لانثانيد

| جزء من سلسلة عن |

| الجدول الدوري |

|---|

سلسلة اللانثـنيدات تتكون من 14 عنصر أرضي نادر تبدأ من سيريوم إلى لوتيتيوم في الجدول الدوري ، بالأرقام الذرية من 58 إلى 71 . وترجع تسمية سلسلة اللانثينيدات إلى عنصر اللانثانوم رغم أنه لا يوجد فيها . وتلى سلسة اللانثينيدات سلسة الأكتينيدات .

وتكون سلسلة اللانثينيدات هى السلسلة التى يكون فيها المدار f ممتلئ جزئيا أو كليا . بينما تكون المدارات الخارجية p و d فارغة . وحيث ان المدار f ليس نشيط كيميائيا مثل المدارات s و d و p ، فإن عناصر سلسلة اللانثينيدات تكون متشابها كيميائيا .

ويتم وضع سلسة اللانثينيدات تحت الجدول الدوري كما لو كانت تذييل له . بينما يوضح الجدول الدوري الطويل المكان الفعلى لمجموعة اللانثينيدات .

قالب:Periodic table (lanthanides)

| الرقم الذري | الإسم | الرمز |

|---|---|---|

| 58 | سيريوم | Ce |

| 59 | براسيوديميوم | Pr |

| 60 | نيوديوم | Nd |

| 61 | بروميثيوم | Pm |

| 62 | ساماريوم | Sm |

| 63 | يوروبيوم | Eu |

| 64 | جادولينيوم | Gd |

| 65 | تريبيوم | Tb |

| 66 | ديسبروسيوم | Dy |

| 67 | هولميوم | Ho |

| 68 | إبريوم | Er |

| 69 | ثوليوم | Tm |

| 70 | اِيتربيوم | Yb |

| 71 | لوتيتيوم | Lu |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Physical properties of the elements

| Chemical element | La | Ce | Pr | Nd | Pm | Sm | Eu | Gd | Tb | Dy | Ho | Er | Tm | Yb | Lu |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atomic number | 57 | 58 | 59 | 60 | 61 | 62 | 63 | 64 | 65 | 66 | 67 | 68 | 69 | 70 | 71 |

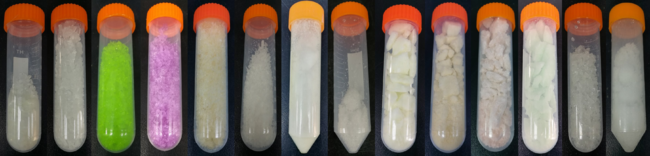

| Image |  |

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| Density (g/cm3) | 6.162 | 6.770 | 6.77 | 7.01 | 7.26 | 7.52 | 5.244 | 7.90 | 8.23 | 8.540 | 8.79 | 9.066 | 9.32 | 6.90 | 9.841 |

| Melting point (°C) | 920 | 795 | 935 | 1024 | 1042 | 1072 | 826 | 1312 | 1356 | 1407 | 1461 | 1529 | 1545 | 824 | 1652 |

| Boiling point (°C) | 3464 | 3443 | 3520 | 3074 | 3000 | 1794 | 1529 | 3273 | 3230 | 2567 | 2720 | 2868 | 1950 | 1196 | 3402 |

| Atomic electron configuration (gas phase)* |

5d1 | 4f15d1 | 4f3 | 4f4 | 4f5 | 4f6 | 4f7 | 4f75d1 | 4f9 | 4f10 | 4f11 | 4f12 | 4f13 | 4f14 | 4f145d1 |

| Metal lattice (RT) | dhcp | fcc | dhcp | dhcp | dhcp | ** | bcc | hcp | hcp | hcp | hcp | hcp | hcp | fcc | hcp |

| Metallic radius (pm) | 162 | 181.8 | 182.4 | 181.4 | 183.4 | 180.4 | 208.4 | 180.4 | 177.3 | 178.1 | 176.2 | 176.1 | 175.9 | 193.3 | 173.8 |

| Resistivity at 25 °C (μΩ·cm) | 57–80 20 °C |

73 | 68 | 64 | 88 | 90 | 134 | 114 | 57 | 87 | 87 | 79 | 29 | 79 | |

| Magnetic susceptibility χmol /10−6(cm3·mol−1) |

+95.9 | +2500 (β) | +5530(α) | +5930 (α) | +1278(α) | +30900 | +185000 (350 K) |

+170000 (α) | +98000 | +72900 | +48000 | +24700 | +67 (β) | +183 |

* Between initial Xe and final 6s2 electronic shells

** Sm has a close packed structure like most of the lanthanides but has an unusual 9 layer repeat

Gschneider and Daane (1988) attribute the trend in melting point which increases across the series, (lanthanum (920 °C) – lutetium (1622 °C)) to the extent of hybridization of the 6s, 5d, and 4f orbitals. The hybridization is believed to be at its greatest for cerium, which has the lowest melting point of all, 795 °C.[1] The lanthanide metals are soft; their hardness increases across the series.[2] Europium stands out, as it has the lowest density in the series at 5.24 g/cm3 and the largest metallic radius in the series at 208.4 pm. It can be compared to barium, which has a metallic radius of 222 pm. It is believed that the metal contains the larger Eu2+ ion and that there are only two electrons in the conduction band. Ytterbium also has a large metallic radius, and a similar explanation is suggested.[2] The resistivities of the lanthanide metals are relatively high, ranging from 29 to 134 μΩ·cm. These values can be compared to a good conductor such as aluminium, which has a resistivity of 2.655 μΩ·cm. With the exceptions of La, Yb, and Lu (which have no unpaired f electrons), the lanthanides are strongly paramagnetic, and this is reflected in their magnetic susceptibilities. Gadolinium becomes ferromagnetic at below 16 °C (Curie point). The other heavier lanthanides – terbium, dysprosium, holmium, erbium, thulium, and ytterbium – become ferromagnetic at much lower temperatures.[3]

Chemistry and compounds

| Chemical element | La | Ce | Pr | Nd | Pm | Sm | Eu | Gd | Tb | Dy | Ho | Er | Tm | Yb | Lu |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atomic number | 57 | 58 | 59 | 60 | 61 | 62 | 63 | 64 | 65 | 66 | 67 | 68 | 69 | 70 | 71 |

| Ln3+ electron configuration*[4] | 4f0 | 4f1 | 4f2 | 4f3 | 4f4 | 4f5 | 4f6 | 4f7 | 4f8 | 4f9 | 4f10 | 4f11 | 4f12 | 4f13 |

4f14 |

| Ln3+ radius (pm)[2] | 103 | 102 | 99 | 98.3 | 97 | 95.8 | 94.7 | 93.8 | 92.3 | 91.2 | 90.1 | 89 | 88 | 86.8 | 86.1 |

| Ln4+ ion color in aqueous solution[5] | — | Orange-yellow | Yellow | Blue-violet | — | — | — | — | Red-brown | Orange-yellow | — | — | — | — | — |

| Ln3+ ion color in aqueous solution[4] | Colorless | Colorless | Green | Violet | Pink | Pale yellow | Colorless | Colorless | V. pale pink | Pale yellow | Yellow | Rose | Pale green | Colorless | Colorless |

| Ln2+ ion color in aqueous solution[2] | — | — | — | — | — | Blood red | Colorless | — | — | — | — | — | Violet-red | Yellow-green | — |

* Not including initial [Xe] core

| Oxidation state | 57 | 58 | 59 | 60 | 61 | 62 | 63 | 64 | 65 | 66 | 67 | 68 | 69 | 70 | 71 |

| +2 | Sm2+ | Eu2+ | Tm2+ | Yb2+ | |||||||||||

| +3 | La3+ | Ce3+ | Pr3+ | Nd3+ | Pm3+ | Sm3+ | Eu3+ | Gd3+ | Tb3+ | Dy3+ | Ho3+ | Er3+ | Tm3+ | Yb3+ | Lu3+ |

| +4 | Ce4+ | Pr4+ | Nd4+ | Tb4+ | Dy4+ |

Effect of 4f orbitals

Going across the lanthanides in the periodic table, the 4f orbitals are usually being filled. The effect of the 4f orbitals on the chemistry of the lanthanides is profound and is the factor that distinguishes them from the transition metals. There are seven 4f orbitals, and there are two different ways in which they are depicted: as a "cubic set" or as a general set. The cubic set is fz3, fxz2, fyz2, fxyz, fz(x2−y2), fx(x2−3y2) and fy(3x2−y2). The 4f orbitals penetrate the [Xe] core and are isolated, and thus they do not participate in bonding. This explains why crystal field effects are small and why they do not form π bonds.[4] As there are seven 4f orbitals, the number of unpaired electrons can be as high as 7, which gives rise to the large magnetic moments observed for lanthanide compounds.

Measuring the magnetic moment can be used to investigate the 4f electron configuration, and this is a useful tool in providing an insight into the chemical bonding.[8] The lanthanide contraction, i.e. the reduction in size of the Ln3+ ion from La3+ (103 pm) to Lu3+ (86.1 pm), is often explained by the poor shielding of the 5s and 5p electrons by the 4f electrons.[4]

The electronic structure of the lanthanide elements, with minor exceptions, is [Xe]6s24fn. The chemistry of the lanthanides is dominated by the +3 oxidation state, and in LnIII compounds the 6s electrons and (usually) one 4f electron are lost and the ions have the configuration [Xe]4fm.[9] All the lanthanide elements exhibit the oxidation state +3. In addition, Ce3+ can lose its single f electron to form Ce4+ with the stable electronic configuration of xenon. Also, Eu3+ can gain an electron to form Eu2+ with the f7 configuration that has the extra stability of a half-filled shell. Other than Ce(IV) and Eu(II), none of the lanthanides are stable in oxidation states other than +3 in aqueous solution. Promethium is effectively a man-made element, as all its isotopes are radioactive with half-lives shorter than 20 years.

In terms of reduction potentials, the Ln0/3+ couples are nearly the same for all lanthanides, ranging from −1.99 (for Eu) to −2.35 V (for Pr). Thus these metals are highly reducing, with reducing power similar to alkaline earth metals such as Mg (−2.36 V).[2]

Lanthanide oxidation states

| Chemical element | La | Ce | Pr | Nd | Pm | Sm | Eu | Gd | Tb | Dy | Ho | Er | Tm | Yb | Lu |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atomic number | 57 | 58 | 59 | 60 | 61 | 62 | 63 | 64 | 65 | 66 | 67 | 68 | 69 | 70 | 71 |

| electron configuration above [Xe] core |

5d16s2 | 4f15d16s2 | 4f36s2 | 4f46s2 | 4f56s2 | 4f66s2 | 4f76s2 | 4f75d16s2 | 4f96s2 | 4f106s2 | 4f116s2 | 4f126s2 | 4f136s2 | 4f146s2 | 4f145d16s2 |

| E° Ln4+/Ln3+ | 1.72 | 3.2 | 3.1 | ||||||||||||

| E° Ln3+/Ln2+ | −2.6 | −1.55 | −0.35 | −2.5 | −2.3 | −1.05 | |||||||||

| E° Ln3+/Ln | −2.38 | −2.34 | −2.35 | −2.32 | −2.29 | −2.30 | −1.99 | −2.28 | −2.31 | −2.29 | −2.33 | −2.32 | −2.32 | −2.22 | −2.30 |

| 1st Ionization energy (kJ·mol−1) |

538 | 541 | 522 | 530 | 536 | 542 | 547 | 595 | 569 | 567 | 574 | 581 | 589 | 603 | 513 |

| 2nd Ionization energy (kJ·mol−1) |

1067 | 1047 | 1018 | 1034 | 1052 | 1068 | 1085 | 1172 | 1112 | 1126 | 1139 | 1151 | 1163 | 1175 | 1341 |

| 1st + 2nd Ionization energy (kJ·mol−1) |

1605 | 1588 | 1540 | 1564 | 1588 | 1610 | 1632 | 1767 | 1681 | 1693 | 1713 | 1732 | 1752 | 1778 | 1854 |

| 3rd Ionization energy (kJ·mol−1) |

1850 | 1940 | 2090 | 2128 | 2140 | 2285 | 2425 | 1999 | 2122 | 2230 | 2221 | 2207 | 2305 | 2408 | 2054 |

| 1st + 2nd + 3rd Ionization energy (kJ·mol−1) |

3455 | 3528 | 3630 | 3692 | 3728 | 3895 | 4057 | 3766 | 3803 | 3923 | 3934 | 3939 | 4057 | 4186 | 3908 |

| 4th Ionization energy (kJ·mol−1) |

4819 | 3547 | 3761 | 3900 | 3970 | 3990 | 4120 | 4250 | 3839 | 3990 | 4100 | 4120 | 4120 | 4203 | 4370 |

The ionization energies for the lanthanides can be compared with aluminium. In aluminium the sum of the first three ionization energies is 5139 kJ·mol−1, whereas the lanthanides fall in the range 3455 – 4186 kJ·mol−1. This correlates with the highly reactive nature of the lanthanides.

Hydrides

| Chemical element | La | Ce | Pr | Nd | Pm | Sm | Eu | Gd | Tb | Dy | Ho | Er | Tm | Yb | Lu |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atomic number | 57 | 58 | 59 | 60 | 61 | 62 | 63 | 64 | 65 | 66 | 67 | 68 | 69 | 70 | 71 |

| Metal lattice (RT) | dhcp | fcc | dhcp | dhcp | dhcp | r | bcc | hcp | hcp | hcp | hcp | hcp | hcp | hcp | hcp |

| Dihydride[10] | LaH2+x | CeH2+x | PrH2+x | NdH2+x | SmH2+x | EuH2 o "salt like" |

GdH2+x | TbH2+x | DyH2+x | HoH2+x | ErH2+x | TmH2+x | YbH2+x o, fcc "salt like" |

LuH2+x | |

| Structure | CaF2 | CaF2 | CaF2 | CaF2 | CaF2 | CaF2 | *PbCl2[11] | CaF2 | CaF2 | CaF2 | CaF2 | CaF2 | CaF2 | CaF2 | |

| metal sub lattice | fcc | fcc | fcc | fcc | fcc | fcc | o | fcc | fcc | fcc | fcc | fcc | fcc | o fcc | fcc |

| Trihydride[10] | LaH3−x | CeH3−x | PrH3−x | NdH3−x | SmH3−x | EuH3−x[12] | GdH3−x | TbH3−x | DyH3−x | HoH3−x | ErH3−x | TmH3−x | LuH3−x | ||

| metal sub lattice | fcc | fcc | fcc | hcp | hcp | hcp | fcc | hcp | hcp | hcp | hcp | hcp | hcp | hcp | hcp |

| Trihydride properties transparent insulators (color where recorded) |

red | bronze to grey[13] | PrH3−x fcc | NdH3−x hcp | golden greenish[14] | EuH3−x fcc | GdH3−x hcp | TbH3−x hcp | DyH3−x hcp | HoH3−x hcp | ErH3−x hcp | TmH3−x hcp | LuH3−x hcp |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Halides

| Chemical element | La | Ce | Pr | Nd | Pm | Sm | Eu | Gd | Tb | Dy | Ho | Er | Tm | Yb | Lu |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atomic number | 57 | 58 | 59 | 60 | 61 | 62 | 63 | 64 | 65 | 66 | 67 | 68 | 69 | 70 | 71 |

| Tetrafluoride | CeF4 | PrF4 | NdF4 | TbF4 | DyF4 | ||||||||||

| Color m.p. °C | white dec | white dec | white dec | ||||||||||||

| Structure C.N. | UF4 8 | UF4 8 | UF4 8 | ||||||||||||

| Trifluoride | LaF3 | CeF3 | PrF3 | NdF3 | PmF3 | SmF3 | EuF3 | GdF3 | TbF3 | DyF3 | HoF3 | ErF3 | TmF3 | YbF3 | LuF3 |

| Color m.p. °C | white 1493[18] | white 1430 | green 1395 | violet 1374 | green 1399 | white 1306 | white 1276 | white 1231 | white 1172 | green 1154 | pink 1143 | pink 1140 | white 1158 | white 1157 | white 1182 |

| Structure C.N. | LaF3 9 | LaF3 9 | LaF3 9 | LaF3 9 | LaF3 9 | YF3 8 | YF3 8 | YF3 8 | YF3 8 | YF3 8 | YF3 8 | YF3 8 | YF3 8 | YF3 8 | YF3 8 |

| Trichloride | LaCl3 | CeCl3 | PrCl3 | NdCl3 | PmCl3 | SmCl3 | EuCl3 | GdCl3 | TbCl3 | DyCl3 | HoCl3 | ErCl3 | TmCl3 | YbCl3 | LuCl3 |

| Color m.p. °C | white 858 | white 817 | green 786 | mauve 758 | green 786 | yellow 682 | yellow dec | white 602 | white 582 | white 647 | yellow 720 | violet 776 | yellow 824 | white 865 | white 925 |

| Structure C.N. | UCl3 9 | UCl3 9 | UCl3 9 | UCl3 9 | UCl3 9 | UCl3 9 | UCl3 9 | UCl3 9 | PuBr3 8 | PuBr3 8 | YCl3 6 | YCl3 6 | YCl3 6 | YCl3 6 | YCl3 6 |

| Tribromide | LaBr3 | CeBr3 | PrBr3 | NdBr3 | PmF3 | SmBr3 | EuBr3 | GdBr3 | TbBr3 | DyBr3 | HoBr3 | ErBr3 | TmBr3 | YbBr3 | LuBr3 |

| Color m.p. °C | white 783 | white 733 | green 691 | violet 682 | green 693 | yellow 640 | grey dec | white 770 | white 828 | white 879 | yellow 919 | violet 923 | white 954 | white dec | white 1025 |

| Structure C.N. | UCl3 9 | UCl3 9 | UCl3 9 | PuBr3 8 | PuBr3 8 | PuBr3 8 | PuBr3 8 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Triiodide | LaI3 | CeI3 | PrI3 | NdI3 | PmI3 | SmI3 | EuI3 | GdI3 | TbI3 | DyI3 | HoI3 | ErI3 | TmI3 | YbI3 | LuI3 |

| Color m.p. °C | yellow 766 | green 738 | green 784 | green 737 | orange 850 | dec. | yellow 925 | 957 | green 978 | yellow 994 | violet 1015 | yellow 1021 | white dec | brown 1050 | |

| Structure C.N. | PuBr3 8 | PuBr3 8 | PuBr3 8 | PuBr3 8 | BiI3 6 | BiI3 6 | BiI3 6 | BiI3 6 | BiI3 6 | BiI3 6 | BiI3 6 | BiI3 6 | BiI3 6 | BiI3 6 | |

| Difluoride | SmF2 | EuF2 | YbF2 | ||||||||||||

| Color m.p. °C | purple 1417 | yellow 1416 | grey | ||||||||||||

| Structure C.N. | CaF2 8 | CaF2 8 | CaF2 8 | ||||||||||||

| Dichloride | NdCl2 | SmCl2 | EuCl2 | DyCl2 | TmCl2 | YbCl2 | |||||||||

| Color m.p. °C | green 841 | brown 859 | white 731 | black dec. | green 718 | green 720 | |||||||||

| Structure C.N. | PbCl2 9 | PbCl2 9 | PbCl2 9 | SrBr2 | SrI2 7 | SrI2 7 | |||||||||

| Dibromide | NdBr2 | SmBr2 | EuBr2 | DyBr2 | TmBr2 | YbBr2 | |||||||||

| Color m.p. °C | green 725 | brown 669 | white 731 | black | green | yellow 673 | |||||||||

| Structure C.N. | PbCl2 9 | SrBr2 8 | SrBr2 8 | SrI2 7 | SrI2 7 | SrI2 7 | |||||||||

| Diiodide | LaI2 metallic |

CeI2 metallic |

PrI2 metallic |

NdI2 high pressure metallic |

SmI2 | EuI2 | GdI2 metallic |

DyI2 | TmI2 | YbI2 | |||||

| Color m.p. °C | bronze 808 | bronze 758 | violet 562 | green 520 | green 580 | bronze 831 | purple 721 | black 756 | yellow 780 | Lu | |||||

| Structure C.N. | CuTi2 8 | CuTi2 8 | CuTi2 8 | SrBr2 8 CuTi2 8 |

EuI2 7 | EuI2 7 | 2H-MoS2 6 | CdI2 6 | CdI2 6 | ||||||

| Ln7I12 | La7I12 | Pr7I12 | ' | Tb7I12 | |||||||||||

| Sesquichloride | La2Cl3 | Gd2Cl3 | Tb2Cl3 | Tm2Cl3 | Lu2Cl3 | ||||||||||

| Structure | Gd2Cl3 | Gd2Cl3 | |||||||||||||

| Sesquibromide | Gd2Br3 | Tb2Br3 | |||||||||||||

| Structure | Gd2Cl3 | Gd2Cl3 | |||||||||||||

| Monoiodide | LaI[19] | ||||||||||||||

| Structure | NiAs type |

| Application | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Catalytic converters | 45% |

| Petroleum refining catalysts | 25% |

| Permanent magnets | 12% |

| Glass polishing and ceramics | 7% |

| Metallurgical | 7% |

| Phosphors | 3% |

| Other | 1% |

The complex Gd(DOTA) is used in magnetic resonance imaging.

| Donor | Excitation⇒Emission λ (nm) | Acceptor | Excitation⇒Emission λ (nm) | Stoke's Shift (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eu3+ | 340⇒615 | Allophycocyanin | 615⇒660 | 320 |

| Tb3+ | 340⇒545 | Phycoerythrin | 545⇒575 | 235 |

Possible medical uses

Currently there is research showing that lanthanide elements can be used as anticancer agents. The main role of the lanthanides in these studies is to inhibit proliferation of the cancer cells. Specifically cerium and lanthanum have been studied for their role as anti-cancer agents.

One of the specific elements from the lanthanide group that has been tested and used is cerium (Ce). There have been studies that use a protein-cerium complex to observe the effect of cerium on the cancer cells. The hope was to inhibit cell proliferation and promote cytotoxicity.[20] Transferrin receptors in cancer cells, such as those in breast cancer cells and epithelial cervical cells, promote the cell proliferation and malignancy of the cancer.[20] Transferrin is a protein used to transport iron into the cells and is needed to aid the cancer cells in DNA replication. Transferrin acts as a growth factor for the cancerous cells and is dependent on iron. Cancer cells have much higher levels of transferrin receptors than normal cells and are very dependent on iron for their proliferation.[20]

Cerium has shown results as an anti-cancer agent due to its similarities in structure and biochemistry to iron. Cerium may bind in the place of iron on to the transferrin and then be brought into the cancer cells by transferrin-receptor mediated endocytosis.[20] The cerium binding to the transferrin in place of the iron inhibits the transferrin activity in the cell. This creates a toxic environment for the cancer cells and causes a decrease in cell growth. This is the proposed mechanism for cerium's effect on cancer cells, though the real mechanism may be more complex in how cerium inhibits cancer cell proliferation. Specifically in HeLa cancer cells studied in vitro, cell viability was decreased after 48 to 72 hours of cerium treatments. Cells treated with just cerium had decreases in cell viability, but cells treated with both cerium and transferrin had more significant inhibition for cellular activity.[20]

Another specific element that has been tested and used as an anti-cancer agent is lanthanum, more specifically lanthanum chloride (LaCl3). The lanthanum ion is used to affect the levels of let-7a and microRNAs miR-34a in a cell throughout the cell cycle. When the lanthanum ion was introduced to the cell in vivo or in vitro, it inhibited the rapid growth and induced apoptosis of the cancer cells (specifically cervical cancer cells). This effect was caused by the regulation of the let-7a and microRNAs by the lanthanum ions.[21] The mechanism for this effect is still unclear but it is possible that the lanthanum is acting in a similar way as the cerium and binding to a ligand necessary for cancer cell proliferation.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Biological effects

Due to their sparse distribution in the earth's crust and low aqueous solubility, the lanthanides have a low availability in the biosphere, and for a long time were not known to naturally form part of any biological molecules. In 2007 a novel methanol dehydrogenase that strictly uses lanthanides as enzymatic cofactors was discovered in a bacterium from the phylum Verrucomicrobia, Methylacidiphilum fumariolicum. This bacterium was found to survive only if there are lanthanides present in the environment.[22] Compared to most other nondietary elements, non-radioactive lanthanides are classified as having low toxicity.[23]

See also

References

- ^ Krishnamurthy, Nagaiyar and Gupta, Chiranjib Kumar (2004) Extractive Metallurgy of Rare Earths, CRC Press, ISBN 0-415-33340-7

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ Greenwood, N. N. (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd Edition ed.). Oxford:Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 0-7506-3365-4.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Cullity, B. D. and Graham, C. D. (2011) Introduction to Magnetic Materials, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 9781118211496

- ^ أ ب ت ث Cotton, Simon (2006). Lanthanide and Actinide Chemistry. John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- ^ Sroor, Farid M.A.; Edelmann, Frank T. (2012). "Lanthanides: Tetravalent Inorganic". Encyclopedia of Inorganic and Bioinorganic Chemistry. doi:10.1002/9781119951438.eibc2033. ISBN 9781119951438.

- ^ Holleman, p. 1937.

- ^ dtv-Atlas zur Chemie 1981, Vol. 1, p. 220.

- ^ Bochkarev, Mikhail N.; Fedushkin, Igor L.; Fagin, Anatoly A.; Petrovskaya, Tatyana V.; Ziller, Joseph W.; Broomhall-Dillard, Randy N. R.; Evans, William J. (1997). "Synthesis and Structure of the First Molecular Thulium(II) Complex: [TmI2(MeOCH2CH2OMe)3]". Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 36 (12): 133–135. doi:10.1002/anie.199701331.

- ^ Winter, Mark. "Lanthanum ionisation energies". WebElements Ltd, UK. Retrieved 2 September 2010.

- ^ أ ب Fukai, Y. (2005). The Metal-Hydrogen System, Basic Bulk Properties, 2d edition. Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-00494-3.

- ^ Kohlmann, H.; Yvon, K. (2000). "The crystal structures of EuH2 and EuLiH3 by neutron powder diffraction". Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 299 (1–2): L16–L20. doi:10.1016/S0925-8388(99)00818-X.

- ^ Matsuoka, T.; Fujihisa, H.; Hirao, N.; Ohishi, Y.; Mitsui, T.; Masuda, R.; Seto, M.; Yoda, Y.; Shimizu, K.; Machida, A.; Aoki, K. (2011). "Structural and Valence Changes of Europium Hydride Induced by Application of High-Pressure H2". Physical Review Letters. 107 (2): 025501. Bibcode:2011PhRvL.107b5501M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.025501. PMID 21797616.

- ^ Tellefsen, M.; Kaldis, E.; Jilek, E. (1985). "The phase diagram of the Ce-H2 system and the CeH2-CeH3 solid solutions". Journal of the Less Common Metals. 110 (1–2): 107–117. doi:10.1016/0022-5088(85)90311-X.

- ^ Kumar, Pushpendra; Philip, Rosen; Mor, G. K.; Malhotra, L. K. (2002). "Influence of Palladium Overlayer on Switching Behaviour of Samarium Hydride Thin Films". Japanese Journal of Applied Physics. 41 (Part 1, No. 10): 6023–6027. Bibcode:2002JaJAP..41.6023K. doi:10.1143/JJAP.41.6023.

- ^ David A. Atwood, ed. (19 February 2013). The Rare Earth Elements: Fundamentals and Applications (eBook). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781118632635.

- ^ Wells, A. F. (1984). Structural Inorganic Chemistry (5th ed.). Oxford Science Publication. ISBN 978-0-19-855370-0.

- ^ Holleman, p. 1942

- ^ Perry, Dale L. (2011). Handbook of Inorganic Compounds, Second Edition. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-1-43981462-8. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- ^ Ryazanov, Mikhail; Kienle, Lorenz; Simon, Arndt; Mattausch, Hansjürgen (2006). "New Synthesis Route to and Physical Properties of Lanthanum Monoiodide†". Inorganic Chemistry. 45 (5): 2068–2074. doi:10.1021/ic051834r. PMID 16499368.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Palizban, A. A.; Sadeghi-aliabadi, H.; Abdollahpour, F. (1 January 2010). "Effect of cerium lanthanide on Hela and MCF-7 cancer cell growth in the presence of transferring". Research in Pharmaceutical Sciences. 5 (2): 119–125. PMC 3093623. PMID 21589800.

- ^ Yu, Lingfang; Xiong, Jieqi; Guo, Ling; Miao, Lifang; Liu, Sisun; Guo, Fei (2015). "The effects of lanthanum chloride on proliferation and apoptosis of cervical cancer cells: involvement of let-7a and miR-34a microRNAs". BioMetals. 28 (5): 879–890. doi:10.1007/s10534-015-9872-6. PMID 26209160. S2CID 15715889.

- ^ Pol, A., et al (2014). "Rare Earth Metals Are Essential for Methanotrophic Life in Volcanic Mudpots". Environ Microbiol. 16 (1): 255–264. doi:10.1111/1462-2920.12249. PMID 24034209.

- ^ McGill, Ian (2005) "Rare Earth Elements" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a22_607.

Cited sources

- Holleman, Arnold F.; Wiberg, Egon; Wiberg, Nils (2007). Lehrbuch der Anorganischen Chemie (in الألمانية) (102 ed.). Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-017770-1.

وصلات خارجية

- lanthanide Sparkle Model, used in the computational chemistry of lanthanide complexes

- USGS Rare Earths Statistics and Information

- Ana de Bettencourt-Dias: Chemistry of the lanthanides and lanthanide-containing materials

- Eric Scerri, 2007, The periodic table: Its story and its significance, Oxford University Press, New York, ISBN 9780195305739