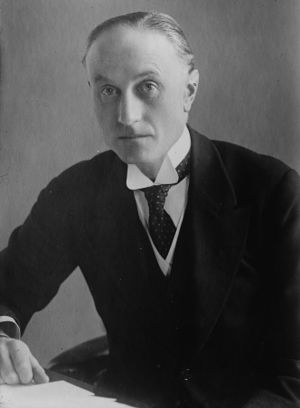

صاموِل هور، ڤايكونت تمپلويد الأول

Samuel John Gurney Hoare, 1st Viscount Templewood, GCSI, GBE, CMG, PC, JP, , , , , , , , , , , , , , , (24 February 1880 – 7 May 1959), more commonly known as Sir Samuel Hoare, was a senior British Conservative politician who served in various Cabinet posts in the Conservative and National governments of the 1920s and 1930s.[1]

He was Secretary of State for Air during most of the 1920s. As Secretary of State for India in the early 1930s, he authored the Government of India Act 1935, which granted provincial-level self government to India. He is most famous for serving as Foreign Secretary in 1935, when he authored the Hoare–Laval Pact with French Prime Minister Pierre Laval. This partially recognised the Italian conquest of Abyssinia (modern Ethiopia) and Hoare was forced to resign by the ensuing public outcry. In 1936 he returned to the Cabinet as First Lord of the Admiralty, then served as Home Secretary from 1937 to 1939 and was again briefly Secretary of State for Air in 1940. He was seen as a leading "appeaser" and his removal from office (along with that of Sir John Simon and the removal of Neville Chamberlain as Prime Minister) was a condition of Labour's agreement to serve in a coalition government in May 1940.[1]

He was British ambassador to Spain from 1940 to 1944.[1]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

السياسة بين الحربين

Secretary of State for India

Hoare was one of the Conservative negotiators in talks with Ramsay MacDonald in August 1931 over the formation of the National Government. On 26 August 1931 Hoare was appointed Secretary of State for India.[2]

At the Second Round Table Conference, Hoare enjoyed good relations with Gandhi. He committed Britain to eventual self-government for India, although this was not enough for Gandhi, who wanted full independence. Lord Lothian's report on the extension of the Indian franchise was considered.[2] A White paper containing the government's legislative proposals for India’s constitution was drawn up (March 1933).[3] A Select Committee of Both Houses met for over a year and half, beginning in April 1933, to consider the government’s plans.[2] In January 1934 Hoare was appointed Knight Grand Commander of the Star of India (GCSI) in the New Year Honours.[4][5]

Ill feeling between Hoare and Churchill, who opposed Indian self-government, reached its peak in April 1934. The Government proposed that the Indian Government retain the power to impose tariffs on British textiles. The Manchester Chamber of Commerce, representing the Lancashire cotton trade, initially opposed this, wanting Lancashire goods to be exported freely to India. Churchill accused Hoare of having, with the aid of the Earl of Derby, breached Parliamentary Privilege by improperly influencing the Manchester Chamber of Commerce to drop its opposition. Hoare was completely exonerated by the Committee on Privileges. Churchill gave a powerful speech in the Commons Chamber attacking the committee’s findings. On 13 June 1934 Leo Amery spoke, arguing that Churchill’s true aim was to bring down the government under the cover of the doctrine “fiat justicia ruat caelum” (may justice be done, though the heavens fall). Churchill, who was neither a lawyer nor a classicist, growled “translate it!” Amery replied that it meant “If I can trip up Sam, the Government’s bust”. The ensuing laughter made Churchill look ridiculous.[5]

The Select Committee of Both Houses finished its deliberations in November 1934. The result was one of the most complicated pieces of legislation in British parliamentary history, a bill which spent the first half of 1935 passing through Parliament before becoming the Government of India Act 1935.[2] The Bill contained 473 clauses and 16 schedules, and the debates took up 4,000 pages of Hansard. Hoare had to answer 15,000 questions and make 600 speeches, and he completely dominated the committee stage of the bill, just as he had the Round Table Conferences, through his mastery of detail and skill at dealing tactfully with deputations.[6] Alec Douglas-Home, later to be Prime Minister, commented in his autobiography; “The most noteworthy performance of that Parliament was without question the piloting of the India Independence Bill through the House of Commons by the Secretary of State, Sir Samuel Hoare, ably assisted by Mr. R. A. Butler (later Lord Butler)."[7] Butler, who as Under-Secretary helped to steer the bill through the Commons, later wrote of Hoare that he saw life as “a chapter in a great Napoleonic biography”, adding “I was amazed by his ambition; I admired his imagination; I shared his ideals; I stood in awe of his intellectual capacity. But I was never touched by his humanity. He was the coldest fish with whom I ever had to deal.”[3]

Hoare was widely praised for his conduct as India Secretary, but was close to exhaustion after the difficult passage of the bill, which was opposed by Churchill and by many rank-and-file Conservatives. The Act became law in August 1935, after Hoare had moved on to his next job.[5]

Although provincial governments were elected in 1937, the India Act was never fully implemented because of the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939.[5]

Foreign Secretary

In June 1935 Baldwin became Prime Minister for the third time. He offered Hoare a choice of the job of Viceroy of India or Foreign Secretary. Hoare, who was ambitious to become Prime Minister, chose the latter as it enabled him to remain active in domestic politics. The job would make him notorious.[5]

Hoare took office against a backdrop of what Adams describes as “much idle talk” of “mutual security”. In March 1935 MacDonald’s White Paper had committed Britain to limited rearmament.[5]

Italy, which also controlled Libya at the time, straddled Britain’s sea route across the Mediterranean to Egypt, the Suez Canal and India. Mussolini’s bombast was not taken very seriously in Britain.[8] In April 1935 MacDonald and Foreign Secretary Sir John Simon had signed the Stresa Front of 14 April 1935, an alliance with France and Italy (which had been an Allied power in World War One and was suspicious of German designs on Austria). The Front did not last.[8][5] It came to nothing as Britain, without consulting her partners, signed the Anglo-German Naval Agreement; this dismayed the French, who soon signed an equally unilateral treaty with the USSR.[5]

By mid-1935 Mussolini was clearly preparing to attack Abyssinia. On 12 September 1935 Hoare gave what Adams calls “the greatest speech of his career” to the League General Assembly at Geneva. He declared that Britain stood “for steady and collective resistance to all acts of unprovoked aggression”. His speech was widely praised in the world press, but did not deter the full-scale Italian invasion of Abyssinia on 3 October. Limited sanctions were imposed on Italy, but not oil sanctions.[5] A General Election took place on 14 November 1935.[5] At the election over 90% of the candidates supported the League of Nations, and there was much call for sanctions against Italy even though this was not necessarily in Britain’s interests.[8]

With the election out of the way, the government, with the agreement of the League Council, authorised Hoare to find a solution. Hoare sent Sir Maurice Peterson, head of the Foreign Office Abyssinia Department, to Paris to negotiate a compromise offer to Mussolini. Agreement was reached by the end of November: Italy was to gain territory in the north, with the rump of Abyssinia to be an Italian client state, her army under Italian control. Abyssinia had not been consulted.[5] By December 1935 Hoare was still in poor health and suffering from fainting spells since his stressful period passing the Government of India Act. Suffering from a serious infection, he stopped off in Paris on his way to a skating holiday in Switzerland. The ensuing Hoare–Laval Pact with French Prime Minister Pierre Laval was unanimously approved by the Cabinet on 9–10 December.[9]

The Pact was leaked first to the French then to the British press, causing public outcry, not least because of memories of Hoare's recent Geneva speech. Hoare, who had been injured in a skating accident, returned to Britain on 16 December.[9] Cabinet met on the morning of 18 December. Lord Halifax, who was due to make a statement in the Lords that afternoon, insisted that Hoare must resign to save the government’s position, causing J. H. Thomas, William Ormsby-Gore and Walter Elliott also to come out for his resignation. Privately Halifax was puzzled by the moral outrage as the Hoare-Laval proposals were little different from those put forward by the League Committee of Five.[8]

Hoare resigned on 18 December.[9] His successor was Anthony Eden. When Eden had his first audience with King George V, the King is said to have remarked humorously, "No more coals to Newcastle, no more Hoares to Paris."

In his memoirs Hoare admitted that his negotiations in Paris with Laval had caught him at a disadvantage. He noted that in the absence of the Hoare–Laval Pact the Italians seized all of Ethiopia, and drew closer to Germany leading eventually to the destabilisation of Austria and the indefensibility of Czechoslovakia.

First Lord of the Admiralty

It was widely recognised that Hoare had been a scapegoat for Cabinet policy. His return to Baldwin's Cabinet as First Lord of the Admiralty in June 1936 was widely praised in the press.[9] This was too quickly, thought Lord Halifax. Eden later wrote in his memoirs that Halifax “criticised Baldwin sharply for yielding to Hoare’s importunity”.[8] Hoare vigorously endorsed Britain's naval rearmament, including ordering the first three King George V-class battleships, and worked to reverse the subordination of the British naval aviation to the Royal Air Force.

References

- ^ أ ب ت "TEMPLEWOOD, 1st Viscount". Who Was Who. Oxford University Press. December 2007. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ^ أ ب ت ث خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةMatthew 2004, p365 - ^ أ ب Butler 1971, p. 57.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةburkes - ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز Matthew 2004, p366

- ^ Butler 1971, pp. 55-6.

- ^ The Way the Wind Blows, An Autobiography by Lord Home, (1976), ISBN 0 00 211997-8, pp. 56–58.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Roberts 1991, pp78-9

- ^ أ ب ت ث Matthew 2004, p367

Bibliography

- Adams, R. J. Q. (1993). British Politics and Foreign Policy in the Age of Appeasement, 1935-1939. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-2101-1.

- Braddick, H. B. (1962) "The Hoare-Laval Plan: A Study in International Politics" Review of Politics 24#3 (1962), pp. 342–364. in JSTOR

- Burdick, Charles B. (1968). Germany's Military strategy and Spain In World War II. Syracuse Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-608-18105-9.

- Coutts, Matthew Dean. (2011). "The Political Career of Sir Samuel Hoare during the National Government 1931-40" (PhD dissertation University of Leicester, 2011). online bibliography on pp 271–92.

- Cross, J. A. (1997). Sir Samuel Hoare A Political Biography. London. ISBN 0-224-01350-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Jago, Michael Rab Butler: The Best Prime Minister We Never Had?, Biteback Publishing 2015 ISBN 978-1849549202

- Jenkins, Roy (1999). The Chancellors. London: Papermac. ISBN 0333730585. (essay on Simon, pp365–92)

- Leitz, Cristian (1995). Economic relations between Nazi Germany and Franco's Spain, 1936 - 1945. Oxford: Oxford Historical Monographs, Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-820645-3.

- Matthew, Colin (2004). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 27. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198614111.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) (pp. 364–8), essay on Hoare written by R. J. Q. Adams. - Roberts, Andrew, The Holy Fox The Life of Lord Halifax. London, 1991.

- Robertson, J. C. (1975) "The Hoare-Laval Plan", Journal of Contemporary History 10#3 (1975), pp. 433–464. in JSTOR

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Primary sources

- Butler, Rab (1971). The Art of the Possible. London: Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 978-0241020074.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hayes, Carlton J. H. (1945). Wartime mission in Spain, 1942-1945. London: Macmillan. ISBN 9781121497245.

- Hoare, Sir Samuel (1925). A Flying Visit to the Middle East. Cambridge University Press.

- Hoare, Viscount Templewood, Sir Samuel (1977) [1946]. Sedmay (ed.). Ambassador on Special Mission. Madrid: Collins.

- Hoare, Viscount Templewood, Sir Samuel (1947). Complacent Dictator. A.A. Knopf. ASIN B0007F2ZVU.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lord Home (1976). The Way the Wind Blows: An Autobiography. ISBN 0 00 211997-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by Samuel Hoare

- Newspaper clippings about صاموِل هور، ڤايكونت تمپلويد الأول in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- Pages using infobox officeholder with unknown parameters

- CS1 maint: location missing publisher

- 1880 births

- 1959 deaths

- خريجو جامعة أكسفورد

- أشخاص تعلموا في مدرسة هارو

- وزراء الدولة البريطانيون للشئون الخارجية

- Secretaries of State for the Home Department

- وزراء دولة بريطانيون

- Norfolk Yeomanry officers

- Royal Army Service Corps officers

- Honorary air commodores

- First Lords of the Admiralty

- اللوردات حملة ختم الخاصة الملكية

- Conservative Party (UK) MPs for English constituencies

- UK MPs 1910

- UK MPs 1910–18

- UK MPs 1918–22

- UK MPs 1922–23

- UK MPs 1923–24

- UK MPs 1924–29

- UK MPs 1929–31

- UK MPs 1931–35

- UK MPs 1935–45

- أعضاء مجلس الخاصة الملكية بالمملكة المتحدة

- أنگليكان إنگليز

- Viscounts in the Peerage of the United Kingdom

- Companions of the Order of St Michael and St George

- Knights Grand Commander of the Order of the Star of India

- صليب الفرسان الأعظم من مرتبة الامبراطورية البريطانية

- Knights Grand Cross of the Order of Orange-Nassau

- Grand Crosses of the Order of the White Lion

- Commanders Grand Cross of the Order of the Polar Star

- Grand Crosses of the Order of the Dannebrog

- حائزو مرتبة القديسة آنا

- Recipients of the Order of Saint Stanislaus

- Recipients of the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus

- Diplomatic peers

- Chancellors of the University of Reading

- Ambassadors of the United Kingdom to Spain

- أعضاء مجلس مقاطعة لندن

- Municipal Reform Party politicians

- Secretaries of State for Air (UK)