هارتفورد، كنتيكت

هارتفورد

Hartford | |

|---|---|

|

From top to bottom, left to right: Downtown seen from the Connecticut River, Hartford Seminary, Old State House, University of Connecticut School of Law, Connecticut State Capitol, and the Cheney Building | |

الكنية:

| |

| الشعار: Post Nubila Phoebus (Latin) "After the clouds, the sun"[1] | |

| خطأ لوا في وحدة:Mapframe على السطر 384: attempt to perform arithmetic on local 'lat_d' (a nil value). | |

| الإحداثيات: 41°45′45″N 72°40′27″W / 41.76250°N 72.67417°WCoordinates: 41°45′45″N 72°40′27″W / 41.76250°N 72.67417°W | |

| البلد | United States |

| State | Connecticut |

| County | Hartford |

| Region | Capitol Region |

| MSA | Greater Hartford |

| Settled | October 15, 1635 |

| Named | February 21, 1637[2] |

| Incorporated (city) | May 29, 1784[3] |

| Consolidated | April 1, 1896[4] |

| السمِيْ | Hertford, Hertfordshire |

| الحكومة | |

| • النوع | Mayor-council |

| • Mayor | Luke Bronin (D) |

| المساحة | |

| • State capital | 18٫05 ميل² (46٫76 كم²) |

| • البر | 17٫38 ميل² (45٫01 كم²) |

| • الماء | 0٫68 ميل² (1٫75 كم²) |

| • الحضر | 535٫93 ميل² (1٬388٫0 كم²) |

| المنسوب | 30 ft (9 m) |

| التعداد (2020) | |

| • State capital | 121٬054 |

| • الكثافة | 6٬965٫1/sq mi (2٬689٫5/km2) |

| • Urban | 977٬158 (US: 47th) |

| • الكثافة الحضرية | 1٬823٫3/sq mi (704٫0/km2) |

| • العمرانية | 1٬214٬295 (US: 48th) |

| • CSA | 1٬489٬361 (US: 41st) |

| صفة المواطن | Hartfordite |

| منطقة التوقيت | UTC−05:00 (EST) |

| • الصيف (التوقيت الصيفي) | UTC−04:00 (EDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 061xx |

| مفتاح الهاتف | 860/959 |

| FIPS code | 09-37000 |

| GNIS feature ID | 2378277[7] |

| Primary airport | Bradley International Airport |

| Secondary airport | Hartford–Brainard Airport |

| Interstates | |

| U.S. Highways | |

| State routes | |

| Commuter rail | |

| Rapid transit | |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | www |

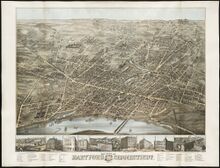

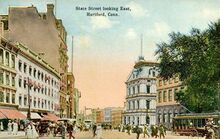

هارتفوردHartford, Connecticut مدينة أمريكية وعاصمة ولاية كونتيكت بالولايات المتحدة الأمريكية وثانية المدن الكبرى فيها.عدد سكانها 139,739 نسمة، و عدد سكان المنطقة الحضرية 1,157,585 نسمة. ويتركز السكان في مدينة بريدجپورت، كنتيكت. وتوجد نحو 40 شركة تأمين مراكزها الرئيسية في مدينة هارتفورد لذلك تعرف بمدينة التأمين، وتعتبر مركزًا مهمًا للتصنيع. وتقع هارتفورد على الضفة الغربية من نهر كونتيكت في الجزء المركزي الشمالي من الولاية. والصناعات الرئيسية هي صناعة الطائرات والآلات والأدوات الكهربائية والكيميائيات والآلات الدقيقة والمعدات. Census estimates since the 2010 United States census have indicated that Hartford is the fourth-largest city in Connecticut with a 2020 population of 121,054, behind the coastal cities of Bridgeport, New Haven, and Stamford.[8]

Hartford was founded in 1635 and is among the oldest cities in the United States. It is home to the country's oldest public art museum (Wadsworth Atheneum), the oldest publicly funded park (Bushnell Park), the oldest continuously published newspaper (the Hartford Courant), and the second-oldest secondary school (Hartford Public High School). It was home to the oldest "asylum for the deaf and dumb" the (American School for the Deaf), founded by Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet in 1817. It is also home to the Mark Twain House, where the author wrote his most famous works and raised his family, among other historically significant sites. Mark Twain wrote in 1868, "Of all the beautiful towns it has been my fortune to see this is the chief."[بحاجة لمصدر]

Hartford has been the sole capital of Connecticut since 1875.[9] Before then, New Haven and Hartford alternated as dual capitals, as part of the agreement by which the Colony of New Haven was absorbed into the Colony of Connecticut in 1664.[10]

Hartford was the richest city in the United States for several decades following the American Civil War.[11] Since 2015, it has been one of the poorest cities in the country, with three out of ten families living below the poverty threshold. In sharp contrast, the Greater Hartford metropolitan statistical area was ranked 32nd of 318 metropolitan areas in total economic production and 8th out of 280 metropolitan statistical areas in per capita income in 2015.[12]

Nicknamed the "Insurance Capital of the World", the city holds high sufficiency as a global city, as home to the headquarters of many insurance companies, the region's major industry.[13] Other prominent industries include the services, education and healthcare industries. Hartford coordinates certain Hartford-Springfield regional development matters through the Knowledge Corridor Economic Partnership.[14]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

التاريخ

Various tribes lived in or around Hartford, all Algonquian peoples. These included the Podunks, mostly east of the Connecticut River; the Poquonocks north and west of Hartford; the Massacoes in the Simsbury area; the Tunxis tribe in West Hartford and Farmington; the Wangunks to the south; and the Saukiog in Hartford itself.[15]

Colonial Hartford

The first Europeans known to have explored the area were the Dutch under Adriaen Block, who sailed up the Connecticut in 1614. Dutch fur traders from New Amsterdam returned in 1623 with a mission to establish a trading post and fortify the area for the Dutch West India Company. The original site was located on the south bank of the Park River in the present-day Sheldon/Charter Oak neighborhood. This fort was called Fort Hoop or the "House of Hope." In 1633, Jacob Van Curler formally bought the land around Fort Hoop from the Pequot chief for a small sum. It was home to perhaps a couple of families and a few dozen soldiers. The fort was abandoned by 1654, but the area is known today as Dutch Point; the name of the Dutch fort "House of Hope" is reflected in the name of Huyshope Avenue.[16][17] A significant reason for establishment of the Dutch trading post was to better control the flow of wampum, the de facto currency of New Netherlands and portions of New England, to and from valuable Native American fur traders.[18]

The Dutch outpost and the tiny contingent of Dutch soldiers who were stationed there did little to check the English migration, and the Dutch soon realized that they were vastly outnumbered. The House of Hope remained an outpost, but it was steadily swallowed up by waves of English settlers. In 1650, Peter Stuyvesant met with English representatives to negotiate a permanent boundary between the Dutch and English colonies; the line that they agreed on was more than 50 miles (80 km) west of the original settlement.

The English began to arrive in 1636, settling upstream from Fort Hoop near the present-day Downtown and Sheldon/Charter Oak neighborhoods.[19] Puritan pastors Thomas Hooker and Samuel Stone, along with Governor John Haynes, led 100 settlers with 130 head of cattle in a trek from Newtown in the Massachusetts Bay Colony (now Cambridge) and started their settlement just north of the Dutch fort.[20] The settlement was originally called Newtown, but it was changed to Hartford in 1637 in honor of Stone's hometown of Hertford, England. Hooker also created the nearby town of Windsor in 1633.[21] The etymology of Hartford is the ford where harts cross, or "deer crossing."

As the Puritan minister in Hartford, Thomas Hooker wielded a great deal of power; in 1638, he delivered a sermon that inspired the writing of the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut, which provided a framework for Connecticut's separation for Massachusetts Bay Colony and the formation of a civil government. The Fundamental Orders of Connecticut were the legal basis for Connecticut Colony until the 1662 royal charter granted to Connecticut by Charles II.[22]

The original settlement area contained the site of the Charter Oak, an old white oak tree in which colonists hid Connecticut's Royal Charter of 1662 to protect it from confiscation by an English governor-general. The state adopted the oak tree as the emblem on the Connecticut state quarter. The Charter Oak Monument is located at the corner of Charter Oak Place, a historic street, and Charter Oak Avenue.[23]

19th century

Political turmoil

On December 15, 1814, delegates from the five New England states (Maine was still part of Massachusetts at that time) gathered at the Hartford Convention to discuss New England's possible secession from the United States.[24] During the early 19th century, the Hartford area was a center of abolitionist activity, and the most famous abolitionist family was the Beechers. The Reverend Lyman Beecher was an important Congregational minister known for his anti-slavery sermons.[25][26] His daughter Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote Uncle Tom's Cabin; her brother Henry Ward Beecher was a noted clergyman who vehemently opposed slavery and supported the temperance movement and women's suffrage.[27][28] The Stowes' sister Isabella Beecher Hooker was a leading member of the women's rights movement.[29]

In 1860, Hartford was the site of the first "Wide Awakes", abolitionist supporters of Abraham Lincoln. These supporters organized torch-light parades that were both political and social events, often including fireworks and music, in celebration of Lincoln's visit to the city. This type of event caught on and eventually became a staple of mid-to-late 19th-century campaigning.[30]

Hartford was a major manufacturing city from the 19th century until the mid-20th century. During the Industrial Revolution into the mid-20th century, the Connecticut River Valley cities produced many major precision manufacturing innovations. Among these was Hartford's pioneer bicycle and automobile maker Pope.[31] Many factories have been closed or relocated, or have reduced operations, as in nearly all former Northern manufacturing cities.

Rise of a major manufacturing center

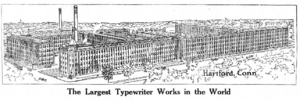

Around 1850, Hartford native Samuel Colt perfected the precision manufacturing process that enabled the mass production of thousands of his revolvers with interchangeable parts. A variety of industries adopted and adapted these techniques over the next several decades, and Hartford became the center of production for a wide array of products, including: Colt, Richard Gatling, and John Browning firearms; Weed sewing machines; Columbia bicycles; Pope automobiles; and leading typewriter manufacturers Royal Typewriter Company and Underwood Typewriter Company which together made Hartford the “Typewriter Capitol of the World” during the first half of the 20th century.[32]

The Pratt & Whitney Company was founded in Hartford in 1860 by Francis A. Pratt and Amos Whitney. They built a substantial factory in which the company manufactured a wide range of machine tools, including tools for the makers of sewing machines, and gun-making machinery for use by the Union Army during the American Civil War. In 1925, the company expanded into aircraft engine design at its Hartford factory.

Just three years after Colt's first factory opened, the Sharps Rifle Manufacturing Company set up shop in 1852 at a nearby site along the now-buried Park River, located in the present-day neighborhood of Frog Hollow. Their factory heralded the beginning of the area's transformation from marshy farmland into a major industrial zone. The road leading from town to the factory was called Rifle Lane; the name was later changed to College Street and then Capitol Avenue.[33] A century earlier, mills had located along the Park River because of the water power, but by the 1850s water power was approaching obsolescence. Sharps located there specifically to take advantage of the railroad line that had been constructed alongside the river in 1838.

The Sharps Rifle Company failed in 1870, and the Weed Sewing Machine Company took over its factory. The invention of a new type of sewing machine led to a new application of mass production after the principles of interchangeability were applied to clocks and guns. The Weed Company played a major role in making Hartford one of three machine tool centers in New England and even outranked the Colt Armory in nearby Coltsville in size.[33] Weed eventually became the birthplace of both the bicycle and automobile industries in Hartford.

Industrialist Albert Pope was inspired by a British-made, high-wheeled bicycle (called a velocipede) that he saw at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition, and he bought patent rights for bicycle production in the United States. He wanted to contract out his first order, however, so he approached George Fairfield of Weed Sewing Machine Company, who produced Pope's first run of bicycles in 1878.[34] Bicycles proved to be a huge commercial success, and production expanded in the Weed factory, with Weed making every part but the tires. Demand for bicycles overshadowed the failing sewing machine market by 1890, so Pope bought the Weed factory, took over as its president, and renamed it the Pope Manufacturing Company. The bicycle boom was short-lived, peaking near the turn of the century when more and more consumers craved individual automobile travel, and Pope's company suffered financially from over-production amidst falling demand.

In an effort to save his business, Pope opened a motor carriage department and turned out electric carriages, beginning with the "Mark III" in 1897. His venture might have made Hartford the capital of the automobile industry were it not for the ascendancy of Henry Ford and a series of pitfalls and patent struggles that outlived Pope himself.[35]

In 1876, Hartford Machine Screw was granted a charter "for the purpose of manufacturing screws, hardware and machinery of every variety." The basis for its incorporation was the invention of the first single-spindle automatic screw machine. For its next four years, the new firm occupied one of Weed's buildings, milling thousands of screws daily on over 50 machines. Its president was George Fairfield, who ran Weed, and its superintendent was Christopher Spencer, one of Connecticut's most versatile inventors. Soon Hartford Machine Screw outgrew its quarters and built a new factory adjacent to Weed, where it remained until 1948.[36]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

20th century

On the week of April 12, 1909, the Connecticut River reached a record flood stage of 24.5 feet (7.5 meters) above the low-water mark, flooding the city of Hartford and doing great damage.[37] On July 6, 1944, Hartford was the scene of one of the worst fire disasters in the history of the United States. Claiming the lives of 168 persons, mostly children and their mothers, and injuring several hundred more. It occurred at a matinee performance of the Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey Circus on Barbour Street in the city's north end and became known as the Hartford Circus Fire.[38]

After World War II, many residents of Puerto Rico moved to Hartford.[39] Starting in the late 1950s, the suburbs ringing Hartford began to grow and flourish and the capital city began a long decline. Insurance giant Connecticut General (now CIGNA) moved to a new, modern campus in the suburb of Bloomfield. Constitution Plaza had been hailed as a model of urban renewal, but it gradually became a concrete office park.[40] Once-flourishing department stores shut down, such as Brown Thomson, Sage-Allen, and G. Fox & Co., as suburban malls grew in popularity, such as Westfarms and Buckland Hills.[41]

In 1997, the city lost its professional hockey franchise, with the Hartford Whalers moving to Raleigh, North Carolina—despite an increase in season ticket sales and an offer from the state for a new arena.[42] In 2005, a developer from Newton, Massachusetts tried unsuccessfully to bring an NHL team back to Hartford and house them in a new, publicly funded stadium.[43]

Hartford experienced problems as the population shrank 11 percent during the 1990s.[44] Only Flint, Michigan; Gary, Indiana; St. Louis, Missouri; and Baltimore, Maryland experienced larger population losses during the decade. However, the population has increased since the 2000 Census.[45]

In 1987, Carrie Saxon Perry was elected mayor of Hartford, becoming the first female African-American mayor of a major American city.[46] Riverfront Plaza was opened in 1999, connecting the riverfront and the downtown area for the first time since the 1960s.[47]

21st century

A significant number of cultural events and performances take place every year at Mortensen Plaza (Riverfront Recapture Organization) by the banks of the Connecticut River.[48] These events are held outdoors and include live music, festivals, dance, arts and crafts.[48] Hartford also has a vibrant theater scene with major Broadway productions at the Bushnell Theater as well as performances at the Hartford Stage and TheaterWorks (City Arts).[49][50]

In July 2017, Hartford considered filing Chapter 9 bankruptcy. After years of shrinking population base and high pension obligations,[51] a $65 Million Dollar budget gap was projected for the year of 2018.[52] The city had cut budget of public services and gotten union concessions however these measures did not balance the budget.[51] A state bailout later that year kept the city from filing for bankruptcy.[53][54][55]

Downtown Hartford is busy during the day with commuters, but tends to be quiet in the evenings and weekends. However, more residential and retail development in recent years has begun changing the pattern.[56]

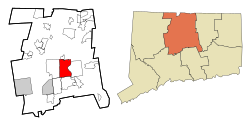

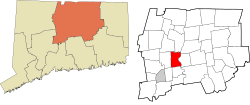

الجغرافيا

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 18.0 square miles (47 km2), of which 17.3 square miles (45 km2) is land and 0.7 square miles (1.8 km2) (3.67%) is water.[57][58]

The city of Hartford is bordered by the towns of West Hartford, Newington, Wethersfield, East Hartford, Bloomfield, South Windsor, Glastonbury, and Windsor. The Connecticut River forms the boundary between Hartford and East Hartford, and is located on the east side of the city.[59]

The Park River originally divided Hartford into northern and southern sections and was a major part of Bushnell Park, but the river was nearly completely enclosed and buried by flood control projects in the 1940s.[60] The former course of the river can still be seen in some of the roadways that were built in the river's place, such as Jewell Street and the Conlin-Whitehead Highway.[61]

المناخ

| بيانات مناخ Hartford | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| الشهر | يناير | فبراير | مارس | أبريل | مايو | يونيو | يوليو | أغسطس | سبتمبر | اكتوبر | نوفمبر | ديسمبر | العام |

| العظمى القياسية °ف (°س) | 65 (18.3) |

73 (22.8) |

89 (31.7) |

96 (35.6) |

99 (37.2) |

100 (37.8) |

102 (38.9) |

102 (38.9) |

99 (37.2) |

91 (32.8) |

81 (27.2) |

76 (24.4) |

102 (38٫9) |

| العظمى المتوسطة °ف (°س) | 34.1 (1.17) |

37.7 (3.17) |

47.7 (8.72) |

59.9 (15.5) |

71.7 (22.06) |

80.0 (26.67) |

84.9 (29.39) |

82.5 (28.06) |

74.3 (23.5) |

63.1 (17.28) |

50.9 (10.5) |

39.0 (3.89) |

60٫5 (15٫83) |

| الصغرى المتوسطة °ف (°س) | 17.2 (-8.22) |

19.9 (-6.72) |

28.3 (-2.06) |

37.9 (3.28) |

48.1 (8.94) |

57.0 (13.89) |

62.4 (16.89) |

60.7 (15.94) |

52.1 (11.17) |

40.6 (4.78) |

32.6 (0.33) |

22.6 (-5.22) |

40٫0 (4٫44) |

| الصغرى القياسية °ف (°س) | −26 (-32.2) |

−21 (-29.4) |

−6 (-21.1) |

9 (-12.8) |

28 (-2.2) |

37 (2.8) |

44 (6.7) |

36 (2.2) |

30 (-1.1) |

17 (-8.3) |

1 (-17.2) |

−14 (-25.6) |

−26 (−32٫2) |

| هطول inches (mm) | 3.84 (97.5) |

2.96 (75.2) |

3.88 (98.6) |

3.86 (98) |

4.39 (111.5) |

3.85 (97.8) |

3.67 (93.2) |

3.98 (101.1) |

4.13 (104.9) |

3.94 (100.1) |

4.06 (103.1) |

3.60 (91.4) |

46٫16 (1٬172٫5) |

| سقوط الثلج inches (cm) | 14.3 (36.3) |

10.7 (27.2) |

7.7 (19.6) |

1.5 (3.8) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

2.5 (6.4) |

8.4 (21.3) |

45٫1 (114٫6) |

| Avg. precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 11.4 | 10.1 | 11.9 | 11.3 | 12.6 | 11.3 | 9.9 | 10.0 | 9.7 | 9.0 | 10.3 | 11.6 | 129٫1 |

| Avg. snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 6.7 | 5.5 | 4.4 | 1.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.6 | 5.8 | 25٫1 |

| Sunshine hours | 170.5 | 178.0 | 213.9 | 228.0 | 257.3 | 273.0 | 294.5 | 269.7 | 225.0 | 198.4 | 138.0 | 139.5 | 2٬585٫8 |

| Source: NOAA (normals 1971-2000, records 1954-2001),[62] HKO (sun 1961-1990) [63] | |||||||||||||

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

التوزيع السكاني

| التعداد تاريخياً | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| الإحصاء | التعداد | %± | |

| 1800 | 3٬523 | ||

| 1810 | 3٬955 | 12.3% | |

| 1820 | 4٬726 | 19.5% | |

| 1830 | 7٬074 | 49.7% | |

| 1840 | 9٬468 | 33.8% | |

| 1850 | 13٬555 | 43.2% | |

| 1860 | 26٬917 | 98.6% | |

| 1870 | 37٬180 | 38.1% | |

| 1880 | 42٬015 | 13.0% | |

| 1890 | 53٬230 | 26.7% | |

| 1900 | 79٬850 | 50.0% | |

| 1910 | 98٬915 | 23.9% | |

| 1920 | 138٬036 | 39.6% | |

| 1930 | 164٬072 | 18.9% | |

| 1940 | 166٬267 | 1.3% | |

| 1950 | 177٬397 | 6.7% | |

| 1960 | 162٬178 | -8.6% | |

| 1970 | 158٬017 | -2.6% | |

| 1980 | 136٬392 | -13.7% | |

| 1990 | 139٬739 | 2.5% | |

| 2000 | 121٬578 | -13.0% | |

| تقديري 2006 | 124٬512 | [64] | 2.4% |

| Population 1800–1990[65] | |||

الأحياء

الاقتصاد

هارتفورد هي عاصمة صناعة التأمين في الولايات المتحدة، حيث يوجد فيها المقار الرئيسية لأكبر شركات التأمين في الولايات المتحدة.

التعليم

خدمات الطوارئ

الثقافة

الرياضة

التنمية

النقل

الطرق البيرية

السكك الحديدية

الاعلام

معرض الصور

المدن الشقيقة

Hartford features numerous sister cities. They include:

Hertford, England: The town has a population of about 24,000 and serves many commuters to لندن. The town has a country feel only 20 miles (30 km) north of London.

Hertford, England: The town has a population of about 24,000 and serves many commuters to لندن. The town has a country feel only 20 miles (30 km) north of London. Floridia, Italy: A small suburb of Siracusa located on the southeastern coast of the island of Sicily.

Floridia, Italy: A small suburb of Siracusa located on the southeastern coast of the island of Sicily. Thessaloniki, Greece This mediterranean port is Greece's second largest city, with a population approaching 1 million people.

Thessaloniki, Greece This mediterranean port is Greece's second largest city, with a population approaching 1 million people. Mangualde, Portugal: A small town in Centro Region that is very close to the Serra da Estrela Mountains.

Mangualde, Portugal: A small town in Centro Region that is very close to the Serra da Estrela Mountains. Bydgoszcz, Poland: A city in north-central Poland. It is part of the metroplex Bydgoszcz-Toruń with Toruń, only 45 km away, and over 850,000 inhabitants.

Bydgoszcz, Poland: A city in north-central Poland. It is part of the metroplex Bydgoszcz-Toruń with Toruń, only 45 km away, and over 850,000 inhabitants. Caguas, پوِرتو ريكو: A midsized city in central Puerto Rico. The city of Hartford has the highest percentage of individuals with Puerto Rican ancestry in the continental United States.

Caguas, پوِرتو ريكو: A midsized city in central Puerto Rico. The city of Hartford has the highest percentage of individuals with Puerto Rican ancestry in the continental United States. Freetown, Sierra Leone: Capital City of Sierra Leone.

Freetown, Sierra Leone: Capital City of Sierra Leone. Morant Bay, Jamaica: A town in southeastern Jamaica. It was the starting point of the only peasant rebellion in Jamaican history.

Morant Bay, Jamaica: A town in southeastern Jamaica. It was the starting point of the only peasant rebellion in Jamaican history. New Ross, Ireland: A small town on the coast of the Irish Sea, south of Dublin. It is the ancestral home of the Kennedy family.

New Ross, Ireland: A small town on the coast of the Irish Sea, south of Dublin. It is the ancestral home of the Kennedy family. Ocotal, Nicaragua: A large town in northern Nicaragua.

Ocotal, Nicaragua: A large town in northern Nicaragua. João Pessoa, البرازيل: Capital of the State of Paraíba, in the Northeast region of the country.

João Pessoa, البرازيل: Capital of the State of Paraíba, in the Northeast region of the country.

الظهور في الثقافة الشعبية

- Hartford was one of the 23 American cities bombed in the CBS drama Jericho.

- Hartford was the site of episode 3.29 of the documentary television series Gangland on the History Channel about its Los Solidos gang.

- The city was the setting for the Amy Brenneman series Judging Amy, which aired on CBS from 1999–2005.

- Many scenes in the WB/CW series Gilmore Girls take place in Hartford.

- Hartford was the setting for the 2002 movie, Far From Heaven.

- In the Simpsons episode They Saved Lisa's Brain, Homer enters a talent competition in which the winner will receive (as advertised on television) "a free trip to Hawaii". When participants show up for the event, the announcer reveals that the trip is actually to Hartford, Connecticut, claiming that "no one said Hawaii".

- In Stephen King's novel The Mist, Hartford is the only word heard on the radio by protagonist David Drayton after he leaves with a group from the supermarket in his home town.

- Hartford is one of the Eastern seaboard cities shown to be targeted with a nuclear weapon by the antagonist of the video game, Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare.

- In the Kevin Smith written movies Mallrats and Chasing Amy, two different characters played by Jason Lee reference the Hartford Whalers. In Mallrats, Lee's character Brody says, "Breakfasts come and go, Rene. Now Hartford, the Whale? They only beat Vancouver once or twice in a lifetime." In Chasing Amy, Lee's character Banky says, "What difference does it make if I refer to her as a dyke? Or if I call the Whalers a bunch of faggots in the comfort of my own office, far from the sensitive ears of the rest of the world?"

المصادر

- ^ "Mayor Bronin Delivers State of the City Address". City of Hartford. March 13, 2017. Archived from the original on March 27, 2017.

Post Nubila Phoebus – after the clouds, the sun. Our city's motto, written a long time ago, but written for such a time as this

- ^ Burpee, Charles W (1928). History of Hartford County, Connecticut, 1633–1928: being a study of the first makers of the Constitution and the story of their lives, of their descendants and of all who have come. Vol. I. Chicago: S. J. Clarke. p. 41.

- ^ Municipal Register of the City of Hartford. Hartford: The Smith-Linsley Company. 1909. p. 36.

- ^ "State and Municipal Compendium". The Commercial & Financial Chronicle. New York. April 1, 1897. p. 37.

The town and city of Hartford were consolidated on April 1, 1896, and their debts are no longer reported separately

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- ^ "Geographic Names Information System". edits.nationalmap.gov. Retrieved 2023-05-05.

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: هارتفورد، كنتيكت

- ^ "Connecticut: 2010 Population and Housing Unit Counts" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. June 2012. p. 11. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 22, 2017. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- ^ https://portal.ct.gov/about/, Retrieved 2023-01-03.

- ^ https://www.newhavenct.gov/government/about-new-haven/new-haven-s-history, Retrieved 2023-01-03.

- ^ Paul Zielbauer, "Poverty in a Land of Plenty: Can Hartford Ever Recover?" The New York Times, August 26, 2002.

- ^ "Metro Hartford Progress Points" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 6, 2014. Retrieved March 13, 2015.

- ^ "The World According to GaWC 2020". GaWC - Research Network. Globalization and World Cities. Retrieved August 31, 2020.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماة:4 - ^ Bacon, Nick. 2013. "Podunk after Pratt: Place and Placelessness in East Hartford, CT." p. 46–64 in Confronting Urban Legacy: Rediscovering Hartford and New England's Forgotten Cities. Xiangming Chen and Nick Bacon (eds). Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

- ^ Sterner, Daniel (2012). A Guide to Historic Hartford, Connecticut. The History Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-60949-635-7. Retrieved August 16, 2014.

- ^ "House of Hope". The New Netherland Institute. Archived from the original on April 10, 2015. Retrieved April 5, 2015.

- ^ Peterson, Mark. The City-State of Boston. Princeton University Press, 2019, page 48.

- ^ Scaeva (1853). Hartford in the Olden Time, Its First Thirty Years (1st ed.). Hartford: F.A. Brown. pp. 25–36.

- ^ Walsh, Andrew. "Hartford: A Global History." pp. 21–45 in Confronting Urban Legacy: Rediscovering Hartford and New England's Forgotten Cities. Xiangming Chen and Nick Bacon (eds.). Lanham, MD: Lexington Books

- ^ Shuffelton, Frank (1977). Thomas Hooker, 1586–1647. Princeton University Press. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-691-61327-7. Retrieved April 5, 2015.

- ^ Nancy Finlay (September 22, 2020). "Thomas Hooker: Connecticut's Founding Father". ConnecticutHistory.org.

- ^ "The Charter Oak Fell – Today in History: August 21". connecticuthistory.org. Connecticut Humanities. Archived from the original on July 28, 2014. Retrieved August 16, 2014.

- ^ "Hartford Convention | United States history". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on May 7, 2017. Retrieved April 30, 2017.

- ^ "God in America – People – Lyman Beecher". God in America. Archived from the original on April 29, 2017. Retrieved April 30, 2017.

- ^ "Lyman Beecher – Ohio History Central". ohiohistorycentral.org. Archived from the original on May 6, 2017. Retrieved April 30, 2017.

- ^ "Harriet B. Stowe – Ohio History Central". ohiohistorycentral.org. Archived from the original on May 16, 2017. Retrieved April 30, 2017.

- ^ "Harriet Beecher Stowe's Life". harrietbeecherstowecenter.org. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved April 30, 2017.

- ^ "Education & Resources – National Women's History Museum – NWHM". nwhm.org. Archived from the original on November 8, 2016. Retrieved April 30, 2017.

- ^ "Hartford Wide-Awakes – Today in History: July 26". Connecticuthistory.org. Archived from the original on May 1, 2016. Retrieved April 30, 2017.

- ^ Clymer, Floyd. Treasury of Early American Automobiles, 1877–1925 (New York: Bonanza Books, 1950), p.37.

- ^ Hintz, Eric (June 6, 2012). "Samuel Colt ... and Sewing Machines?". O, Say Can You See Blog. National Museum of American History. Archived from the original on June 8, 2015. Retrieved June 8, 2015.

- ^ أ ب Flayderman, Norm (2007). Flayderman's Guide to Antique American Firearms and Their Values. Iola, Wisconsin: F+W Media, Inc. pp. 193–196. ISBN 978-0-89689-455-6. Archived from the original on January 2, 2016. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

- ^ "Invention hot spot: Beginnings of mass production in 19th-century Hartford, Connecticut". invention.smithsonian.org. Jerome and Dorothy Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation, Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on August 19, 2014. Retrieved August 15, 2014.

- ^ Goddard, Stephen B. (December 30, 2008). Colonel Albert Pope and His American Dream Machines: The Life and Times of a Bicycle Tycoon Turned Automotive Pioneer. McFarland. pp. 176–182. ISBN 978-0-7864-4089-4.

- ^ Hamilton, Robert A. (April 12, 1992). "116-Year-Old Company Thrives on Innovation". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 26, 2015. Retrieved April 30, 2017.

- ^ "Record-Breaking Flood at Hartford, Conn". Popular Mechanics. Hearst Magazines. June 1909. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ^ "Hartford Circus Fire: "The Tent's on Fire!" – Who Knew? | ConnecticutHistory.org". connecticuthistory.org. July 6, 2013. Archived from the original on July 7, 2017. Retrieved April 30, 2017.

- ^ Cruz, Jose. "A Decade of Change: Putero Rican Politics in Hartford Connecticut" (PDF). trincoll.edu. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 16, 2016. Retrieved April 29, 2017.

- ^ "Constitution Plaza in Hartford – A History of its Development". Connecticut Historical Society (in الإنجليزية). 2014-11-04. Retrieved 2022-02-16.

- ^ "The 'Four Builds' – The History of Hartford, Connecticut – Connecticut Historical Society". Connecticut Historical Society. December 16, 2014. Archived from the original on January 17, 2017. Retrieved April 30, 2017.

- ^ Archives, T. H. W. (2021-05-06). "Brass Bonanza Silenced: The Demise of the Hartford Whalers". The Hockey Writers (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 2022-02-16.

- ^ "Developer proposes new arena in Hartford" Archived أبريل 13, 2015 at the Wayback Machine AP report on ESPN.com (December 29, 2005)

- ^ Katz, Bruce (2001-04-08). "Escape From Connecticut's Cities". Brookings (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 2022-02-17.

- ^ The estimated population as of 2008 is 124,062 – an increase of 2,484 from the 2000 Census. US Census: Population Finder: hartford city, CT

- ^ "Hartford.Gov – Department of Families, Children, Youth and Recreation" (PDF). hartford.gov. Archived from the original on March 20, 2012.

- ^ "Our History | Riverfront Recapture". Riverfront.org. Archived from the original on October 11, 2018. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ أ ب FELSON, LEONARD. "Rediscover the Connecticut River: Picture a waterfront promenade and new riverside trails to explore. Cross those bridges. Grab an oar. Learn more about the lore". courant.com. Retrieved 2022-02-21.

- ^ Osborn, M. Elizabeth (2010) (in en), Hartford Stage, Continuum, doi:, ISBN 978-0-19-975472-4, https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199754724.001.0001/acref-9780199754724-e-1175, retrieved on 2022-02-21

- ^ Hamad, Michael. "Four Days Of Hip Hop at Trinity International Fest". Courant.com. Archived from the original on December 15, 2017. Retrieved April 30, 2017.

- ^ أ ب Rojas, Rick; Walsh, Mary Williams (2017-08-15). "Hartford, With Its Finances in Disarray, Veers Toward Bankruptcy". The New York Times (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-02-21.

- ^ Condon, Tom (2017-06-09). "For Hartford, bankruptcy not an easy way out". CT Mirror (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 2022-02-21.

- ^ Carlesso, Jenna. "Hartford Hires Bankruptcy Lawyer As City Officials Weigh Options". Courant.com. Archived from the original on July 9, 2017. Retrieved July 9, 2017.

- ^ "Law Firm to Help Hartford Evaluate Restructuring Efforts". NBC Connecticut. Archived from the original on July 9, 2017. Retrieved July 9, 2017.

- ^ Keating, Christopher. "Gov. Malloy Defends Long-Term Hartford Bailout". Courant.com. Archived from the original on October 10, 2018. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- ^ Baker, Mike; Healy, Jack; Rojas, Rick; Sandoval, Edgar; Bosman, Julie; Fawcett, Eliza; Cochrane, Emily; Robertson, Campbell (2022-10-26). "Meet Me Downtown". The New York Times (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-10-28.

- ^ Office, Enter your Company or Top-Level. "DECD: DECD:Connecticut Population, Land Area, and Density by Location". ct.gov. Archived from the original on August 27, 2016. Retrieved April 30, 2017.

- ^ "Population per square mile, 2010". Census.gov. Retrieved April 30, 2017.

- ^ GRANT, STEVE. "Hartford: A City On The River". Courant.com. Archived from the original on April 17, 2016. Retrieved April 30, 2017.

- ^ "Bushnell Park". Archived from the original on 22 June 2007. Retrieved February 15, 2022.

- ^ "Main Street Bridge". Past-inc.org. Archived from the original on June 19, 2012. Retrieved June 9, 2012.

- ^ "Climatography of the United States No. 20: HARTFORD BRADLEY INTL AP, CT" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2010-05-08.

- ^ "Climatological Normals of Hartford". Hong Kong Observatory. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ^ Census data for Hartford, United States Census Bureau. Accessed December 23, 2007.

- ^ [1], U.S. Census Bureau. Accessed January 23, 2008.

وصلات خارجية

- Hartford.gov - Official Hartford website

- Hartford.com - Official tourism website

- Riverfront.org - Riverfront Recapture site

- MetroHartford.com - Chamber of Commerce

- enjoyhartford.com - Greater Hartford Convention & Visitors Bureau

- Hartford, Connecticut: Landmarks ~ History ~ Neighborhoods

- Hartford Advocate

- Hartford Radio and TV History Site

- Hartford travel guide from Wikitravel

- صفحات ذات وسوم إحداثيات غير صحيحة

- CS1: Julian–Gregorian uncertainty

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Missing redirects

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Pages using infobox settlement with possible nickname list

- Pages using infobox settlement with possible motto list

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Use American English from January 2019

- All Wikipedia articles written in American English

- Articles with unsourced statements from December 2022

- Cities in Connecticut

- Populated places in Hartford County, Connecticut

- Hartford, Connecticut

- Populated places on the Connecticut River

- Populated places established in 1637

- مدن كنتيكت