earlier date of 1500 BCE (p. 9), but the same end-date. Any dates for the start of the Olmec civilization or culture are problematic as its rise was a gradual process. Most Olmec dates are based on radiocarbon dating (see e.g. Diehl, p. 10), which is only accurate within a given range (e.g. ±90 years in the case of early El Manatí layers), and much is still to be learned concerning early Gulf lowland settlements.

- ^ Richard A Diehl, 2004, The Olmecs – America's First Civilization London: Thames & Hudson, pp. 25, 27.

- ^ Diehl, 2004: pp. 23–24.

- ^ Beck, Roger B.; Linda Black; Larry S. Krieger; Phillip C. Naylor; Dahia Ibo Shabaka (1999). World History: Patterns of Interaction. Evanston, IL: McDougal Littell. ISBN 0-395-87274-X.

- ^ Pool, pp. 26–27, provides a great overview of this theory, and says: "The generation of food surpluses is necessary for the development of social and political hierarchies and there is no doubt that high agricultural productivity, combined with the natural abundance of aquatic foods in the Gulf lowlands supported their growth."

- ^ Pool, p. 151.

- ^ Diehl, p. 132, or Pool, p. 150.

- ^ أ ب ت Pool, p. 103.

- ^ Evans, Susan Toby; Webster, David L. (2000). Archaeology of Ancient Mexico and Central America: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. p. 315. ISBN 978-1-136-80185-3.

- ^ Diehl, p. 9.

- ^ Coe (1967), p. 72. Alternatively, the mutilation of these monuments may be unrelated to the decline and abandonment of San Lorenzo. Some researchers believe that the mutilation had ritualistic aspects, particularly since most mutilated monuments were reburied in a row.

- ^ Pool, p. 135. Diehl, pp. 58–59, 82.

- ^ Diehl, p. 9. Pool gives dates 1000 BCE – 400 BCE for La Venta.

- ^ Pool, p. 157.

- ^ Pool, p. 161–162.

- ^ Diehl, p. 82. Nagy, p. 270, however, is more circumspect, stating that in the Grijalva river delta, on the eastern edge of the heartland, "the local population had significantly declined in apparent population density ... A low-density Late Preclassic and Early Classic occupation . . . may have existed; however, it remains invisible."

- ^ Quote and analysis from Diehl, p. 82, echoed in other works such as Pool.

- ^ Vanderwarker (2006) pp. 50–51

- ^ Coe (2002), p. 88.

- ^ أ ب Coe (2002), p. 62.

- ^ Coe (2002), p. 88 and others.

- ^ Pool, p. 105.

- ^ Pool, p. 106. Diehl, pp. 109–115.

- ^ Grove, 1973.

- ^ Pool, pp. 106–108, 176.

- ^ Diehl, p. 111.

- ^ Pool, p. 118; Diehl, p. 112. Coe (2002), p. 69: "They wear headgear rather like American football helmets which probably served as protection in both war and in the ceremonial game played...throughout Mesoamerica."

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر Miller, Mary Ellen. "The Art of Mesoamerica From Olmec to Aztec." Thames & Hudson; 4th edition (20 October 2006).

- ^ Grove, p. 55.

- ^ Pool, p. 107.

- ^ In particular, Williams and Heizer (p. 29) calculated the weight of San Lorenzo Colossal Head 1 at 25.3 short tons, or 23 tonnes. See Scarre. pp. 271–274 for the "55 tonnes" weight.

- ^ See Williams and Heizer for more detail.

- ^ Scarre. Pool, p. 129.

- ^ Diehl, p. 119.

- ^ Wiercinski, A. (1972). "Inter-and Intrapopulational Racial Differentiation of Tlatilco, Cerro de Las Mesas, Teothuacan, Monte Alban and Yucatan Maya," XXXIX Congreso Intern. de Americanistas, Lima 1970, 1, 231–252.

- ^ Karl Taube, for one, says "There simply is no material evidence of any Pre-Hispanic contact between the Old World and Mesoamerica before the arrival of the Spanish in the sixteenth century.", p. 17.

- Davis, N. Voyagers to the New World, University of New Mexico Press, 1979 ISBN 0-8263-0880-5

- Williams, S. Fantastic Archaeology, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1991 ISBN 0-8122-1312-2

- Feder, K.L. Frauds, Myths, and Mysteries. Science and Pseudoscience in Archaeology 3rd ed., Trade Mayfield ISBN 0-7674-0459-9

- ^ Mexico South, Covarrubias, 1946

- ^ Ortiz de Montellano, et al. 1997, p. 217

- ^ Haslip-Viera, Gabriel: Bernard Ortiz de Montellano; Warren Barbour Source "Robbing Native American Cultures: Van Sertima's Afrocentricity and the Olmecs," Current Anthropology, 38 (3), (Tun., 1997), pp. 419–441

- ^ Diehl, Richard A. (2004). The Olmecs: America's First Civilization. London: Thames and Hudson. p. 112. ISBN 0-500-28503-9.

- ^ Milliken, William M. "Pre-Columbian Jade and Hard Stone." The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 36, no. 4 (April 1949): 53–55. Accessed 17 March 2018.

- ^ "University of East Anglia collections"[dead link], Artworld

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د The British Museum. "Olmec Stone Mask." Smarthistory.com.

- ^ "Ceremonial Ax ("Kunz Ax") | Olmec". The Metropolitan Museum of Art (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 1 فبراير 2024.

- ^ See Pool, pp. 179–242; Diehl, pp. 126–151.

- ^ Stefan Lovgren, Ancient City Found in Mexico; Shows Olmec Influence. National Geographic News, 26 January 2007

- ^ For example, Diehl, p. 170 or Pool, p. 54.

- ^ Flannery et al. (2005) hint that Olmec iconography was first developed in the Tlatilco culture.

- ^ See for example Reilly; Stevens (2007); Rose (2007). For a full discussion, see Olmec influences on Mesoamerican cultures.

- ^ Diehl, p. 111.

- ^ Pool, p. 118; Diehl, p. 112. Coe (2002), p. 69: "They wear headgear rather like American football helmets which probably served as protection in both war and in the ceremonial game played...throughout Mesoamerica."

- ^ Grove, p. 55.

- ^ Pool, p. 107.

- ^ In particular, Williams and Heizer (p. 29) calculated the weight of San Lorenzo Colossal Head 1 at 25.3 short tons, or 23 tonnes. See Scarre. pp. 271–274 for the "55 tonnes" weight.

- ^ See Williams and Heizer for more detail.

- ^ Scarre. Pool, p. 129.

- ^ Diehl, p. 119.

- ^ Wiercinski, A. (1972). "Inter-and Intrapopulational Racial Differentiation of Tlatilco, Cerro de Las Mesas, Teothuacan, Monte Alban and Yucatan Maya," XXXIX Congreso Intern. de Americanistas, Lima 1970, 1, 231–252.

- ^ Karl Taube, for one, says "There simply is no material evidence of any Pre-Hispanic contact between the Old World and Mesoamerica before the arrival of the Spanish in the sixteenth century.", p. 17.

- Davis, N. Voyagers to the New World, University of New Mexico Press, 1979 ISBN 0-8263-0880-5

- Williams, S. Fantastic Archaeology, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1991 ISBN 0-8122-1312-2

- Feder, K.L. Frauds, Myths, and Mysteries. Science and Pseudoscience in Archaeology 3rd ed., Trade Mayfield ISBN 0-7674-0459-9

- ^ Mexico South, Covarrubias, 1946

- ^ Ortiz de Montellano, et al. 1997, p. 217

- ^ Haslip-Viera, Gabriel: Bernard Ortiz de Montellano; Warren Barbour Source "Robbing Native American Cultures: Van Sertima's Afrocentricity and the Olmecs," Current Anthropology, 38 (3), (Tun., 1997), pp. 419–441

- ^ Diehl, Richard A. (2004). The Olmecs: America's First Civilization. London: Thames and Hudson. p. 112. ISBN 0-500-28503-9.

- ^ Milliken, William M. "Pre-Columbian Jade and Hard Stone." The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 36, no. 4 (April 1949): 53–55. Accessed 17 March 2018.

- ^ "University of East Anglia collections"[dead link], Artworld

- ^ "Ceremonial Ax ("Kunz Ax") | Olmec". The Metropolitan Museum of Art (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 1 فبراير 2024.

- ^ See Pool, pp. 179–242; Diehl, pp. 126–151.

- ^ Stefan Lovgren, Ancient City Found in Mexico; Shows Olmec Influence. National Geographic News, 26 January 2007

- ^ For example, Diehl, p. 170 or Pool, p. 54.

- ^ Flannery et al. (2005) hint that Olmec iconography was first developed in the Tlatilco culture.

- ^ See for example Reilly; Stevens (2007); Rose (2007). For a full discussion, see Olmec influences on Mesoamerican cultures.

- ^ See Carlson for details of the compass.

- ^ Covarrubias, p. 27.

- ^ Taube (2004), p. 122.

- ^ As one example, see Joyce et al., "Olmec Bloodletting: An Iconographic Study".

- ^ See Taube (2004), p. 122.

- ^ Pool, p. 139.

- ^ Ortiz et al., p. 249.

- ^ Pool, p. 116. Joralemon (1996), p. 218.

- ^ See Pohl et al. (2002).

- ^ "Writing May Be Oldest in Western Hemisphere". The New York Times. 15 سبتمبر 2006. Retrieved 30 مارس 2008.

- ^ "'Oldest' New World writing found". BBC. 14 سبتمبر 2006. Retrieved 30 مارس 2008.

- ^ "Oldest Writing in the New World". Science. Retrieved 30 مارس 2008.

- ^ Pohl et al. (2002).

- ^ Skidmore. These prominent proponents include Michael D. Coe, Richard Diehl, Karl Taube, and Stephen D. Houston.

- ^ Bruhns, et al.

- ^ Diehl, p. 184.

- ^ "Mesoamerican Long Count calendar & invention of the zero concept" section cited to Diehl, p. 186.

- ^ Haughton, p. 153. The earliest recovered Long Count dated is from Monument 1 in the Maya site El Baúl, Guatemala, bearing a date of 37 BCE.

- ^ Diehl, p. 106. See also J. E. Clark, p. 343, who says "much of the art of La Venta appears to have been dedicated to rulers who dressed as gods, or to the gods themselves".

- ^ Diehl, p. 106.

- ^ Diehl, pp. 103–104.

- ^ Benson (1996) p. 263.

المصادر

- Adams, Richard E.W. (1991). Prehistoric Mesoamerica (Revised ed.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2304-4. OCLC 22593466.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1876). The Native Races of the Pacific States of North America: Primitive history. 1876. Vol. Vol. 5. D. Appleton.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Benson, Elizabeth P. (1996). "110. Votive Axe". In Elizabeth P. Benson; Beatriz de la Fuente (eds.). Olmec Art of Ancient Mexico (To accompany an exhibition at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, 30 June to 20 October 1996 ed.). Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art. pp. 262–263. ISBN 0-89468-250-4. OCLC 34357584.

- Bernal, I; Coe, M; et al. (1973). The Iconography of Middle American sculpture. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. (see index)

- Bruhns, Karen O.; Nancy L. Kelker; Ma. del Carmen Rodríguez Martínez; Ponciano Ortíz Ceballos; Michael D. Coe; Richard A. Diehl; Stephen D. Houston; Karl A. Taube; Alfredo Delgado Calderón (مارس 2007). "Did the Olmec Know How to Write?". Science. Washington, D.C.: American Association for the Advancement of Science. 315 (5817): 1365–1366. doi:10.1126/science.315.5817.1365b. ISSN 0036-8075. OCLC 206052590. PMID 17347426.

- Campbell, Lyle; Terrence Kaufman (1976). "A Linguistic Look at the Olmec". American Antiquity. Menasha, WI: Society for American Archaeology. 41 (1): 80–89. doi:10.2307/279044. ISSN 0002-7316. JSTOR 279044. OCLC 1479302.

- Carlson, John B. (1975) "Lodestone Compass: Chinese or Olmec Primacy? Multidisciplinary Analysis of an Olmec Hematite Artifact from San Lorenzo, Veracruz, Mexico”, Science, New Series, 189 (4205) (5 September 1975), pp. 753–760 (753).

- Clark, John E. (2001). "Gulf Lowlands: South Region". In Susan Toby Evans; David L. Webster (eds.). Archaeology of Ancient Mexico and Central America: an Encyclopedia. New York: Garland Publishing. pp. 340–344. ISBN 0-8153-0887-6. OCLC 45313588.

- Coe, Michael D. (1967). "San Lorenzo and the Olmec Civilization". In Elizabeth P. Benson (ed.). Dumbarton Oaks Conference on the Olmec, October 28th and 29th, 1967 (PDF online reproduction). Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection; Trustees for Harvard University. pp. 41–72. OCLC 52523439.

- Coe, Michael D. (1968). America's First Civilization: Discovering the Olmec. New York: The Smithsonian Library.

- Coe, Michael D.; Rex Koontz (2002). Mexico: from the Olmecs to the Aztecs (5th edition, revised and enlarged ed.). London and New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-28346-X. OCLC 50131575.

- Covarrubias, Miguel (1977) [1946]. "Olmec Art or the Art of La Venta". In Alana Cordy-Collins; Jean Stern (eds.). Pre-Columbian Art History: Selected Readings. Translated by Robert Pirazzini (Reprint of original paper ed.). Palo Alto, CA: Peek Publications. pp. 1–34. ISBN 0-917962-41-9. OCLC 3843930.

- Covarrubias, Miguel (1957). Indian Art of Mexico and Central America (Color plates and line drawings by the author ed.). New York: Alfred A. Knopf. OCLC 171974.

- Cyphers, Ann (1996). "2. San Lorenzo Monument 4 – Colossal Head". In Elizabeth P. Benson; Beatriz de la Fuente (eds.). Olmec Art of Ancient Mexico (To accompany an exhibition at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, 30 June to 20 October 1996 ed.). Washington D.C.: National Gallery of Art. p. 156. ISBN 0-89468-250-4. OCLC 34357584.

- Cyphers, Ann (1999). "From Stone to Symbols: Olmec Art in Social Context at San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán". In David C. Grove; Rosemary A. Joyce (eds.). Social patterns in pre-classic Mesoamerica: a symposium at Dumbarton Oaks, 9 and 10 October 1993 (PDF online e-text reproduction). Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection and Trustees for Harvard University. pp. 155–181. ISBN 0-88402-252-8. OCLC 39229716.

{{cite book}}:|archive-url=requires|url=(help);|format=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Davies, Nigel (1982). The Ancient Kingdoms of Mexico. Pelican Books series. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-022232-4. OCLC 11212208.

- Diehl, Richard (2004). The Olmecs: America's First Civilization. Ancient peoples and places series. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-02119-8. OCLC 56746987.

- Filloy Nadal, Laura (2001). "Rubber and Rubber Balls in Mesoamerica". In E. Michael Whittington (ed.). The Sport of Life and Death: The Mesoamerican Ballgame (Published in conjunction with an exhibition of the same name organized by the Mint Museum of Art, Charlotte, NC. ed.). New York: Thames & Hudson. pp. 20–31. ISBN 0-500-05108-9. OCLC 49029226.

- Flannery, Kent V.; Andrew K. Balkansky; Gary M. Feinman; David C. Grove; Joyce Marcus; Elsa M. Redmond; Robert G. Reynolds; Robert J. Sharer; Charles S. Spencer; Jason Yaeger (أغسطس 2005). "Implications of new petrographic analysis for the Olmec "mother culture" model" (online reproduction). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences. 102 (32): 11219–11223. doi:10.1073/pnas.0505116102. ISSN 0027-8424. OCLC 209632728. PMC 1183595. PMID 16061797. Retrieved 27 مارس 2007.

- Grove, David C. (سبتمبر 1976). "Olmec Origins and Transpacific Diffusion: Reply to Meggers". American Anthropologist (JSTOR reproduction). New Series. Arlington, VA: American Anthropological Association and affiliated societies. 78 (3): 634–637. doi:10.1525/aa.1976.78.3.02a00120. ISSN 0002-7294. JSTOR 674425. OCLC 1479294.

{{cite journal}}:|format=requires|url=(help) - Grove, David C. (1981). "Olmec monuments: Mutilation as a Clue to Meaning". In Elizabeth P. Benson (ed.). The Olmec and their Neighbors: Essays in Memory of Matthew W. Stirling. Michael D. Coe and David C. Grove (organizers). Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection; Trustees for Harvard University. pp. 49–68. ISBN 0-88402-098-3. OCLC 7416377.

- Guimarães, A.P. (يونيو 2004). "Mexico and the early history of magnetism" (PDF online reproduction). Revista Mexicana de Física. Mexico D.F.: Sociedad Mexicana de Física. 50 (Enseñanza 1): 51–53. ISSN 0035-001X. OCLC 107737016. Retrieved 9 سبتمبر 2008.

- Haughton, Brian (2007). Hidden History. New Page Books. ISBN 978-1-56414-897-1.

- Joralemon, Peter David (1996) "[Catalogue #]53. Figure Seated on a Throne with Infant on Lap", in Olmec Art of Ancient Mexico, eds. E. P. Benson and B. de la Fuente, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., ISBN 0-89468-250-4, p. 218.

- Joyce, Rosemary A. (1991). "Olmec Bloodletting: An Iconographic Study" (PDF; reprinted online by PARI [2003]) in Sixth Palenque Round Table Conference, held 8–14 June 1986, at Palenque, Chiapas, Mexico. Virginia M. Fields (volume ed), Merle Greene Robertson (series ed.) Sixth Palenque Roundtable, 1986: 143–150, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. OCLC 21230103.

- Lawler, Andrew (2007). "Beyond the Family Feud". Archaeology. 60 (2): 20–25.

- Magni, Caterina (1999). Archéologie du Mexique: les Olmèques (in الفرنسية). Paris: Éditions Artcom’. ISBN 2-912741-24-6. OCLC 43630189.

- Magni, Caterina (2003). Les Olmèques: des origines au mythe (in الفرنسية). Paris: Éditions du Seuil. ISBN 2-02-054991-3. OCLC 52385926.

- National Science Foundation (2002) Scientists Find Earliest "New World" Writings in Mexico, 2002.

- Niederberger Betton, Christine (1987) Paléopaysages et archéologie pré-urbaine du bassin de México. Tomes I & II published by Centro Francés de Estudios Mexicanos y Centroamericanos, Mexico, D.F. (Resume)

- Ortíz C., Ponciano; Rodríguez, María del Carmen (1999) "Olmec Ritual Behavior at El Manatí: A Sacred Space" in Social Patterns in Pre-Classic Mesoamerica, eds. Grove, D. C.; Joyce, R. A., Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, D.C., pp. 225–254.

- Ortiz de Montellano, Bernard; Gabriel Haslip-Viera; Warren Barbour (Spring 1997). "They Were NOT Here before Columbus: Afrocentric Hyperdiffusionism in the 1990s". Ethnohistory. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, issued by the American Society for Ethnohistory. 44 (2): 199–234. doi:10.2307/483368. ISSN 0014-1801. JSTOR 483368. OCLC 42388116.

- Pohl, Mary; Kevin O. Pope; Christopher von Nagy (2002). "Olmec Origins of Mesoamerican Writing". Science. 298 (5600): 1984–1987. doi:10.1126/science.1078474. PMID 12471256.

- Pohl, Mary "Economic Foundations of Olmec Civilization in the Gulf Coast Lowlands of México", Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, Inc., accessed March 2007.

- Pool, Christopher A. (2007). Olmec Archaeology and Early Mesoamerica. Cambridge World Archaeology. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-78882-3. OCLC 68965709.

- Pope, Kevin; et al. (2001). "Origin and Environmental Setting of Ancient Agriculture in the Lowlands of Mesoamerica". Science. 292 (5520): 1370–1373. doi:10.1126/science.292.5520.1370. PMID 11359011.

- Reilly III, F. Kent "Art, Ritual, and Rulership in the Olmec World" in Ancient Civilizations of Mesoamerica: a Reader, Blackwell Publishing Ltd., pp. 369–395.

- Rose, Mark (2005) "Olmec People, Olmec Art", in Archaeology (online), the Archaeological Institute of America, accessed February 2007.

- Santley, Robert S.; Michael J. Berman; Rani T. Alexander (1991). "The Politicization of the Mesoamerican Ballgame and its Implications for the Interpretation of the Distribution of Ballcourts in Central Mexico". In Vernon L. Scarborough; David R. Wilcox (eds.). The Mesoamerican Ballgame. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. pp. 3–24. ISBN 0-8165-1180-2. OCLC 51873028.

- Scarre, Chris (1999) The Seventy Wonders of the Ancient World, Thames & Hudson, London, ISBN 978-0-500-05096-5.

- Serra Puche, Mari Carmen and Fernan Gonzalez de la Vara, Karina R. Durand V. (1996) "Daily Life in Olmec Times", in Olmec Art of Ancient Mexico, eds. E. P. Benson and B. de la Fuente, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., ISBN 0-89468-250-4, pp. 262–263.

- Skidmore, Joel (2006). "The Cascajal Block: The Earliest Precolumbian Writing" (PDF). Mesoweb Reports & News. Mesoweb. Retrieved 20 يونيو 2007.

- Stevenson, Mark (2007) "Olmec-influenced city found in Mexico", Associated Press, accessed 8 February 2007.

- Stirling, Matthew W. (1968). "Early History of the Olmec Problem". In Elizabeth P. Benson (ed.). Dumbarton Oaks Conference on the Olmec, October 28th and 29th, 1967 (PDF online reproduction). Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection; Trustees for Harvard University. pp. 1–8. OCLC 52523439.

{{cite book}}:|format=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - Stoltman, J.B.; et al. (2005). "Petrographic evidence shows that pottery exchange between the Olmec and their neighbors was two-way". PNAS. 102 (32): 11213–11218. doi:10.1073/pnas.0505117102. PMC 1183596. PMID 16061796.

- Taube, Karl (2004). Olmec Art at Dumbarton Oaks (PDF). Pre-Columbian Art at Dumbarton Oaks, No. 2. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection; Trustees of Harvard University. ISBN 0-88402-275-7. OCLC 56096117.

- VanDerwarker, Amber (2006) Farming, Hunting, and Fishing in the Olmec World, University of Texas Press, ISBN 0-292-70980-3.

- von Nagy, Christopher (1997). "The Geoarchaeology of Settlement in the Grijalva Delta". In Barbara L. Stark; Philip J. Arnold III (eds.). Olmec to Aztec: Settlement Patterns in the Ancient Gulf Lowlands. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. pp. 253–277. ISBN 0-8165-1689-8. OCLC 36364149.

- Wichmann, Søren (1995). The Relationship Among the Mixe–Zoquean Languages of Mexico. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. ISBN 0-87480-487-6.

- Wichmann, Søren; Dmitri Beliaev; Albert Davletshin (سبتمبر 2008). "Posibles correlaciones lingüísticas y arqueológicas involucrando a los olmecas" (PDF). Proceedings of the Mesa Redonda Olmeca: Balance y Perspectivas, Museo Nacional de Antropología, México City, March 10–12, 2005. (in الإسبانية). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 أكتوبر 2008. Retrieved 18 سبتمبر 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Wilford, John Noble (15 مارس 2005). "Mother Culture, or Only a Sister?". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 سبتمبر 2008.

- Williams, Howel; Robert F. Heizer (سبتمبر 1965). "Sources of Rocks Used in Olmec Monuments" (PDF online facsimile). Contributions of the University of California Archaeological Research Facility. Berkeley: University of California Department of Anthropology. 1 (Sources of Stones Used in Prehistoric Mesoamerican Sites): 1–44. ISSN 0068-5933. OCLC 1087514.

وصلات خارجية

- Drawings and photographs of the 17 colossal heads

- "Stone Etchings Represent Earliest New World Writing". Scientific American; Ma. del Carmen Rodríguez Martínez, Ponciano Ortíz Ceballos, Michael D. Coe, Richard A. Diehl, Stephen D. Houston, Karl A. Taube, Alfredo Delgado Calderón, Oldest Writing in the New World, Science, Vol 313, 15 September 2006, pp. 1610–1614.

- BBC audio file. Discussion of Olmec culture (15 mins) A History of the World in 100 Objects

- Smithsonian Olmec Legacy

- Articles with dead external links from November 2023

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Use dmy dates from October 2019

- Pages using multiple image with auto scaled images

- جميع الصفحات التي تحتاج تنظيف

- مقالات بالمعرفة تحتاج توضيح from January 2024

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- المقالات needing additional references from December 2018

- كل المقالات needing additional references

- Articles with unsourced statements from February 2024

- CS1 errors: extra text: volume

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- CS1 errors: format without URL

- CS1 errors: archive-url

- CS1 الفرنسية-language sources (fr)

- CS1 الإسبانية-language sources (es)

- أولمك

- تأسيسات القرن 16 ق.م. في المكسيك

- انحلالات القرن الرابع ق.م. في المكسيك

- شعوب قديمة

- ثقافات أثرية في أمريكا الشمالية

- حضارات

- الفترة التكوينية في الأمريكتين

- تاريخ گريرو

- ـاريخ تاباسكو

- تاريخ ڤيراكروز

- Hyperdiffusionism in archaeology

- ثقافات وسط أمريكا

- ثقافات ما قبل كولومبوس في المكسيك

- الشعوب الأصلية في المكسيك