گاڤريلو پرنسيپ

گاڤريلو پرنسيپ Gavrilo Princip | |

|---|---|

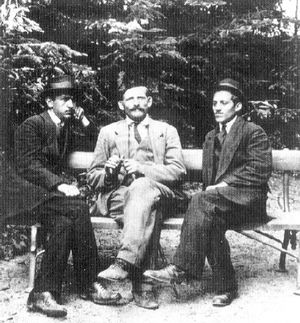

گاڤريلو پرنسيپ في زنزانته في حصرن ترزين | |

| وُلِدَ | 25 يوليو 1894 |

| توفي | 28 أبريل 1918 (aged 23) |

| سبب الوفاة | السل |

| المثوى | Vidovdan Heroes Chapel, سراييڤو 43°52′0.76″N 18°24′38.88″E / 43.8668778°N 18.4108000°E |

| اللقب | اغتيال الأرشدوق فرانتس فرديناند من النمسا، الذي أسهم في اندلاع الحرب العالمية الأولى |

| التوقيع | |

| |

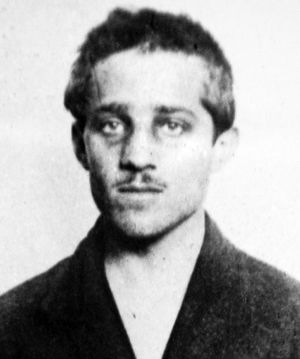

گاڤريلو پرنسيپ (Gavrilo Princip ؛ سيريلية صربية: Гаврило Принцип؛ تـُنطق [ɡǎʋrilo prǐntsip]؛ 25 يوليو 1894 – 28 أبريل 1918) كان عضواً من صرب البوسنة في البوسنة الفتاة التي كانت تسعى إلى إنهاء الحكم النمساوي-المجري في البوسنة والهرسك. وفي عمر التاسعة عشر، قام باغتيال الأرشدوق فرانتس فرديناند من النمسا وزوجة الأرشدوق، صوفي، دوقة هوهنبرگ، في سراييڤو في 28 يونيو 1914. پرنسيپ وشركاؤه ألقِيَ القبض عليهم وثبت تورطهم كجمعية سرية وطنية، كانت قد بدأت أزمة يوليو وأدت إلى اندلاع الحرب العالمية الأولى.

وفي محاكمته، قال پرنسيپ: "أنا وطني يوغسلاڤي، أهدف لتوحيد كل اليوغسلاڤ، ولا يهمني شكل الدولة، ولكنها لابد أن تتحرر من النمسا."[1] حـُكِم على پرنسيپ بالسجن عشرين عاماً، وهي أقصى عقوبة لسنه، وسـُجـِن في حصن ترزين. وقد توفي في 28 أبريل 1918 بالسل الذي فاقمه سوء أحوال السجن التي تسببت قبل وفاته في بتر يده اليمنى.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

النشأة

Gavrilo Princip was born in the remote hamlet of أوبلياي، بالقرب من بوسانسكو گراهوڤو, on 25 July [ن.ق. 13 July] 1894. He was the second of his parents' nine children, six of whom died in infancy. Princip's mother Marija wanted to name him after her late brother Špiro, but he was named Gavrilo at the insistence of a local Eastern Orthodox priest, who claimed that naming the sickly infant after the Archangel Gabriel would help him survive.[2]

A Serb family, the Princips had lived in northwestern Bosnia for many centuries[3] and adhered to the Serbian Orthodox Christian faith.[4] Princip's parents, Petar and Marija (née Mićić), were poor farmers who lived off the little land that they owned.[5] They belonged to a class of Christian peasants known as kmeti (serfs), who were often oppressed by their Muslim landlords.[6]

Petar, who insisted on "strict correctness," never drank or swore and was ridiculed by his neighbours as a result.[5] In his youth, he fought in the Herzegovina Uprising against the Ottoman Empire.[7] Following the revolt, he returned to being a farmer in the Grahovo valley, where he worked approximately 4 acres (1.6 ha; 0.0063 sq mi) of land and was forced to give a third of his income to his landlord. In order to supplement his income and feed his family, he resorted to transporting mail and passengers across the mountains between northwestern Bosnia and Dalmatia.[8]

In 1913, while Princip was staying in Sarajevo, Austria-Hungary declared a state of emergency, implemented martial law, seized control of all schools, and prohibited all Serb cultural organizations.[9]

اغتيال الأرشدوق فرانتس فرديناند

On 28 June 1914, Princip participated in the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and his wife, Duchess Sophie Chotek. The royal couple arrived in Sarajevo by train shortly before 10 a.m. and rode in the third car of a six-car motorcade towards Town Hall.[10] Their car's top was rolled back in order to allow the crowds a good view of its occupants.[11]

إلقاء القبض عليه والمحاكمة

Princip attempted to shoot himself, but the pistol was wrestled from his hand before he had a chance to fire another shot.[12] At his trial, he said he regretted the killing of the Duchess but that he was proud of what he had done[13] and stated that: "I am a Yugoslav nationalist, aiming for the unification of all Yugoslavs, and I do not care what form of state, but it must be freed from Austria."[1] The Black Hand was implicated in the assassination which led Austria-Hungary to issue a démarche to Serbia known as the July Ultimatum which led up to the outbreak of World War I.[14]

الحبس والوفاة

Princip was chained to a wall in solitary confinement في حصن ترزين، حيث عاش في ظروف قاسية وأصيب بالسل.[15][14] The disease ate away his bones so badly that his right arm had to be amputated.[16] In January 1916, Princip unsuccessfully attempted to hang himself with a towel.[17] From February to June 1916, Princip met with Martin Pappenheim, a psychiatrist in the Austro-Hungarian army, four times.[17] Pappenheim wrote that Princip believed the World War was bound to happen, independent of his actions, and that he "cannot feel himself responsible for the catastrophe."[15]

Gavrilo Princip died on 28 April 1918, three years and ten months after the assassination. At the time of his death, weakened by malnutrition and disease, he weighed around 40 kilograms (88 lb; 6 st 4 lb).[18]

Fearing his bones might become relics for Slavic nationalists, Princip's prison guards secretly took the body to an unmarked grave, but a Czech soldier assigned to the burial remembered the location, and in 1920 Princip and the other "Heroes of Vidovdan" were exhumed and brought to Sarajevo, where they were buried together beneath a chapel "built to commemorate for eternity our Serb heroes" at the Saint Archangels Cemetery[19] which includes a citation from the Montenegrin poet Njegoš: "Blessed is he who lives forever. He had something to be born for."[20]

ذكراه

Princip's legacy is still disputed. He is celebrated as a hero by Serbs but regarded as a terrorist by many Bosniaks.[21]

نصب تذكارية وتخليد

انظر أيضاً

المراجع

- ^ أ ب Dedijer 1966, p. 341.

- ^ Dedijer 1966, pp. 187–188.

- ^ Fromkin 2007, pp. 121–122.

- ^ Roider 2005, p. 935.

- ^ أ ب Fabijančić 2010, p. xxii.

- ^ Schlesser 2005, p. 93.

- ^ Kidner et al. 2013, p. 756.

- ^ Schlesser 2005, p. 95.

- ^ Schlesser 2005, p. 97.

- ^ Burns, Tracy. "'June 28, 1914: The first attempt'". www.private-prague-guide.com/. Archived from the original on 27 January 2015. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ^ Donnelley 2012, p. 33.

- ^ Duffy, Michael (22 August 2009). "Who's Who - Gavrilo Princip". www.firstworldwar.com. Archived from the original on 14 August 2019. Retrieved 2019-09-08.

- ^ "Man accused of murdering Archduke Ferdinand goes on trial – archive, 1914". The Guardian (in الإنجليزية البريطانية). 2017-10-17. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 4 July 2019. Retrieved 2019-07-04.

- ^ أ ب Johnson 1989, pp. 52-54.

- ^ أ ب "Gavrilo Princip Speaks: 1916 Conversations with Martin Pappenheim | Carl Savich" (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 29 August 2013. Archived from the original on 4 July 2019. Retrieved 2019-07-04.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةtelegraph - ^ أ ب Pappenheim, Martin (1916). "Gavrilo Princip, a participant in the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand". The British Library. Archived from the original on 1 May 2017. Retrieved 2019-07-06.

- ^ "101st Anniversary of the Sarajevo Assassination that caused the World War I". Sarajevo Times (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). June 29, 2015. Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved February 14, 2020.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; فبراير 15, 2020 suggested (help) - ^ Pokop.ba. "Sveti Arhangeli Georgije i Gavrilo" (in Bosnian). Archived from the original on 5 June 2019. Retrieved 2019-07-12.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "GAVRILO PRINCIP – SOME THINGS NEVER CHANGE". Meet the Slavs. 29 يونيو 2014. Archived from the original on 26 December 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- ^ Beasley-Murray, Benjamin (26 June 2014). "Gavrilo Princip's Legacy Still Contested". Institute for War and Peace Reporting (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on 4 July 2019. Retrieved 2019-07-04.

Bibliography

- Belfield, Richard (2011). A Brief History of Hitmen and Assassinations. Constable & Robinson, Ltd. ISBN 978-1-849018-05-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Clark, Christopher (2013). The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06219-922-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dedijer, Vladimir (1966). The Road to Sarajevo. Simon and Schuster. ASIN B0007DMDI2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Donnelley, Paul (2012). Assassination!. ISBN 978-1-908963-03-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fabijančić, Tony (2010). Bosnia: In the Footsteps of Gavrilo Princip. Edmonton: University of Alberta. ISBN 978-0-88864-519-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fromkin, David (2007). Europe's Last Summer: Who Started the Great War in 1914?. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-307-42578-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gilbert, Martin (1995). The First World War. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-637666-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Glenny, Misha (2012). The Balkans: Nationalism, War, and the Great Powers, 1804–2012: New and Updated (revised ed.). Penguin. ISBN 978-1-77089-274-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Johnson, Lonnie (1989). Introducing Austria: A short history. ISBN 0-929497-03-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kidner, Frank; Bucur, Maria; Mathisen, Ralph; McKee, Sally; Weeks, Theodore (2013). Making Europe: The Story of the West Since 1550. Vol. 2 (2th ed.). Boston: Wadsworth Cengage. ISBN 978-1-111-84134-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Malcolm, Noel (1994). Bosnia: A Short History. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-5520-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Remak, Joachim (1959). Sarajevo: The Story of a Political Murder. Criterion. ASIN B001L4NB5U.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Roider, Karl (2005). "Princip, Gavrilo (1894–1918)". In Tucker, Spencer C.; Roberts, Priscilla Mary (eds.). The Encyclopedia of World War I : A Political, Social, and Military History. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-420-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Schlesser, Steven (2005). The Soldier, the Builder & the Diplomat. Seattle: Cune Press. ISBN 978-1-885942-07-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stokesbury, James (1981). A Short History of World War I. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-061763-61-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

للاستزادة

- Bataković, Dušan T., ed. (2005). Histoire du peuple serbe [History of the Serbian People] (in French). Lausanne: L’Age d’Homme. ISBN 978-2-8251-1958-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Brescia, Anthony M (1965). The Role Gavrilo Princip in the Greater Serbian Movement.

- Butcher, Tim (2014). The Trigger: Hunting the Assassin who Brought the World to War. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 978-0-7011-8793-4.

- Ljubibratić, Dragoslav (1959). Gavrilo Princip. Nolit.

- Savary, Michèle (2004). Sarajevo 1914: vie et mort de Gavrilo Princip. L'AGE D'HOMME. ISBN 978-2-8251-1891-7.

- Villiers, Peter (2010). Gavrila Princip: The Assassin Who Started the First World War. Unknown Publisher. ISBN 978-0-9566211-0-8.

- Wolfson, Robert; Laver, John (2001-12-30). Years of Change, European History 1890–1990 (3 ed.). Hodder Murray. p. 117. ISBN 0-340-77526-2.

- Gavrilo Princips Bekenntnisse. Zwei Manuscripte Princips, Aufzeichungen Seines Gefängnispsychiaters Dr. Pappenheim Aus Gesprächen Von Feber ... Über Das Attentat, Princips Leben und Seine Politischen und Sozialen Anschauungen. Mit Einführung und Kommentar Von R.P. Wien: Lechner und Son. 1926.

وصلات خارجية

- CS1 الإنجليزية البريطانية-language sources (en-gb)

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- CS1 errors: archive-url

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Biography with signature

- Articles containing صربية-language text

- مواليد 1894

- وفيات 1918

- اغتيال الأرشدوق فرانتس فرديناند من النمسا

- Bosnia and Herzegovina murderers

- Former Serbian Orthodox Christians

- أشخاص من بوسانسكو گراهوڤو

- People from the Condominium of Bosnia and Herzegovina

- صرب البوسنة والهرسك

- ملحدو البوسنة والهرسك

- Bosnia and Herzegovina people who died in prison custody

- Bosnia and Herzegovina people of World War I

- أسباب الحرب العالمية الأولى

- مجرمو القرن العشرين

- وفيات بالسل في القرن العشرين

- Infectious disease deaths in Czechoslovakia

- Serb nationalist assassins

- Amputees

- Prisoners who died in Austrian detention

- البوسنة الفتاة

- Yugoslavism

- Austro-Hungarian rebels

- Burials at Saint Archangels Cemetery, Sarajevo