التهاب الأذن الوسطى

| التهاب الأذن الوسطى | |

|---|---|

| الأسماء الأخرى | Otitis media with effusion: serous otitis media, secretory otitis media |

| |

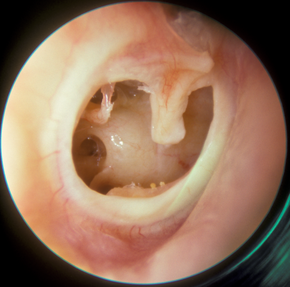

| انتفاخ الغشاء الطبلي وهي علامة نموذجية في حالة التهاب الأذن الوسطى الحاد. | |

| التخصص | طب الأنف والأذن والحنجرة |

| الأعراض | ألم الأذن، الحمى، فقدان السمع أو ضعفه[1][2] |

| الأنواع | التهاب الأذن الوسطى الحاد، التهاب الأذن الوسطى الإفرازي بإفرازات، التهاب الأذن الوسطى القيحي المزمن[3][4] |

| المسببات | Viral, bacterial[4] |

| عوامل الخطر | التعرض للدخان، العناية اليومية [4] |

| الوقاية | التطعيم، الرضاعة الطبيعية[1] |

| الدواء | پاراستامول (أستامينوفين)، آيبوپروفين، قطرة بنزوكايين[1] |

| التردد | 471 مليون (2015)[5] |

| الوفيات | 3.200 (2015)[6] |

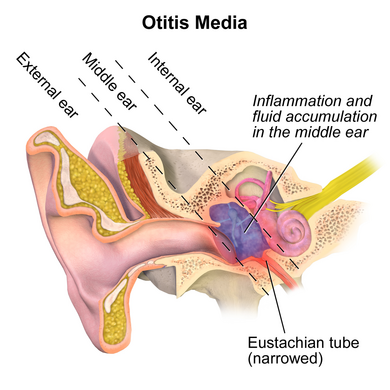

التهاب الأذن الوسطى (إنگليزية: Otitis media)، هي مجموعة من الأمراض الالتهابية التي تصيب الأذن الوسطى.[2] أحد النوعين الرئيسية هو التهاب الأذن الوسطى الحاد (AOM),[3] وهي عدوى سريعة الظهور وعادة ما تكون مصحوبة بألم في الأذن.[1] قد يؤدي ذلك عند الأطفال الصغار إلى شد الأذن وزيادة البكاء وقلة النوم.[1] قد يكون هناك أيضًا انخفاض في تناول الطعام وحمى.[1] أما النوع الرئيسي الثاني فهو التهاب الأذن الوسطى الإفرازي (OME)، الذي لا يرتبط عادة بأعراض،[1] على الرغم من وصف المريض بأنه يشعر بامتلاء الأذن؛[4] يتم تعريفه على أنه وجود سائل غير معدي في الأذن الوسطى والذي قد يستمر لأسابيع أو أشهر غالبًا بعد نوبة التهاب الأذن الوسطى الحاد.[4] التهاب الأذن الوسطى القيحي المزمن (CSOM) هو التهاب في الأذن الوسطى ينتج عنه ثقب في غشاء الطبل مع نزول إفرازات من الأذن لمدة تزيد عن ستة أسابيع.[7] وقد يكون من مضاعفات التهاب الأذن الوسطى الحاد.[4] ونادراً ما يوجد ألم.[4] قد ترتبط حالات التهاب الأذن الوسطى الثلاثة بفقدان السمع.[2][3] إذا كان الأطفال الذين يعانون من فقدان السمع بسبب التهاب الأذن الوسطى الحاد لا يتعلمون لغة الإشارة، فقد يؤثر ذلك على قدرتهم على التعلم.[8]

يرتبط سبب التهاب الأذن الوسطى الحاد بالتشريح والوظيفة المناعية في الطفولة.[4] قد تكون البكتيريا أو الڤيروسات سبباً للالتهاب.[4] تشمل عوامل الخطر التعرض للدخان، واستخدام اللهايات، والذهاب إلى الحضانات.[4] يحدث التهاب الأذن الوسطى الحاد بشكل أكثر شيوعًا بين السكان الأصليين في أستراليا وأولئك الذين لديهم الشفة المشقوقة والحنك المشقوق أو متلازمة داون.[4][9]

يحدث التهاب الأذن الوسطى الإفرازي بشكل متكرر بعد التهاب الأذن الوسطى الحاد وقد يكون مرتبطًا عدوى الجهاز التنفسي العلوي الڤيروسي، أو المهيجات مثل الدخان، أو الحساسية.[3][4] فحص طبلة الأذن هام لإجراء التشخيص الصحيح.[10] تشمل علامات التهاب الأذن الوسطى الحاد انتفاخ أو عدم تحرك الغشاء الطبلي من نفخة الهواء.[1][11] تشير الإفرازات الجديدة غير المرتبطة بالتهاب الأذن الخارجية أيضًا إلى التشخيص.[1]

هناك عدد من التدابير التي تقلل من خطر الإصابة بالتهاب الأذن الوسطى بما في ذلك لقاح المكورات الرئوية وتطعيم الأنفلونزا، الرضاعة الطبيعية، وتجنب دخان التبغ.[1] الاستخدام من مسكنات الألم في حالة التهاب الأذن الوسطى الحاد أمر هام.[1] قد يشمل ذلك الپاراستامول (الأستامينوفين)، الآيبوپروفين، قطرة بنزوكاين للأذن، أو أشباه الأفيونيات.[1] في حالة التهاب الأذن الوسطى الحاد، قد تسرع المضادات الحيوية عملية الشفاء لكنها قد تؤدي إلى آثار جانبية.[12] غالبًا ما يوصى بالمضادات الحيوية للأشخاص الذين يعانون من مرض شديد أو أقل من عامين.[11] بالنسبة لأولئك الذين يعانون من مرض أقل خطورة، قد يوصى بهم فقط لأولئك الذين لم يتحسنوا بعد يومين أو ثلاثة أيام.[11] المضاد الحيوي الأولي المفضل هو عادة أموكسيسيلين.[1] بالنسبة لأولئك الذين يعانون من الالتهابات المتكررة في أنابيب فغر الطبلة قد يقلل من تكرار المرض.[1] أما الأطفال المصابين بالتهاب الأذن الوسطى الإفرازي فقد تزيد المضادات الحيوية من القضاء على الأعراض، لكنها قد تسبب الإسهال والقيء والطفح الجلدي.[13]

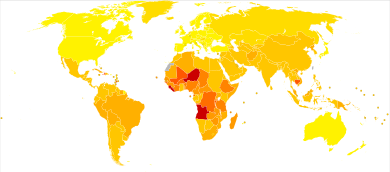

يصيب التهاب الأذن الوسطى الحاد حوالي 11% من سكان العالم سنوياً (حوالي 325-710 مليون حالة).[14][15] نصف هذه الحالات من الأطفال أقل من خمس سنوات وهو أكثر شيوعاً بين الذكور.[4][14] من بين المصابين حوالي 4.8% أو 31 مليون يصابون بالتهاب الأذن الوسطى القيحي المزمن.[14] ويقدر العدد الإجمالي للأشخاص الذين يعانون من التهاب الأذن الوسطى القيحي المزمن بنحو 65-330 مليون شخص.[16] قبل سن العاشرة يؤثر التهاب الأذن الوسطى الإفرازي على حوالي 80% من الأطفال في مرحلة عمرية ما.[4] عام 2015 أدى التهاب الأذن الوسطى إلى وفاة 3200 شخص، بانخفاض عن 4900 حالة وفاة عام 1990.[6][17]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الأعراض والعلامات

العرض الأساسي لالتهاب الأذن الوسطى الحاد هو ألم الأذن؛ تشمل الأعراض المحتملة الأخرى الحمى، انخفاض السمع خلال فترات المرض، الألم عند ملامسة الجلد فوق الأذن، إفرازات قيحية من الأذنين، التهيج، الإحساس بانسداد الأذن[18] والإسهال (عند الرضع). بما أن نوبة التهاب الأذن الوسطى عادة ما تنجم عن عدوى الجهاز التنفسي العلوي، فغالبًا ما تكون هناك أعراض مصاحبة مثل السعال وإفرازات الأنف.[1] قد يشعر المرء أيضًا بالامتلاء في الأذن.

يمكن أن يكون سبب إفرازات الأذن هو التهاب الأذن الوسطى الحاد مع ثقب طبلة الأذن، أو التهاب الأذن الوسطى القيحي المزمن، أو سيلان الأذن الأنبوبي، أو التهاب الأذن الخارجية الحاد. يمكن أن تؤدي الصدمة، مثل كسر الجمجمة القاعدي، أيضًا إلى سيلان الأذن في السائل النخاعي (تفريغ السائل الدماغي الشوكي من الأذن) بسبب التصريف الشوكي من الدماغ وغطائه (السحايا).[بحاجة لمصدر]

الأسباب

السبب الشائع لجميع أشكال التهاب الأذن الوسطى هو خلل في أنبوب استاكيوس.[19] يحدث هذا عادة بسبب التهاب الأغشية المخاطية في البلعوم الأنفي، والذي يمكن أن يحدث بسبب عدوى الجهاز التنفسي العلوي، التهاب الحلق العقدي، أو ربما بواسطة الحساسية.[20]

عن طريق الارتجاع أو شفط الإفرازات غير المرغوب فيها من البلعوم الأنفي إلى مساحة الأذن الوسطى المعقمة عادة، قد يصاب السائل بعد ذلك بالعدوى - عادةً بالبكتريا. يمكن تحديد الڤيروس الذي تسبب في عدوى الجهاز التنفسي العلوي الأولية على أنه الممراض المسبب للعدوى.[20]

التشخيص

وبما أن أعراضه النموذجية تتداخل مع حالات أخرى، مثل التهاب الأذن الوسطى الخارجي الحاد، فإن الأعراض وحدها لا تكفي للتنبؤ بوجود التهاب الأذن الوسطى الحاد؛ يجب أن يستكمل التشخيص بتصور الغشاء الطبلي.[21][22] يمكن للطبيب استخدام منظار الأذن الهوائي المزود بمصباح مطاطي متصلة لتقييم حركة الغشاء الطبلي. هناك طرق أخرى لتشخيص التهاب الأذن الوسطى باستخدام قياس الطبل، قياس الانعكاسات، أو اختبار السمع.

في الحالات الأكثر خطورة، مثل أولئك الذين يعانون من فقدان السمع المصاحب أو ارتفاع الحمى، قياس السمع، مخطط الطبل، العظم الصدغي الأشعة المقطعية والمغناطيسي يمكن استخدام التصوير بالرنين|التصوير بالرنين المغناطيسي لتقييم المضاعفات المرتبطة، مثل انصباب الخشاء، الخراج تحت السمحاق، وتكوين تدمير العظام، تجلط الدم الوريدي أو التهاب السحايا.[23]

التهاب الأذن الوسطى الحاد لدى الأطفال الذين يعانون من انتفاخ معتدل إلى شديد في غشاء الطبل أو بداية جديدة لسيل الأذن (التصريف) لا يرجع إلى التهاب الأذن الخارجية. أيضًا، يمكن إجراء التشخيص عند الأطفال الذين يعانون من انتفاخ خفيف في طبلة الأذن وبداية ألم في الأذن (أقل من 48 ساعة) أو حمامي شديد (احمرار) في طبلة الأذن.

لتأكيد التشخيص، يجب تحديد انصباب الأذن الوسطى والتهاب طبلة الأذن (يسمى التهاب الطبلة أو التهاب الطبلة)؛ ومن علاماتها الامتلاء والانتفاخ والغيوم واحمرار طبلة الأذن.[1] من المهم محاولة التمييز بين التهاب الأذن الوسطى الحاد والتهاب الأذن الوسطى الإفرازي ، حيث لا ينصح باستخدام المضادات الحيوية في التهاب الأذن الوسطى الحاد.[1] وقد اقترح أن انتفاخ الغشاء الطبلي هو أفضل علامة للتمييز بين التهاب الأذن الوسطى الحاد والتهاب الأذن الوسطى الإفرازي، حيث يشير انتفاخ الغشاء إلى التهاب الأذن الوسطى الحاد بدلاً من التهاب الأذن الوسطى الإفرازي.[24]

قد يؤدي التهاب الأذن الڤيروسي إلى ظهور بثور على الجانب الخارجي للغشاء الطبلي، وهو ما يسمى التهاب الطبلة الفقاعي (كلمة myringa كلمة لاتينية تعني "طبلة الأذن").[25]

ومع ذلك، في بعض الأحيان قد لا يكون فحص طبلة الأذن قادرًا على تأكيد التشخيص، خاصة إذا كانت القناة صغيرة. إذا كان الشمع الموجود في قناة الأذن يحجب الرؤية الواضحة لطبلة الأذن، فيجب إزالته باستخدام مكشطة صمغية غير حادة أو حلقة سلكية. كما أن بكاء طفل صغير منزعج يمكن أن يتسبب في ظهور التهاب في طبلة الأذن بسبب تمدد الأوعية الدموية الصغيرة الموجودة عليها، مما يحاكي الاحمرار المرتبط بالتهاب الأذن الوسطى.

التهاب الأذن الوسطى الحاد

البكتريا الأكثر شيوعاً المعزولة من الأذن الوسطى في حالة التهاب الأذنى الوسطى الحاد هي المكورات العقدية الرئوية، المستدمية النزلية، الموراكسيلة النزلية،[1] والمكورات العنقودية الذهبية.[26]

التهاب الأذن الوسطى الإفرازي

التهاب الأذن الوسطى الإفرازي (OME)، ويشار له بالعامية باسم "الأذن الصمغية"[27]، هو تراكم السوائل الذي قد يحدث في الأذن الوسطى والخلايا الهوائية الخشائية بسبب الضغط السلبي الناتج عن خلل في قناة استاكيوس. يمكن أن يرتبط هذا بعدوى ڤيروسية في الجهاز التنفسي العلوي أو عدوى بكتيرية مثل التهاب الأذن الوسطى.[28] يمكن أن تتسبب الإفرازات في فقدان السمع التوصيلي إذا كان يتداخل مع انتقال اهتزازات عظام الأذن الوسطى إلى مجمع العصب الدهليزي القوقعي التي يتم إنشاؤها بواسطة الموجات الصوتية.[29]

يرتبط ظهور التهاب الأذن الوسطى الإفرازي المبكر بتغذية الرضع أثناء الاستلقاء، والذهاب المبكر إلى دور الحضانة، وتدخين الوالدين، ونقص أو قصر فترة الرضاعة الطبيعية، وزيادة الوقت الذي يقضيه الرضيع في دور الحضانة، وخاصة تلك التي يتواجد فيها عدد كبير من الأطفال. عوامل الخطر هذه تزيد من حدوث ومدة التهاب الأذن الوسطى الإفرازي خلال العامين الأولين من عمر الطفل.[30]

التهاب الأذن الوسطى القيحي المزمن

التهاب الأذن الوسطى القيحي المزمن (CSOM) هو التهاب مزمن في الأذن الوسطى والتجويف الخشائي يتميز بإفرازات من الأذن الوسطى عبر غشاء الطبلة المثقوب لمدة 6 أسابيع على الأقل. يحدث التهاب الأذن الوسطى القيحي المزمن بعد عدوى الجهاز التنفسي العلوي التي أدت إلى التهاب الأذن الوسطى الحاد. يتطور هذا إلى استجابة التهابية طويلة الأمد تسبب وذمة وتقرح وانثقاب في الغشاء المخاطي (الأذن الوسطى). تحاول الأذن الوسطى حل هذا التقرح عن طريق إنتاج الأنسجة الحبيبية وتكوين الزوائد اللحمية. قد يؤدي هذا إلى زيادة الإفرازات والفشل في إيقاف الالتهاب، وتطور التهاب الأذن الوسطى القيحي المزمن، والذي غالبًا ما يرتبط أيضًا بالورم الكولسترولي. قد يكون هناك ما يكفي من القيح لتصريفه إلى خارج الأذن (سيلان أذني)، أو قد يكون القيح في حده الأدنى بدرجة كافية بحيث لا يمكن رؤيته إلا عند الفحص باستخدام منظار الأذن أو المجهر الثنائي. غالبًا ما يترافق هذا المرض بضعف السمع. يتعرض الأشخاص لخطر متزايد للإصابة بالتهاب الأذن الوسطى القيحي المزمن عندما تكون وظيفة قناة استاكيوس لديهم ضعيفة، وتاريخ من نوبات متعددة من التهاب الأذن الوسطى الحاد، ويعيشون في ظروف مزدحمة، ويحضرون مرافق الرعاية النهارية للأطفال. أولئك الذين يعانون من تشوهات القحفي الوجهي مثل الشفة والحنك المشقوق، متلازمة داون، وصغر الرأس هم أكثر عرضة للخطر.[بحاجة لمصدر]

في جميع أنحاء العالم، يتأثر سنوياً ما يقرب من 11% من السكان بالأذن الوسطى الحاد، أو 709 مليون حالة.[14][15] حوالي 4.4% من السكاني تطور لديهم إلى التهاب الأذن الوسطى القيحي المزمن.[15]

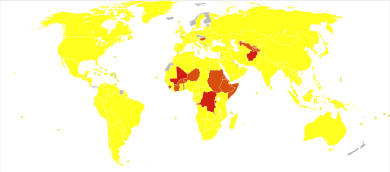

بحسب منظمة الصحة العالمية، فإن التهاب الأذن الوسطى القيحي المزمن هو السبب الرئيسي لفقدان السمع لدى الأطفال.[31] يكون البالغون الذين يعانون من نوبات متكررة من التهاب الأذن الوسطى القيحي المزمن أكثر عرضة للإصابة بفقدان السمع التوصيلي والحسي العصبي الدائم.[31] يختلف معدل حدوث التهاب الأذن الوسطى القيحي المزمن في جميع أنحاء العالم بشكل كبير حيث يكون معدل الانتشار منخفضًا نسبيًا في البلدان ذات الدخل المرتفع بينما قد يصل معدل الانتشار في البلدان منخفضة الدخل إلى ثلاثة أضعاف.[14] يتوفى سنوياً 21.000 شخص في جميع أنحاء العالم بسبب مضاعفات التهاب الأذن الوسطى القيحي المزمن.[31]

التهاب الأذن الوسطى الالتصاقي

يحدث التهاب الأذن الوسطى الصمغي عندما انكماش طبلة الأذن في منطقة الأذن الوسطى والتصاقها بعظمات الأذن الوسطى والعظام الأخرى.

الوقاية

يعد التهاب الأذن الوسطى الحاد أقل شيوعًا بكثير عند الرضع الذين يرضعون رضاعة طبيعية منه عند الرضع الذين يتغذون اصطناعياً،[32] وترتبط الحماية الأكبر بالرضاعة الطبيعية الحصرية خلال الأشهر الستة الأولى من الحياة.[1] ترتبط مدة الرضاعة الطبيعية الأطول بتأثير وقائي أطول.[32]

يقلل لقاح المكورات الرئوية (PCV) في مرحلة الطفولة المبكرة من خطر الإصابة بالتهاب الأذن الوسطى الحاد عند الرضع الأصحاء.[33] يوصى باستخدام لقاح المكورات الرئوية لجميع الأطفال، وإذا تم إعطاؤه على نطاق واسع، فسيكون للقاح فائدة كبيرة على الصحة العامة.[1] يبدو أن التطعيم ضد الأنفلونزا لدى الأطفال يقلل من معدلات الإصابة بالتهاب الأذن الوسطى الحاد بنسبة 4% واستخدام المضادات الحيوية بنسبة 11% على مدى 6 أشهر.[34] ومع ذلك، أدى اللقاح إلى زيادة الآثار الضارة مثل الحمى وسيلان الأنف.[34] إن الانخفاض الطفيف في التهاب الأذن الوسطى الحاد قد لا يبرر الآثار الجانبية والإزعاج الناتج عن التطعيم ضد الأنفلونزا كل عام لهذا الغرض وحده.[34] لا يبدو أن لقاح المكورات الرئوية يقلل من خطر الإصابة بالتهاب الأذن الوسطى عند إعطائه للرضع المعرضين لمخاطر عالية أو للأطفال الأكبر سنًا الذين عانوا سابقًا من التهاب الأذن الوسطى.[33]

من المعروف أن عوامل الخطر مثل المواسم، والاستعداد للحساسية، ووجود أشقاء أكبر سنًا هي العوامل المحددة لالتهاب الأذن الوسطى المتكرر والإفرازات المتكررة في الأذن الوسطى.[35] ارتبط تاريخ تكرار المرض، والتعرض البيئي لدخان التبغ، وذهاب الرضع لدور الرعاية النهارية، وقلة الرضاعة الطبيعية بزيادة خطر تطور وتكرار التهاب الأذن الوسطى الحاد.[36][37] ارتبط استخدام اللهاية بنوبات أكثر تكرارًا من التهاب الأذن الوسطى.[38]

المضادات الحيوية طويلة المدى، على الرغم من أنها تقلل معدلات العدوى أثناء العلاج، إلا أنها لها تأثير غير معروف على النتائج طويلة المدى مثل فقدان السمع.[39] ارتبطت طريقة الوقاية هذه بظهور بكتيريا غير مرغوب فيها بكتيريا الأذن المقاومة للمضادات الحيوية.[1]

هناك أدلة معتدلة على أن بديل السكر الزايليتول قد يقلل من معدلات الإصابة لدى الأطفال الأصحاء الذين يذهبون إلى دور الرعاية النهارية.[40]

لا تدعم الأدلة استخدام مكملات الزنك كمحاولة لتقليل معدلات التهاب الأذن باستثناء ربما عند الأشخاص الذين يعانون من سوء التغذية الشديد مثل السغل.[41]

لا تظهر المعززات الحيوية أي دليل على الوقاية من التهاب الأذن الوسطى الحاد لدى الأطفال.[42]

Management

Oral and topical pain killers are the mainstay for the treatment of pain caused by otitis media. Oral agents include ibuprofen, paracetamol (acetaminophen), and opiates. A 2023 review found evidence for the effectiveness of single or combinations of oral pain relief in acute otitis media is lacking.[43] Topical agents shown to be effective include antipyrine and benzocaine ear drops.[44] Decongestants and antihistamines, either nasal or oral, are not recommended due to the lack of benefit and concerns regarding side effects.[45] Half of cases of ear pain in children resolve without treatment in three days and 90% resolve in seven or eight days.[46] The use of steroids is not supported by the evidence for acute otitis media.[47][48]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Antibiotics

Use of antibiotics for acute otitis media has benefits and harms. As over 82% of acute episodes settle without treatment, about 20 children must be treated to prevent one case of ear pain, 33 children to prevent one perforation, and 11 children to prevent one opposite-side ear infection. For every 14 children treated with antibiotics, one child has an episode of vomiting, diarrhea or a rash.[49] Analgesics may relieve pain, if present. For people requiring surgery to treat otitis media with effusion, preventative antibiotics may not help reduce the risk of post-surgical complications.[50]

For bilateral acute otitis media in infants younger than 24 months, there is evidence that the benefits of antibiotics outweigh the harms.[12] A 2015 Cochrane review concluded that watchful waiting is the preferred approach for children over six months with non severe acute otitis media.[12]

| Summary[12] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Findings in words | Findings in numbers | Quality of evidence |

| Pain | |||

| Pain at 24 hours | Antibiotics causes little or no reduction to the chance of experiencing the outcome when compared with placebo for acute otitis media in children. Data are based on high quality evidence. | RR 0.89 (0.78 to 1.01) | High |

| Pain at 2 to 3 days | Antibiotics slightly reduces the chance of experiencing the outcome when compared with placebo for acute otitis media in children. Data are based on high quality evidence. | RR 0.70 (0.57 to 0.86) | High |

| Pain at 4 to 7 days | Antibiotics slightly reduces the chance of experiencing the outcome when compared with placebo for acute otitis media in children. Data are based on high quality evidence. | RR 0.76 (0.63 to 0.91) | High |

| Pain at 10 to 12 days | Antibiotics probably reduces the chance of experiencing the outcome when compared with placebo for acute otitis media in children. Data are based on moderate quality evidence. | RR 0.33 (0.17 to 0.66) | Moderate |

| Abnormal tympanometry | |||

| 2 to 4 weeks | Antibiotics slightly reduces the chance of experiencing the outcome when compared with placebo for acute otitis media in children. Data are based on high quality evidence. | RR 0.82 (0.74 to 0.90) | High |

| 3 months | Antibiotics causes little or no reduction to the chance of experiencing the outcome when compared with placebo for acute otitis media in children. Data are based on high quality evidence. | RR 0.97 (0.76 to 1.24) | High |

| Vomiting | |||

| Diarrhoea or rash | Antibiotics slightly increases the chance of experiencing the outcome when compared with placebo for acute otitis media in children. Data are based on high quality evidence. | RR 1.38 (1.19 to 1.59) | High |

Most children older than 6 months of age who have acute otitis media do not benefit from treatment with antibiotics. If antibiotics are used, a narrow-spectrum antibiotic like amoxicillin is generally recommended, as broad-spectrum antibiotics may be associated with more adverse events.[1][51] If there is resistance or use of amoxicillin in the last 30 days then amoxicillin-clavulanate or another penicillin derivative plus beta lactamase inhibitor is recommended.[1] Taking amoxicillin once a day may be as effective as twice[52] or three times a day. While less than 7 days of antibiotics have fewer side effects, more than seven days appear to be more effective.[53] If there is no improvement after 2–3 days of treatment a change in therapy may be considered.[1] Azithromycin appears to have less side effects than either high dose amoxicillin or amoxicillin/clavulanate.[54]

Tympanostomy tube

Tympanostomy tubes (also called "grommets") are recommended with three or more episodes of acute otitis media in 6 months or four or more in a year, with at least one episode or more attacks in the preceding 6 months.[1] There is tentative evidence that children with recurrent acute otitis media (AOM) who receive tubes have a modest improvement in the number of further AOM episodes (around one fewer episode at six months and less of an improvement at 12 months following the tubes being inserted).[55][56] Evidence does not support an effect on long-term hearing or language development.[56][57] A common complication of having a tympanostomy tube is otorrhea, which is a discharge from the ear.[58] The risk of persistent tympanic membrane perforation after children have grommets inserted may be low.[55] It is still uncertain whether or not grommets are more effective than a course of antibiotics.[55]

Oral antibiotics should not be used to treat uncomplicated acute tympanostomy tube otorrhea.[58] They are not sufficient for the bacteria that cause this condition and have side effects including increased risk of opportunistic infection.[58] In contrast, topical antibiotic eardrops are useful.[58]

Otitis media with effusion

The decision to treat is usually made after a combination of physical exam and laboratory diagnosis, with additional testing including audiometry, tympanogram, temporal bone CT and MRI.[59][60][61] Decongestants,[62] glucocorticoids,[63] and topical antibiotics are generally not effective as treatment for non-infectious, or serous, causes of mastoid effusion.[59] Moreover, it is recommended against using antihistamines and decongestants in children with OME.[62] In less severe cases or those without significant hearing impairment, the effusion can resolve spontaneously or with more conservative measures such as autoinflation.[64][65] In more severe cases, tympanostomy tubes can be inserted,[57] possibly with adjuvant adenoidectomy[59] as it shows a significant benefit as far as the resolution of middle ear effusion in children with OME is concerned.[66]

Chronic suppurative otitis media

Topical antibiotics are of uncertain benefit as of 2020.[67] Some evidence suggests that topical antibiotics may be useful either alone or with antibiotics by mouth.[67] Antiseptics are of unclear effect.[68] Topical antibiotics (quinolones) are probably better at resolving ear discharge than antiseptics.[69]

Alternative medicine

Complementary and alternative medicine is not recommended for otitis media with effusion because there is no evidence of benefit.[28] Homeopathic treatments have not been proven to be effective for acute otitis media in a study with children.[70] An osteopathic manipulation technique called the Galbreath technique[71] was evaluated in one randomized controlled clinical trial; one reviewer concluded that it was promising, but a 2010 evidence report found the evidence inconclusive.[72]

Outcomes

| no data < 10 10–14 14–18 18–22 22–26 26–30 | 30–34 34–38 38–42 42–46 46–50 > 50 |

Complications of acute otitis media consists of perforation of the ear drum, infection of the mastoid space behind the ear (mastoiditis), and more rarely intracranial complications can occur, such as bacterial meningitis, brain abscess, or dural sinus thrombosis.[73] It is estimated that each year 21,000 people die due to complications of otitis media.[14]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Membrane rupture

In severe or untreated cases, the tympanic membrane may perforate, allowing the pus in the middle-ear space to drain into the ear canal. If there is enough, this drainage may be obvious. Even though the perforation of the tympanic membrane suggests a highly painful and traumatic process, it is almost always associated with a dramatic relief of pressure and pain. In a simple case of acute otitis media in an otherwise healthy person, the body's defenses are likely to resolve the infection and the ear drum nearly always heals. An option for severe acute otitis media in which analgesics are not controlling ear pain is to perform a tympanocentesis, i.e., needle aspiration through the tympanic membrane to relieve the ear pain and to identify the causative organism(s).

Hearing loss

Children with recurrent episodes of acute otitis media and those with otitis media with effusion or chronic suppurative otitis media have higher risks of developing conductive and sensorineural hearing loss. Globally approximately 141 million people have mild hearing loss due to otitis media (2.1% of the population).[74] This is more common in males (2.3%) than females (1.8%).[74]

This hearing loss is mainly due to fluid in the middle ear or rupture of the tympanic membrane. Prolonged duration of otitis media is associated with ossicular complications and, together with persistent tympanic membrane perforation, contributes to the severity of the disease and hearing loss. When a cholesteatoma or granulation tissue is present in the middle ear, the degree of hearing loss and ossicular destruction is even greater.[75]

Periods of conductive hearing loss from otitis media may have a detrimental effect on speech development in children.[76][77][78] Some studies have linked otitis media to learning problems, attention disorders, and problems with social adaptation.[79] Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that individuals with otitis media have more depression/anxiety-related disorders compared to individuals with normal hearing.[80] Once the infections resolve and hearing thresholds return to normal, childhood otitis media may still cause minor and irreversible damage to the middle ear and cochlea.[81] More research on the importance of screening all children under 4 years old for otitis media with effusion needs to be performed.[77]

Epidemiology

Acute otitis media is very common in childhood. It is the most common condition for which medical care is provided in children under five years of age in the US.[20] Acute otitis media affects 11% of people each year (709 million cases) with half occurring in those below five years.[14] Chronic suppurative otitis media affects about 5% or 31 million of these cases with 22.6% of cases occurring annually under the age of five years.[14] Otitis media resulted in 2,400 deaths in 2013 – down from 4,900 deaths in 1990.[17]

Australian Aboriginals experience a high level of conductive hearing loss largely due to the massive incidence of middle ear disease among the young in Aboriginal communities. Aboriginal children experience middle ear disease for two and a half years on average during childhood compared with three months for non indigenous children. If untreated it can leave a permanent legacy of hearing loss.[82] The higher incidence of deafness in turn contributes to poor social, educational and emotional outcomes for the children concerned. Such children as they grow into adults are also more likely to experience employment difficulties and find themselves caught up in the criminal justice system. Research in 2012 revealed that nine out of ten Aboriginal prison inmates in the Northern Territory suffer from significant hearing loss.[83] Andrew Butcher speculates that the lack of fricatives and the unusual segmental inventories of Australian languages may be due to the very high presence of otitis media ear infections and resulting hearing loss in their populations. People with hearing loss often have trouble distinguishing different vowels and hearing fricatives and voicing contrasts. Australian Aboriginal languages thus seem to show similarities to the speech of people with hearing loss, and avoid those sounds and distinctions which are difficult for people with early childhood hearing loss to perceive. At the same time, Australian languages make full use of those distinctions, namely place of articulation distinctions, which people with otitis media-caused hearing loss can perceive more easily.[84] This hypothesis has been challenged on historical, comparative, statistical, and medical grounds.[85]

References

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س ش ص ض ط ظ ع غ ف ق ك ل م ن Lieberthal AS, Carroll AE, Chonmaitree T, Ganiats TG, Hoberman A, Jackson MA, et al. (March 2013). "The diagnosis and management of acute otitis media". Pediatrics. 131 (3): e964–999. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-3488. PMID 23439909.

- ^ أ ب ت Qureishi A, Lee Y, Belfield K, Birchall JP, Daniel M (January 2014). "Update on otitis media – prevention and treatment". Infection and Drug Resistance. 7: 15–24. doi:10.2147/IDR.S39637. PMC 3894142. PMID 24453496.

- ^ أ ب ت ث "Ear Infections". cdc.gov. September 30, 2013. Archived from the original on 19 February 2015. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س ش ص Minovi A, Dazert S (2014). "Diseases of the middle ear in childhood". GMS Current Topics in Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery. 13: Doc11. doi:10.3205/cto000114. PMC 4273172. PMID 25587371.

- ^ Vos T, Allen C, Arora M, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Brown A, et al. (GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators) (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- ^ أ ب Wang H, Naghavi M, Allen C, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Carter A, et al. (GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators) (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- ^ Emmett SD, Kokesh J, Kaylie D (November 2018). "Chronic Ear Disease". The Medical Clinics of North America. 102 (6): 1063–1079. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2018.06.008. PMID 30342609. S2CID 53045631.

- ^ Ruben, Robert J; Schwartz, Richard (February 1999). "Necessity versus sufficiency: the role of input in language acquisition". International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology (in الإنجليزية). 47 (2): 137–140. doi:10.1016/S0165-5876(98)00132-3. PMID 10206361. Archived from the original on 2018-06-14. Retrieved 2021-09-27.

- ^ "Ear disease in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children" (PDF). AIHW. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 February 2017. Retrieved 12 May 2017.

- ^ Coker TR, Chan LS, Newberry SJ, Limbos MA, Suttorp MJ, Shekelle PG, Takata GS (November 2010). "Diagnosis, microbial epidemiology, and antibiotic treatment of acute otitis media in children: a systematic review". JAMA. 304 (19): 2161–2169. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.1651. PMID 21081729.

- ^ أ ب ت "Otitis Media: Physician Information Sheet (Pediatrics)". cdc.gov. November 4, 2013. Archived from the original on 10 September 2015. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Venekamp, Roderick P.; Sanders, Sharon L.; Glasziou, Paul P.; Rovers, Maroeska M. (2023-11-15). "Antibiotics for acute otitis media in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 11 (11): CD000219. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000219.pub5. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 10646935. PMID 37965923.

- ^ Venekamp RP, Burton MJ, van Dongen TM, van der Heijden GJ, van Zon A, Schilder AG (June 2016). "Antibiotics for otitis media with effusion in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (6): CD009163. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009163.pub3. PMC 7117560. PMID 27290722.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د Monasta L, Ronfani L, Marchetti F, Montico M, Vecchi Brumatti L, Bavcar A, et al. (2012). "Burden of disease caused by otitis media: systematic review and global estimates". PLOS ONE. 7 (4): e36226. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...736226M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0036226. PMC 3340347. PMID 22558393.

- ^ أ ب ت Vos T, Barber RM, Bell B, Bertozzi-Villa A, Biryukov S, Bolliger I, et al. (Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators) (August 2015). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 386 (9995): 743–800. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(15)60692-4. PMC 4561509. PMID 26063472.

- ^ Erasmus T (2012-09-17). "Chronic suppurative otitis media". Continuing Medical Education. 30 (9): 335–336–336. ISSN 2078-5143. Archived from the original on 2020-10-20. Retrieved 2019-08-07.

- ^ أ ب GBD 2013 Mortality Causes of Death Collaborators (January 2015). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–171. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

{{cite journal}}:|author1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Meghanadh, Dr Koralla Raja (2022-01-26). "What are the symptoms for an ear infection ?". Medy Blog (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on 2022-02-17. Retrieved 2022-02-17.

- ^ Bluestone CD (2005). Eustachian tube: structure, function, role in otitis media. Hamilton, London: BC Decker. pp. 1–219. ISBN 978-1550090666.

- ^ أ ب ت Donaldson JD. "Acute Otitis Media". Medscape. Archived from the original on 28 March 2013. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ^ Laine MK, Tähtinen PA, Ruuskanen O, Huovinen P, Ruohola A (May 2010). "Symptoms or symptom-based scores cannot predict acute otitis media at otitis-prone age". Pediatrics. 125 (5): e1154–61. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-2689. PMID 20368317. S2CID 709374.

- ^ Shaikh N, Hoberman A, Kaleida PH, Ploof DL, Paradise JL (May 2010). "Videos in clinical medicine. Diagnosing otitis media – otoscopy and cerumen removal". The New England Journal of Medicine. 362 (20): e62. doi:10.1056/NEJMvcm0904397. PMID 20484393.

- ^ Patel MM, Eisenberg L, Witsell D, Schulz KA (October 2008). "Assessment of acute otitis externa and otitis media with effusion performance measures in otolaryngology practices". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 139 (4): 490–494. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2008.07.030. PMID 18922333. S2CID 24036039.

- ^ Shaikh N, Hoberman A, Rockette HE, Kurs-Lasky M (March 28, 2012). "Development of an algorithm for the diagnosis of otitis media" (PDF). Academic Pediatrics (Submitted manuscript). 12 (3): 214–218. doi:10.1016/j.acap.2012.01.007. PMID 22459064. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 26, 2020. Retrieved November 3, 2018.

- ^ Roberts DB (April 1980). "The etiology of bullous myringitis and the role of mycoplasmas in ear disease: a review". Pediatrics. 65 (4): 761–766. doi:10.1542/peds.65.4.761. PMID 7367083. S2CID 31536385.

- ^ Benninger MS (March 2008). "Acute bacterial rhinosinusitis and otitis media: changes in pathogenicity following widespread use of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 138 (3): 274–278. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2007.11.011. PMID 18312870. S2CID 207300175.

- ^ "Glue Ear". NHS Choices. Department of Health. Archived from the original on 13 November 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ^ أ ب Rosenfeld RM, Culpepper L, Yawn B, Mahoney MC (June 2004). "Otitis media with effusion clinical practice guideline". American Family Physician. 69 (12): 2776, 2778–2779. PMID 15222643.

- ^ "Otitis media with effusion: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 17 February 2017. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

- ^ Owen MJ, Baldwin CD, Swank PR, Pannu AK, Johnson DL, Howie VM (November 1993). "Relation of infant feeding practices, cigarette smoke exposure, and group child care to the onset and duration of otitis media with effusion in the first two years of life". The Journal of Pediatrics. 123 (5): 702–711. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(05)80843-1. PMID 8229477.

- ^ أ ب ت Acuin J, WHO Dept. of Child and Adolescent Health and Development, WHO Programme for the Prevention of Blindness and Deafness (2004). Chronic suppurative otitis media : burden of illness and management options. Geneve: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/42941. ISBN 978-9241591584.

- ^ أ ب Lawrence R (2016). Breastfeeding : a guide for the medical profession, 8th edition. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier. pp. 216–217. ISBN 978-0-323-35776-0.

- ^ أ ب Fortanier, Alexandre C.; Venekamp, Roderick P.; Boonacker, Chantal Wb; Hak, Eelko; Schilder, Anne Gm; Sanders, Elisabeth Am; Damoiseaux, Roger Amj (28 May 2019). "Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines for preventing acute otitis media in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 5 (5): CD001480. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001480.pub5. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6537667. PMID 31135969.

- ^ أ ب ت Norhayati MN, Ho JJ, Azman MY (October 2017). "Influenza vaccines for preventing acute otitis media in infants and children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017 (10): CD010089. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010089.pub3. PMC 6485791. PMID 29039160.

- ^ Rovers MM, Schilder AG, Zielhuis GA, Rosenfeld RM (February 2004). "Otitis media". Lancet. 363 (9407): 465–473. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15495-0. PMID 14962529. S2CID 30439271.

- ^ Pukander J, Luotonen J, Timonen M, Karma P (1985). "Risk factors affecting the occurrence of acute otitis media among 2–3-year-old urban children". Acta Oto-Laryngologica. 100 (3–4): 260–265. doi:10.3109/00016488509104788. PMID 4061076.

- ^ Etzel RA (February 1987). "Smoke and ear effusions". Pediatrics. 79 (2): 309–311. doi:10.1542/peds.79.2.309a. PMID 3808812. S2CID 1350590.

- ^ Rovers MM, Numans ME, Langenbach E, Grobbee DE, Verheij TJ, Schilder AG (August 2008). "Is pacifier use a risk factor for acute otitis media? A dynamic cohort study". Family Practice. 25 (4): 233–236. doi:10.1093/fampra/cmn030. PMID 18562333.

- ^ Leach AJ, Morris PS (October 2006). Leach AJ (ed.). "Antibiotics for the prevention of acute and chronic suppurative otitis media in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD004401. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004401.pub2. PMID 17054203.

- ^ Azarpazhooh A, Lawrence HP, Shah PS (August 2016). "Xylitol for preventing acute otitis media in children up to 12 years of age". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (8): CD007095. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007095.pub3. PMC 8485974. PMID 27486835.

- ^ Gulani A, Sachdev HS (June 2014). "Zinc supplements for preventing otitis media". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (6): CD006639. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006639.pub4. PMC 9392835. PMID 24974096.

- ^ Scott, Anna M; Clark, Justin; Julien, Blair; Islam, Farhana; Roos, Kristian; Grimwood, Keith; Little, Paul; Del Mar, Chris B (18 June 2019). "Probiotics for preventing acute otitis media in children". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (6): CD012941. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012941.pub2. PMC 6580359. PMID 31210358.

- ^ de Sévaux, JLH; Damoiseaux, RA; van de Pol, AC; Lutje, V; Hay, AD; Little, P; Schilder, AG; Venekamp, RP (18 August 2023). "Paracetamol (acetaminophen) or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, alone or combined, for pain relief in acute otitis media in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2023 (8): CD011534. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011534.pub3. PMC 10436353. PMID 37594020.

- ^ Sattout A (February 2008). "Best evidence topic reports. Bet 1. The role of topical analgesia in acute otitis media". Emergency Medicine Journal. 25 (2): 103–4. doi:10.1136/emj.2007.056648. PMID 18212148. S2CID 34753900.

- ^ Coleman C, Moore M (July 2008). Coleman C (ed.). "Decongestants and antihistamines for acute otitis media in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD001727. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001727.pub4. PMID 18646076. قالب:Retracted

- ^ Thompson M, Vodicka TA, Blair PS, Buckley DI, Heneghan C, Hay AD (December 2013). "Duration of symptoms of respiratory tract infections in children: systematic review". BMJ. 347: f7027. doi:10.1136/bmj.f7027. PMC 3898587. PMID 24335668.

- ^ Principi N, Bianchini S, Baggi E, Esposito S (February 2013). "No evidence for the effectiveness of systemic corticosteroids in acute pharyngitis, community-acquired pneumonia and acute otitis media". European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases. 32 (2): 151–60. doi:10.1007/s10096-012-1747-y. PMC 7087613. PMID 22993127.

- ^ Ranakusuma RW, Pitoyo Y, Safitri ED, Thorning S, Beller EM, Sastroasmoro S, Del Mar CB (March 2018). "Systemic corticosteroids for acute otitis media in children" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (3): CD012289. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012289.pub2. PMC 6492450. PMID 29543327. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-10-30. Retrieved 2019-12-16.

- ^ Venekamp, Roderick P.; Sanders, Sharon L.; Glasziou, Paul P.; Rovers, Maroeska M. (2023-11-15). "Antibiotics for acute otitis media in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 11 (11): CD000219. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000219.pub5. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 10646935. PMID 37965923.

- ^ Verschuur HP, de Wever WW, van Benthem PP (2004). "Antibiotic prophylaxis in clean and clean-contaminated ear surgery". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010 (3): CD003996. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003996.pub2. PMC 9037065. PMID 15266512.

- ^ Coon ER, Quinonez RA, Morgan DJ, Dhruva SS, Ho T, Money N, Schroeder AR (April 2019). "2018 Update on Pediatric Medical Overuse: A Review". JAMA Pediatrics. 173 (4): 379–384. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.5550. PMID 30776069. S2CID 73495617.

- ^ Thanaviratananich S, Laopaiboon M, Vatanasapt P (December 2013). "Once or twice daily versus three times daily amoxicillin with or without clavulanate for the treatment of acute otitis media". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12 (12): CD004975. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004975.pub3. PMID 24338106.

- ^ Kozyrskyj A, Klassen TP, Moffatt M, Harvey K (September 2010). "Short-course antibiotics for acute otitis media". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010 (9): CD001095. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001095.pub2. PMC 7052812. PMID 20824827.

- ^ Hum SW, Shaikh KJ, Musa SS, Shaikh N (December 2019). "Adverse Events of Antibiotics Used to Treat Acute Otitis Media in Children: A Systematic Meta-Analysis". The Journal of Pediatrics. 215: 139–143.e7. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2019.08.043. PMID 31561959. S2CID 203580952.

- ^ أ ب ت Venekamp RP, Mick P, Schilder AG, Nunez DA (May 2018). "Grommets (ventilation tubes) for recurrent acute otitis media in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 5 (6): CD012017. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012017.pub2. PMC 6494623. PMID 29741289.

- ^ أ ب Steele DW, Adam GP, Di M, Halladay CH, Balk EM, Trikalinos TA (June 2017). "Effectiveness of Tympanostomy Tubes for Otitis Media: A Meta-analysis". Pediatrics. 139 (6): e20170125. doi:10.1542/peds.2017-0125. PMID 28562283.

- ^ أ ب Browning GG, Rovers MM, Williamson I, Lous J, Burton MJ (October 2010). "Grommets (ventilation tubes) for hearing loss associated with otitis media with effusion in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (10): CD001801. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001801.pub3. PMID 20927726. S2CID 43568574.

- ^ أ ب ت ث American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question, American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, http://www.choosingwisely.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Choosing-Wisely-Recommendations.pdf, retrieved on August 1, 2013, which cites

- Rosenfeld RM, Schwartz SR, Pynnonen MA, Tunkel DE, Hussey HM, Fichera JS, et al. (July 2013). "Clinical practice guideline: Tympanostomy tubes in children". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 149 (1 Suppl): S1–35. doi:10.1177/0194599813487302. PMID 23818543.

- ^ أ ب ت Rosenfeld RM, Shin JJ, Schwartz SR, Coggins R, Gagnon L, Hackell JM, et al. (February 2016). "Clinical Practice Guideline: Otitis Media with Effusion (Update)". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 154 (1 Suppl): S1–S41. doi:10.1177/0194599815623467. PMID 26832942. S2CID 33459167. Archived from the original on 2019-03-06. Retrieved 2019-03-05.

- ^ Wallace IF, Berkman ND, Lohr KN, Harrison MF, Kimple AJ, Steiner MJ (February 2014). "Surgical treatments for otitis media with effusion: a systematic review". Pediatrics. 133 (2): 296–311. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-3228. PMID 24394689. S2CID 2355197.

- ^ Rosenfeld RM, Schwartz SR, Pynnonen MA, Tunkel DE, Hussey HM, Fichera JS, et al. (July 2013). "Clinical practice guideline: Tympanostomy tubes in children". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 149 (1 Suppl): S1-35. doi:10.1177/0194599813487302. PMID 23818543.

- ^ أ ب Griffin G, Flynn CA (September 2011). "Antihistamines and/or decongestants for otitis media with effusion (OME) in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011 (9): CD003423. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003423.pub3. PMC 7170417. PMID 21901683.

- ^ Simpson SA, Lewis R, van der Voort J, Butler CC (May 2011). "Oral or topical nasal steroids for hearing loss associated with otitis media with effusion in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011 (5): CD001935. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001935.pub3. PMC 9829244. PMID 21563132.

- ^ Blanshard JD, Maw AR, Bawden R (June 1993). "Conservative treatment of otitis media with effusion by autoinflation of the middle ear". Clinical Otolaryngology and Allied Sciences. 18 (3): 188–92. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2273.1993.tb00827.x. PMID 8365006.

- ^ Perera R, Glasziou PP, Heneghan CJ, McLellan J, Williamson I (May 2013). "Autoinflation for hearing loss associated with otitis media with effusion". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (5): CD006285. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006285.pub2. PMID 23728660.

- ^ van den Aardweg MT, Schilder AG, Herkert E, Boonacker CW, Rovers MM (January 2010). "Adenoidectomy for otitis media in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD007810. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007810.pub2. PMID 20091650.

- ^ أ ب Brennan-Jones CG, Head K, Chong LY, Burton MJ, Schilder AG, Bhutta MF, et al. (Cochrane ENT Group) (January 2020). "Topical antibiotics for chronic suppurative otitis media". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1): CD013051. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013051.pub2. PMC 6956124. PMID 31896168.

- ^ Head K, Chong LY, Bhutta MF, Morris PS, Vijayasekaran S, Burton MJ, et al. (January 2020). Cochrane ENT Group (ed.). "Topical antiseptics for chronic suppurative otitis media". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1): CD013055. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013055.pub2. PMC 6956662. PMID 31902140.

- ^ Head K, Chong LY, Bhutta MF, Morris PS, Vijayasekaran S, Burton MJ, et al. (Cochrane ENT Group) (January 2020). "Antibiotics versus topical antiseptics for chronic suppurative otitis media". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (11): CD013056. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013056.pub2. PMC 6956626. PMID 31902139.

- ^ Jacobs J, Springer DA, Crothers D (February 2001). "Homeopathic treatment of acute otitis media in children: a preliminary randomized placebo-controlled trial". The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 20 (2): 177–183. doi:10.1097/00006454-200102000-00012. PMID 11224838.

- ^ Pratt-Harrington D (October 2000). "Galbreath technique: a manipulative treatment for otitis media revisited". The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 100 (10): 635–9. PMID 11105452. S2CID 245177279. Archived from the original on 2023-05-24. Retrieved 2023-05-24.

- ^ Bronfort G, Haas M, Evans R, Leininger B, Triano J (February 2010). "Effectiveness of manual therapies: the UK evidence report". Chiropractic & Osteopathy. 18 (1): 3. doi:10.1186/1746-1340-18-3. PMC 2841070. PMID 20184717.

- ^ Jung TT, Alper CM, Hellstrom SO, Hunter LL, Casselbrant ML, Groth A, et al. (April 2013). "Panel 8: Complications and sequelae". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 148 (4 Suppl): E122–143. doi:10.1177/0194599812467425. PMID 23536529. S2CID 206466859.

- ^ أ ب Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Michaud C, Ezzati M, et al. (December 2012). "Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2163–96. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2. PMC 6350784. PMID 23245607.

- ^ da Costa SS, Rosito LP, Dornelles C (February 2009). "Sensorineural hearing loss in patients with chronic otitis media". European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology. 266 (2): 221–4. doi:10.1007/s00405-008-0739-0. hdl:10183/125807. PMID 18629531. S2CID 2932807.

- ^ Roberts K (June 1997). "A preliminary account of the effect of otitis media on 15-month-olds' categorization and some implications for early language learning". Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 40 (3): 508–18. doi:10.1044/jslhr.4003.508. PMID 9210110.

- ^ أ ب Simpson SA, Thomas CL, van der Linden MK, Macmillan H, van der Wouden JC, Butler C (January 2007). "Identification of children in the first four years of life for early treatment for otitis media with effusion". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010 (1): CD004163. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004163.pub2. PMC 8765114. PMID 17253499.

- ^ Macfadyen, C. A.; Acuin, J. M.; Gamble, C. (2005-10-19). "Topical antibiotics without steroids for chronically discharging ears with underlying eardrum perforations". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2005 (4): CD004618. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004618.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6669264. PMID 16235370.

- ^ Bidadi S, Nejadkazem M, Naderpour M (November 2008). "The relationship between chronic otitis media-induced hearing loss and the acquisition of social skills". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 139 (5): 665–70. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2008.08.004. PMID 18984261. S2CID 37667672.

- ^ Gouma P, Mallis A, Daniilidis V, Gouveris H, Armenakis N, Naxakis S (January 2011). "Behavioral trends in young children with conductive hearing loss: a case-control study". European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology. 268 (1): 63–6. doi:10.1007/s00405-010-1346-4. PMID 20665042. S2CID 24611204.

- ^ Yilmaz S, Karasalihoglu AR, Tas A, Yagiz R, Tas M (February 2006). "Otoacoustic emissions in young adults with a history of otitis media". The Journal of Laryngology and Otology. 120 (2): 103–7. doi:10.1017/S0022215105004871. PMID 16359151. S2CID 23668097.

- ^ "Damien Howard & Dianne Hampton, "Ear disease and Aboriginal families," Aboriginal and Islander Health Worker Journal, July-August 2006, 30 (4) p.9". Archived from the original on 2023-10-16. Retrieved 2023-09-06.

- ^ "Farah Farouque, "Hearing loss hits NT indigenous inmates," The Age, 5 March 2012". 4 March 2012. Archived from the original on 6 September 2023. Retrieved 6 September 2023.

- ^ Butcher 2018.

- ^ Fergus, Anelisa (2019). Lend Me Your Ears: Otitis Media and Aboriginal Australian languages (PDF) (BA). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-10-10. Retrieved 2023-09-06.

- (2018) "The special nature of Australian phonologies: Why auditory constraints on human language sound systems are not universal" in 176th Meeting of Acoustical Society of America. 35, Acoustical Society of America. doi:10.1121/2.0001004.

External links

- Neff MJ (June 2004). "AAP, AAFP, AAO-HNS release guideline on diagnosis and management of otitis media with effusion". American Family Physician. 69 (12): 2929–2931. PMID 15222658.

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|

- CS1 errors: generic name

- CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list

- الصفحات بخصائص غير محلولة

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- Articles with unsourced statements from June 2020

- Pages using div col with small parameter

- Otitis

- Diseases of middle ear and mastoid

- Pediatrics

- Audiology

- Wikipedia medicine articles ready to translate

- Wikipedia emergency medicine articles ready to translate

- Otorhinolaryngology

- Otology