فن الرسم الصيني

| Chinese painting | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

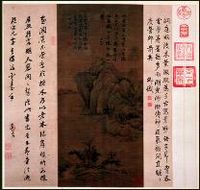

A hanging scroll Chinese painting by Ma Lin in 13th Century. Ink and color on silk, 226.6x110.3 cm. | |||||||

| |||||||

| الصينية التقليدية | 中國畫 | ||||||

| الصينية المبسطة | 中国画 | ||||||

| |||||||

فن الرسم الصيني (الصينية المبسطة: 中国画؛ الصينية التقليدية: 中國畫؛ پنين: Zhōngguó huà�) هو أحد أقدم التقاليد الفنية المستمرة في العالم. Painting in the traditional style is known today in Chinese as guó huà (الصينية المبسطة: 国画؛ الصينية التقليدية: 國畫�), meaning "national painting" or "native painting", as opposed to Western styles of art which became popular in China in the 20th century. It is also called danqing (صينية: 丹青؛ پنين: dān qīng�). Traditional painting involves essentially the same techniques as calligraphy and is done with a brush dipped in black ink or coloured pigments; oils are not used. As with calligraphy, the most popular materials on which paintings are made are paper and silk. The finished work can be mounted on scrolls, such as hanging scrolls or handscrolls. Traditional painting can also be done on album sheets, walls, lacquerware, folding screens, and other media.

The two main techniques in Chinese painting are:

- Gongbi (工筆), meaning "meticulous", uses highly detailed brushstrokes that delimit details very precisely. It is often highly colored and usually depicts figural or narrative subjects. It is often practiced by artists working for the royal court or in independent workshops.

- Ink and wash painting, in Chinese shuǐ-mò (水墨, "water and ink") also loosely termed watercolor or brush painting, and also known as "literati painting", as it was one of the "four arts" of the Chinese Scholar-official class.[1] In theory this was an art practiced by gentlemen, a distinction that begins to be made in writings on art from the Song dynasty, though in fact the careers of leading exponents could benefit considerably.[2] This style is also referred to as "xieyi" (寫意) or freehand style.

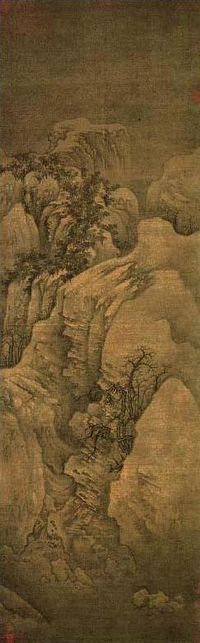

Landscape painting was regarded as the highest form of Chinese painting, and generally still is.[3] The time from the Five Dynasties period to the Northern Song period (907–1127) is known as the "Great age of Chinese landscape". In the north, artists such as Jing Hao, Li Cheng, Fan Kuan, and Guo Xi painted pictures of towering mountains, using strong black lines, ink wash, and sharp, dotted brushstrokes to suggest rough stone. In the south, Dong Yuan, Juran, and other artists painted the rolling hills and rivers of their native countryside in peaceful scenes done with softer, rubbed brushwork. These two kinds of scenes and techniques became the classical styles of Chinese landscape painting.

يُطلق لفظ التصوير الصيني على فنون كل من الصين واليابان وكوريا. يرى كثير من المؤرخين أن فترة أسرة سونج (960-1279م) قمة ماوصل إليه التصوير الصيني، فقد تأثّرت بها كل الفترات اللاحقة. وهذا لايعني أن التصوير الصيني قد بدأ في هذه الفترة، فهناك أعمال فنية رائعة تعود إلى ماقبل 2000 سنة.

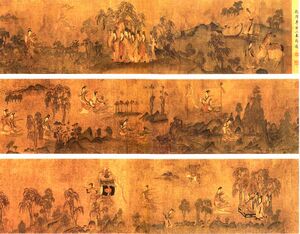

والفن الصيني لايقلد الطبيعة وله أسلوب محدّد ومبسّط اتبعه كل الفنانين التقليديين في تلك البلاد حتى بداية القرن العشرين. وبما أن كل المعتقدات الدينية الصينية ركّزت على حبِّ الطبيعة فإن الفنانين قد اهتموا بتصوير المناظر الطبيعية، والطيور والزهور والجبال والبحار. وقد استخدم كثير منهم اللون الأسود فقط بدرجاته المختلفة. وقد اهتم المصورون الصينيون بلمسات الفرشاة ووضعها أكثر من اهتمامهم بالموضوع نفسه، وصوروا لوحاتهم على الحرير، وعلى المراوح الورقيّة والجدران.واللوحة الصينية التقليدية تكون في شكل ملفوفة طويلة، وعند المشاهدة يبدأ الناظر إليها بفتح الجزء الأول ثم يبدأ في لفِّ الجزء الذي شاهده بيده اليمنى ويفتح الجزء الذي لم يشاهده بيده اليسرى حتى يُكمل مشاهدة كل اللوحة.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

التفاصيل والدراسة

Chinese painting and calligraphy distinguish themselves from other cultures' arts by emphasis on motion and change with dynamic life.[4] The practice is traditionally first learned by rote, in which the master shows the "right way" to draw items. The apprentice must copy these items strictly and continuously until the movements become instinctive. In contemporary times, debate emerged on the limits of this copyist tradition within modern art scenes where innovation is the rule. Changing lifestyles, tools, and colors are also influencing new waves of masters.[4][5]

الفترات المبكرة

The earliest paintings were not representational but ornamental; they consisted of patterns or designs rather than pictures. Early pottery was painted with spirals, zigzags, dots, or animals. It was only during the Eastern Zhou (770–256 BC) that artists began to represent the world around them. In imperial times (beginning with the Eastern Jin dynasty), painting and calligraphy in China were among the most highly appreciated arts in the court and they were often practiced by amateurs—aristocrats and scholar-officials—who had the leisure time necessary to perfect the technique and sensibility necessary for great brushwork. Calligraphy and painting were thought to be the purest forms of art. The implements were the brush pen made of animal hair, and black inks made from pine soot and animal glue. In ancient times, writing, as well as painting, was done on silk. However, after the invention of paper in the 1st century AD, silk was gradually replaced by the new and cheaper material. Original writings by famous calligraphers have been greatly valued throughout China's history and are mounted on scrolls and hung on walls in the same way that paintings are.

Artists from the Han (206 BC – 220 AD) to the Tang (618–906) dynasties mainly painted the human figure. Much of what we know of early Chinese figure painting comes from burial sites, where paintings were preserved on silk banners, lacquered objects, and tomb walls. Many early tomb paintings were meant to protect the dead or help their souls to get to paradise. Others illustrated the teachings of the Chinese philosopher Confucius or showed scenes of daily life.

During the Six Dynasties period (220–589), people began to appreciate painting for its own beauty and to write about art. From this time we begin to learn about individual artists, such as Gu Kaizhi. Even when these artists illustrated Confucian moral themes – such as the proper behavior of a wife to her husband or of children to their parents – they tried to make the figures graceful.

Six principles

The "Six principles of Chinese painting" were established by Xie He, a writer, art historian and critic in 5th century China, in "Six points to consider when judging a painting" (繪畫六法, Pinyin: Huìhuà Liùfǎ), taken from the preface to his book "The Record of the Classification of Old Painters" (古畫品錄; Pinyin: Gǔhuà Pǐnlù). Keep in mind that this was written circa 550 CE and refers to "old" and "ancient" practices. The six elements that define a painting are:

- "Spirit Resonance", or vitality, which refers to the flow of energy that encompasses theme, work, and artist. Xie He said that without Spirit Resonance, there was no need to look further.

- "Bone Method", or the way of using the brush, refers not only to texture and brush stroke, but to the close link between handwriting and personality. In his day, the art of calligraphy was inseparable from painting.

- "Correspondence to the Object", or the depicting of form, which would include shape and line.

- "Suitability to Type", or the application of color, including layers, value, and tone.

- "Division and Planning", or placing and arrangement, corresponding to composition, space, and depth.

- "Transmission by Copying", or the copying of models, not from life only but also from the works of antiquity.

أسرتي سوي وتانگ (581–960)

أسرتي سونگ ويوان (960–1368)

أواخر الإمبراطورية الصينية (1368–1895)

الرسم الحديث

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

منذ 1978

انظر أيضا

| Paintings from China

]].- Bird-and-flower painting

- فن صيني

- Chinese Piling paintings

- تاريخ الفن الشرقي

- تاريخ الفن الصيني

- تاريخ الرسم

- Ink and wash painting

- Lin Tinggui

- قائمة الرسامين الصينيين

- Ming Dynasty painting

- Qiu Ying

- Shan Shui painting

- مو كي

المصادر

- ^ Sickman, 222

- ^ Rawson, 114–119; Sickman, Chapter 15

- ^ Rawson, 112

- ^ أ ب (Stanley-Baker 2010a)

- ^ (Stanley-Baker 2010b)

- ^ Shao Xiaoyi. "Yue Fei's facelift sparks debate". China Daily. Retrieved 2007-08-09.

قراءات إضافية

- Siren, O., A History of Later Chinese Painting - 2 vols. (Medici Society, London, 1937).

وصلات خارجية

- Chinese Painting and Galleries at China Online Museum

- Famous Chinese Painters and their Galleries at China Online Museum

- Chinese Paintings and Arts Gallery with Classifieds and Auction features

- Gallery featuring ancient Chinese paintings and calligraphy from Eastern Chin dynasty (AD 317) to the 20th Century

- A Gallery of Classical Chinese Paintings

- Chinese Painting Articles

- Chinese Sumi-e by Artist Sheng Kuan Chung

- Chinese painting Description of the techniques. Learn Chinese traditional painting.

- Gallery of Chinese Painting

- Famous Chinese Painting Reproductions, famous Chinese gongbi paintings reproduced by Chinese artist Cao Xiaohui.

- Traditional Chinese Paintings

- Chinese paintings with cats throughout the centuries at the National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan

- Gallery of China Traditional Chinese Art

- Harv and Sfn no-target errors

- Short description matches Wikidata

- Articles containing صينية-language text

- مقالات تحتوي نصوصاً باللغة الصينية المبسطة

- مقالات تحتوي نصوصاً باللغة الصينية التقليدية

- مقالات تحتوي نصوصاً باللغة الصينية

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- فن صيني

- رسم صيني

- الفنون في الصين