الوقت القياسي

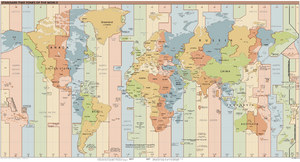

الوقت القياسي Standard time هو نظام زمني عالمي، يقسم العالم إلى 24 نطاقاً توقيتياً، يبلغ عرض كل نطاق منها 15 درجة طولية. يبلغ فرق الوقت بين النطاقات المتجاورة ساعة واحدة بالضبط. وفي داخل كل نطاق تُظْهر جميع الساعات التوقيت نفسه، باستثناء الاختلافات المحلية.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

التاريخ

قبل تطبيق الوقت القياسي، كانت كل مدينة، تستخدم التوقيت المحلي لخط الزوال الخاص بها. وبانتشار استخدام خطوط السكك الحديدية، نجم بعض المشاكل عن الاختلافات في التوقيت؛ إذ إن قطارات السكك الحديدية، التي تتقابل في المدينة نفسها، كانت، في بعض الأحيان، تتحرك في أوقات مختلفة.

أمريكا الشمالية

حتى 1883، كل سكة حديد في الولايات المتحدة اختارت وقتها القياسي. The Pennsylvania Railroad used the "Allegheny Time" system, an astronomical timekeeping service which had been developed by Samuel Pierpont Langley at the University of Pittsburgh’s Allegheny Observatory (then known as the Western University of Pennsylvania, located in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania). Instituted in 1869, the Allegheny Observatory's service is believed to have been the first regular and systematic system of time distribution to railroads and cities as well as the origin of the modern standard time system.[1] By 1870 the Allegheny Time service extended over 2,500 miles with 300 telegraph offices receiving time signals.[2]

However, almost all railroads out of New York ran on New York time, and railroads west from Chicago mostly used Chicago time, but between Chicago and Pittsburgh/Buffalo the norm was Columbus time, even on railroads such as the PFtW&C and LS&MS, which did not run through Columbus. The Santa Fe Railroad used Jefferson City (Missouri) time all the way to its west end at Deming, New Mexico, as did the east–west lines across Texas; Central Pacific and Southern Pacific Railroads used San Francisco time all the way to El Paso. The Northern Pacific Railroad had seven time zones between St. Paul and the 1883 west end of the railroad at Wallula Jct; the Union Pacific Railway was at the other extreme, with only two time zones between Omaha and Ogden.[3]

In 1870, Charles F. Dowd proposed four time zones based on the meridian through Washington, DC for North American railroads.[4] In 1872 he revised his proposal to base it on the Greenwich meridian. Sandford Fleming, a Scottish-born Canadian engineer, proposed worldwide Standard Time at a meeting of the Royal Canadian Institute on February 8, 1879.[5] Cleveland Abbe advocated standard time to better coordinate international weather observations and resultant weather forecasts, which had been coordinated using local solar time. In 1879 he recommended four time zones across the contiguous United States, based upon Greenwich Mean Time.[6] The General Time Convention (renamed the American Railway Association in 1891), an organization of US railroads charged with coordinating schedules and operating standards, became increasingly concerned that if the US government adopted a standard time scheme it would be disadvantageous to its member railroads. William F. Allen, the Convention secretary, argued that North American railroads should adopt a five-zone standard, similar to the one in use today, to avoid government action. On October 11, 1883, the heads of the major railroads met in Chicago at the Grand Pacific Hotel[7] and agreed to adopt Allen's proposed system.

The members agreed that on Sunday, November 18, 1883, all United States and Canadian railroads would readjust their clocks and watches to reflect the new five-zone system on a telegraph signal from the Allegheny Observatory in Pittsburgh at exactly noon on the 90th meridian.[8][9][10] Although most railroads adopted the new system as scheduled, some did so early on October 7 and others late on December 2. The Intercolonial Railway serving the Canadian maritime provinces of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia just east of Maine decided not to adopt Intercolonial Time based on the 60th meridian west of Greenwich, instead adopting Eastern Time, so only four time zones were actually adopted by U.S./Canadian railroads in 1883.[9] Major American observatories, including the Allegheny Observatory, the United States Naval Observatory, the Harvard College Observatory, and the Yale University Observatory, agreed to provide telegraphic time signals at noon Eastern Time.[9][10]

وفي عام 1884، طبقت السكك الحديدية، في الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية وكندا، نظامًا للوقت القياسي. وفي العام نفسه، عُقد مؤتمر دولي في واشنطن دي. سي.، لبحث نظام عالمي للوقت القياسي، واختيرت دائرة خط الطول، التي تمر بالبلدة الإنجليزية جرينتش (هي الآن، أحد الأقسام الإدارية في لندن)، لتكون دائرة الخط الأول.

وفي الوقت الحاضر، تستخدم جميع الدول، تقريباً، الوقت القياسي. ويتبع قليل من البلدان الصغيرة، وبعض المناطق الأخرى فقط ـ توقيتاً، يختلف بكسر من الساعة عن الوقت القياسي.

نطاقات التوقيت

يعتمد الوقت المحلي، أو الشمسي، لأي موقع محدد، على خط الطول الخاص به. ويوجد فرق، مقداره أربع دقائق لكل درجة من خط الطول، أو ساعة واحدة لكل 15 درجة. وبمقتضى نظام الوقت القياسي، فإن الوقت المعتمد لكل منطقة، هو توقيت خط الزوال، أو خط الطول. وخطوط الزوال المركزية هي: 15 درجة، 30 درجة، 45 درجة .. وهكذا، شرق خط الزوال الأول أو غربه، وهو خط طول جرينتش. ومن الناحية النظرية، فإن حدود النطاق، يجب أن تمتد 7.5 درجات على كلٍّ من جانبَي خط الزوال المركزي. أما من الناحية العملية، فإن الحدود غير منتظمة؛ وذلك لتجنّب التغيرات غير المريحة في الوقت. مثلاً في الدول ذات المساحات الشاسعة، مثل أستراليا أو الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية، تعيِّن، غالبًا، حدود النطاقات تعيينًا، يجعل الولاية، كلية، في نطاق زمني واحد.

وفي بعض الدول، تقدَّم الساعة، في جزء من السنة؛ لتوفير ساعات أطول من النهار؛ ففي المملكة المتحدة، مثلاً، تُقدَّم الساعة ساعة واحدة، خلال الفترة، التي تمثّل وقت الصيف الإنجليزي.

انظر أيضاً

الهامش

- ^ Walcott, Charles Doolittle (1912). Biographical Memoir of Samuel Pierpont Langley, 1834–1906. National Academy of Sciences. p. 248. Retrieved September 10, 2013.

- ^ Butowsky, Harry (1989). "Allegheny Observatory". Astronomy and Astrophysics. National Park Service. Retrieved September 10, 2013.

- ^ October 1883 Travelers Official Guide

- ^ Charles F. Dowd, A.M., Ph.D.; a narrative of his services ..., ed. Charles North Dowd, (New York: Knickerbocker Press, 1930)

- ^ "Sir Sandford Fleming 1827–1915" (PDF). Ontario Heritage Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 July 2014. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ^ Edmund P. Willis & William H. Hooke (11 May 2009). "Cleveland Abbe and American Meteorology: 1871–1901". American Meteorological Society. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ^ "Standard time system plaque". Flickr. 15 December 2005.

- ^ Parkinson, J. Robert (February 15, 2004). "When it comes to time zones in the United States, it's all business". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Archived from the original on July 25, 2006. Retrieved September 10, 2013.

- ^ أ ب ت W. F. Allen, "History of the movement by which the adoption of standard time was consummated", Proceedings of the American Metrological [ك] Society 4 (1884) 25–50, Appendix 50–89. Hathi Trust Digital Library.

- ^ أ ب Michael O'Malley, Keeping Watch: A History of American Time (NY 1990) chapter three