اقتصاد إندونيسيا

جاكرتا، المركز المالي لإندونيسيا. | |

| العملة | الروپية (IDR, Rp) |

|---|---|

| 1 يناير – 31 ديسمبر | |

منظمات التجارة | APEC، WTO، G-20، IOR-ARC، RCEP، AFTA، ASEAN، EAS، ADB، أخرى |

| احصائيات | |

| السكان | ▲ 279,118,866 (June 2023)[1] |

| ن.م.إ | |

| ترتيب ن.م.إ | |

نمو ن.م.إ | |

ن.م.إ للفرد | |

ن.م.إ للفرد | |

| ▲ 2.57% (يناير 2024)[8] | |

السكان تحت خط الفقر | ▼ 2.5% في الفقر المدقع (تقديرات 2021)[9]

▼ 3.6% في الفقر متعدد الأبعاد (2022)[10] |

القوة العاملة | |

القوة العاملة حسب المهنة | |

| البطالة | ▼ 6.0% (تقديرات 2022)[2] |

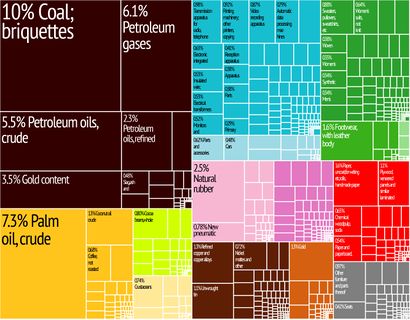

الصناعات الرئيسية | زيت النخيل، الأدوية، النفط، الفحم، الإلكترونيات، السيارات، الغاز الطبيعي، الصلب، الآلات، النقل، معالجة الأغذية، الطاقة الكهربائية، الاتصالات، صناعة الأخشاب، النسيج، الأحذية، السلع الاستهلاكية، الأجهزة الطبية، الأجهزة البصرية، الورق، الدوائر المتكاملة، الحرف اليدوية، الكيماويات، المأكولات البحرية، الخدمات المالية، الأدوية، السياحة |

| الخارجي | |

| الصادرات | ▲ 231.54 بليون دولار (2021)[17] |

السلع التصديرية | زيت النخيل، الصلب، المعادن، الآلات والمعدات الصناعية، الكيماويات، الغاز الطبيعي المسال، منتجات النسيج، الأحذية، السيارات، معدات النقل، منتجات الأخشاب، اللدائن |

شركاء التصدير الرئيسيين |

|

| الواردات | ▲ 237 بليون دولار (2022)[18] |

السلعة المستوردة | الآلات والمعدات الصناعية، الصلب، المواد الغذائية، منتجات النفط، الإلكترونيات، المواد الخام، المنتجات الكيميائية، معدات النقل |

شركاء الاستيراد الرئيسيين |

|

رصيد ا.أ.م | |

| ▲ +$3.46 بليون دولار (تقديرات 2021) | |

إجمالي الديون الخارجية | 423.1 بليون دولار (الربع الثالث، 2021)[19] |

| المالية العامة | |

| ▼ 37.0% من ن.م.إ. (الربع الثالث، 2021)[19] | |

| العوائد | 176.6 بليون دولار (تقديرات 2022)[20] |

| النفقات | 207.8 بليون دولار (تقديرات 2022)[7] |

| |

احتياطيات العملات الأجنبية | 146.4 بليون دولار (ديسمبر 2023)[26] |

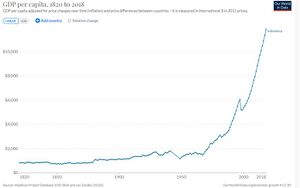

اقتصاد إندونيسيا هو اقتصاد مختلط موجـَّه،[27][28] وهو أحد اقتصادات الأسواق الناشئة في العالم وأكبر اقتصاد في جنوب شرق آسيا. وهي أيضاً عضو في مجموعة 20 وتصنف كبلد صناعي جديد.[29] وتحتل الترتيب 16 عالمياً من حيث ن.م.إ. الاسمي والترتيب السابع عالمياً من حيث ن.م.إ. (ق.ش.م.). إلا أن ن.م.إ. للفرد في إندونيسيا أقل من المتوسط العالمي. لا تزال إندونيسيا تعتمد على السوق المحلي وإنفاق الميزانية الحكومية وملكيتها للمؤسسات المملوكة للدولة (تمتلك الحكومة المركزية 141 مؤسسة). كما تلعب إدارة أسعار مجموعة من السلع الأساسية (بما في ذلك الأرز والكهرباء) دوراً هاماً في اقتصاد السوق الإندونيسي. إلا أنه منذ التسعينيات، أصبح معظم الاقتصاد تحت سيطرة الأفراد الإندونيسيين والشركات الأجنبية.[30][31][32]

في أعقاب الأزمة المالية الآسيوية 1997، استحوذت الحكومة على جزء كبير من أصول القطاع الخاص من خلال الاستحواذ على القروض البنكية المتعثرة وأصول المؤسسات من خلال عملية إعادة هيكلة الديون وبيعت الشركات المحجوزة للخصخصة بعد عدة سنوات. منذ 1999 تعافى الاقتصاد وتسارع النمو في السنوات الأخيرة إلى ما بين 4 إلى 6%.[33]

عام 2012، حلت إندونيسيا محل الهند كثاني أسرع اقتصاد نمواً ضمن مجموعة 20، بعد الصين. منذ ذلك الوقت، تباطأ معدل النمو السنوي ووصل الركود لمعدل 5%.[34] In 2012, Indonesia was the second fastest-growing G-20 economy, behind China, and the annual growth rate fluctuated around 5% in the following years.[35][36] Indonesia faced a recession in 2020 when the economic growth collapsed to −2.07% due to the COVID-19 pandemic, its worst economic performance since the 1997 crisis.[37]

In 2022, gross domestic product expanded by 5.31%, due to the removal of COVID-19 restrictions as well as record-high exports driven by stronger commodity prices.[38]

Indonesia is predicted to be the 4th largest economy in the world by 2045. Joko Widodo has stated that his cabinet's calculations showed that by 2045, Indonesia will have a population of 309 million people. By Widodo's estimate, there would be economic growth of 5−6% and GDP of US$9.1 trillion. Indonesia's income per capita is expected to reach US$29,000.[39]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

التاريخ

فترة سوكارنو

In the years immediately following the proclamation of Indonesian independence, both the Japanese occupation and the conflict between Dutch and Republican forces had crippled the country's production, with exports of commodities such as rubber and oil being reduced to 12 and 5% of their pre-WW2 levels, respectively.[40] The first Republican government-controlled bank, the Indonesian State Bank (Bank Negara Indonesia, BNI) was founded on 5 July 1946. It initially acted as the manufacturer and distributor of ORI (Oeang Republik Indonesia/Money of the Republic of Indonesia), a currency issued by the Republican Government which was the predecessor of Rupiah.[41] Despite this, currency issued during the Japanese occupation and by Dutch authorities was still in circulation, and the simplicity of the ORI made its counterfeiting relatively easy, worsening matters.[42] Between 1949 and 1960, Indonesia experienced several economic disruptions. The country's independence recognized by the Netherlands, the dissolution of the United States of Indonesia in 1950, the subsequent liberal democracy period, the nationalization of De Javasche Bank into the modern Bank Indonesia,[43] and the takeover of Dutch corporate assets following the West New Guinea dispute,[44] which all resulted in the devaluation of Dutch banknotes into half their value.[45]

During the guided democracy era in the 1960s, the economy deteriorated drastically as a result of political instability. The government was inexperienced in implementing macroeconomic policies, which resulted in severe poverty and hunger. By the time of Sukarno's downfall in the mid-1960s, the economy was in chaos with 1,000% annual inflation, shrinking export revenues, crumbling infrastructure, factories operating at minimal capacity, and negligible investment.[46] Nevertheless, Indonesia's post-1960 economic improvement was considered remarkable when taking into consideration how few indigenous Indonesians in the 1950s had received a formal education under Dutch colonial policies.[47]

فترة سوهارتو

عمدت الدولة منذ عام 1969 إلى وضع الخطط الخمسية المتتالية لتنمية الاقتصاد الوطني، وكان هدفها تطوير الصناعات الأساسية كالصلب والإسمنت والصناعات البتروكيمياوية والصناعات الخشبية، كما أن من أهدافها المهمة زيادة الإنتاج الزراعي وخاصة زراعة الأرز والمطاط الطبيعي. والغاية من ذلك رفع مستوى دخل الفرد وتوفير السكن والعلاج لأكبر عدد ممكن من السكان. وقد أقرَّت الدولة ست خطط خمسية امتدت ما بين عامي 1969 و1990 ونجحت في خفض معدلات التضخم، إذ تدنت من 60% عام 1960 إلى 8% في عام 1985 فارتفعت إلى 12.2% بين 1990 - 1998، وارتفع معدل التنمية السنوية من 1% عام 1979 إلى 6.1% في عام 1986 وبلغ 5.9% عام 1992 و5.8 بين 1990 – 1998 وكانت معدلات التنمية في هذه المرحلة كالتالي: الصناعة 5.9%، والزراعة 3.4%، والكهرباء 8.1%، والغاز 7.4%، والخدمات 5.6%، والتجارة 0.1.

ولذلك تطورت الاستثمارات المالية المحلية والأجنبية في البلاد فارتفعت من 2.86 مليار دولار أمريكي عام 1979 إلى 24.3 مليار دولار في سنة 1985، وزاد عدد اليد العاملة مليوناً ونصف مليون على ما كان عليه في الخطط الخمسية الأولى. كما أن الخطط المذكورة حملت إلى البلاد الاستقرار الاقتصادي النسبي رغم تقلبات سعر النفط والغاز، واستطاعت الدولة أن تجعل الميزان التجاري رابحاً، وتوضح ذلك الأرقام التالية بملايين الدولارات:

| الحصة من الناتج المحلي الإجمالي العالمي (ق.ش.م.)[48] | |

|---|---|

| السنة | الحصة |

| 1980 | 1.40% |

| 1990 | 1.89% |

| 2000 | 1.92% |

| 2010 | 2.24% |

| 2017 | 2.55% |

تستورد البلاد في الوقت نفسه الآلات والمكنات المختلفة والمواد الغذائية المتنوعة واللحوم والمشروبات. وتقدر قيمة واردات إندونيسية لعام 1998 بـ23.9 مليار دولار أمريكي وقيمة صادراتها بنحو 48.5 مليار دولار أمريكي. وناتجها الإجمالي بـ130600 مليون دولار ومع ذلك فإن الديون الخارجية تقدر بنحو 150.8 مليار دولار (1998). وقد تعرض الاقتصاد الإندونيسي وسوق المال في البلاد إلى هزة خطيرة خفضت قيمة الروبية الإندونيسية (1 دولار يساوي 8779 روبية) عام 1998.

الأزمة المالية الآسيوية

نتيجة للأزمة المالية والاقتصادية التي بدأت في منتصف 1997، تولت الحكومة ادارة كزء كبير من أصول القطاع الخاص عن طريق الاستحواذ على القروض البنكية الغير منتظمة وأصول المؤسسات عن طريق عمليات اعادة جدولة الديون.

ما بعد سوهارتو

منذ 2004، تعافى الاقتصاد الوطني، وشهد فترة أخرى من النمو الاقتصادي السريع.[49]

New Order

Following President Sukarno's downfall, the New Order administration brought a degree of discipline to economic policy that quickly brought inflation down, stabilized the currency, rescheduled foreign debt, and attracted foreign aid and investment. (See Inter-Governmental Group on Indonesia and Berkeley Mafia). Indonesia was until recently Southeast Asia's only member of OPEC, and the 1970s oil price rise provided an export revenue windfall that contributed to sustained high economic growth rates, averaging over 7% from 1968 to 1981.[50]

With high levels of regulation and dependence on declining oil prices, growth slowed to an average of 4.5% per annum between 1981 and 1988. A range of economic reforms was introduced in the late 1980s, including a managed devaluation of the rupiah to improve export competitiveness, and deregulation of the financial sector.[50] Foreign investment flowed into Indonesia, particularly into the rapidly developing export-oriented manufacturing sector, and from 1989 to 1997, the Indonesian economy grew by an average of over 7%.[50][51] GDP per capita grew 545% from 1970 to 1980 as a result of the sudden increase in oil export revenues from 1973 to 1979.[52] High levels of economic growth masked several structural weaknesses in the economy. It came at a high cost in terms of weak and corrupt governmental institutions, severe public indebtedness through mismanagement of the financial sector, rapid depletion of natural resources, and culture of favors and corruption in the business elite.[53]

Corruption particularly gained momentum in the 1990s, reaching to the highest levels of the political hierarchy as Suharto became the most corrupt leader according to Transparency International.[54][55] As a result, the legal system was weak, and there was no effective way to enforce contracts, collect debts, or sue for bankruptcy. Banking practices were very unsophisticated, with collateral-based lending the norm and widespread violation of prudential regulations, including limits on connected lending. Non-tariff barriers, rent-seeking by state-owned enterprises, domestic subsidies, barriers to domestic trade and export restrictions all created economic distortions.

The 1997 Asian financial crisis that began to affect Indonesia became an economic and political crisis. The initial response was to float the rupiah, raise key domestic interest rates, and tighten fiscal policy. In October 1997, Indonesia and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) reached an agreement on an economic reform program aimed at macroeconomic stabilization and the elimination of some of the country's most damaging economic policies, such as the National Car Program and the clove monopoly, both involving family members of Suharto. The rupiah remained weak, however, and Suharto was forced to resign in May 1998 after massive riots erupted. In August 1998, Indonesia and the IMF agreed on an Extended Fund Facility (EFF) under President B. J. Habibie that included significant structural reform targets. President Abdurrahman Wahid took office in October 1999, and Indonesia and the IMF signed another EFF in January 2000. The new program also has a range of economic, structural reform, and governance targets.

The effects of the crisis were severe. By November 1997, rapid currency depreciation had seen public debt reach US$60 billion, imposing severe strains on the government's budget.[56] In 1998, real GDP contracted by 13.1%, and the economy reached its low point in mid-1999 with 0.8% real GDP growth. Inflation reached 72% in 1998 but slowed to 2% in 1999. The rupiah, which had been in the RP 2,600/USD1 range at the start of August 1997 fell to 11,000/USD1 by January 1998, with spot rates around 15,000 for brief periods during the first half of 1998.[57] It returned to the 8,000/USD1 range at the end of 1998 and has generally traded in the Rp 8,000–10,000/USD1 range ever since, with fluctuations that are relatively predictable and gradual. However, the rupiah began devaluing past 11,000 in 2013, and as of November 2016 is around 13,000 Rp/USD1.[58]

Reform era

Since an inflation target was introduced in 2000, the GDP deflator and the CPI have grown at an average annual pace of 10¾% and 9%, respectively, similar to the pace recorded in the two decades prior to the 1997 crisis, but well below the pace in the 1960s and 1970s.[59] Inflation has also generally trended lower through the 2000s, with some of the fluctuations in inflation reflecting government policy initiatives such as the changes in fiscal subsidies in 2005 and 2008, which caused large temporary spikes in CPI growth.[60]

| Share of world GDP (PPP)[2] | |

|---|---|

| Year | Share |

| 1980 | 1.42% |

| 1990 | 1.93% |

| 2000 | 1.96% |

| 2010 | 2.29% |

| 2020 | 2.50% |

| 2021 | 2.44% |

In late 2004, Indonesia faced a 'mini-crisis' due to international oil prices rises and imports. The currency exchange rate reached Rp 12,000/USD1 before stabilizing. Under President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (SBY), the government was forced to cut its massive fuel subsidies, which were planned to cost $14 billion in October 2005.[61] This led to a more than doubling in the price of consumer fuels, resulting in double-digit inflation. The situation had stabilized but the economy continued to struggle with inflation at 17% in late 2005. Economic outlook became more positive as the 2000s progressed. Growth accelerated to 5.1% in 2004 and reached 5.6% in 2005. Real per capita income has reached fiscal levels in 1996–1997. Growth was driven primarily by domestic consumption, which accounts for roughly three-fourths of Indonesia's gross domestic product (GDP). The Jakarta Stock Exchange was the best performing market in Asia in 2004, up by 42%. Problems that continue to put a drag on growth include low foreign investment levels, bureaucratic red tape, and widespread corruption which costs RP. 51.4 trillion (US$5.6 billion) or approximately 1.4% of GDP annually.[بحاجة لمصدر] However, there is a robust economic optimism due to the conclusion of the peaceful 2004 elections.

As of February 2007, the unemployment rate was 9.75%.[62] Despite a slowing global economy, Indonesia's economic growth accelerated to a ten-year high of 6.3% in 2007. This growth rate was sufficient to reduce poverty from 17.8% to 16.6% based on the government's poverty line and reversed the recent trend towards jobless growth, with unemployment falling to 8.46% in February 2008.[63][64] Unlike many of its more export-dependent neighbors, Indonesia has managed to skirt the recession helped by strong domestic demand (which makes up about two-thirds of the economy) and a government fiscal stimulus package of about 1.4% of GDP. After India and China, Indonesia was the third-fastest growing economy in the G20. With the $512 billion economy expanded 4.4% in the first quarter from a year earlier and last month, the IMF revised its 2009 Indonesia forecast to 3–4% from 2.5%. Indonesia enjoyed stronger fundamentals with the authorities implemented wide-ranging economic and financial reforms, including a rapid reduction in public and external debt, strengthening of corporate and banking sector balance sheets and reducing bank vulnerabilities through higher capitalization and better supervision.[65]

In 2012, Indonesia's real GDP growth reached 6%, then it steadily decreased below 5% until 2015. After Joko Widodo succeeded SBY, the government took measures to ease regulations for foreign direct investments to stimulate the economy.[66] Indonesia managed to increase their GDP growth slightly above 5% in 2016–2017.[67] However, the government is currently still facing problems such as currency weakening, decreasing exports and stagnating consumer spending.[68][69] The current unemployment rate for 2019 is at 5.3%.[70]

Reform happened in Indonesia around the 1980s, when the Indonesian government states it will be attempting to economically integrate with global economies. They stated in 2017 that "Globalisation has made it difficult for the Indonesian economy to balance all other factors of the economy".[بحاجة لمصدر]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Data

The following table shows the main economic indicators in 1980–2022 (with IMF staff estimates in 2023–2028). Inflation under 5% is in green.[71]

| Year | GDP

(in Bil. US$PPP) |

GDP per capita

(in US$ PPP) |

GDP

(in Bil. US$nominal) |

GDP per capita

(in US$ nominal) |

GDP growth

(real) |

Inflation rate

(in Percent) |

Unemployment

(in Percent) |

Government debt

(in % of GDP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 189.7 | 1,286.3 | 99.3 | 673.2 | ▲9.9% | ▲18.0% | n/a | n/a |

| 1981 | ▲223.4 | ▲1,485.6 | ▲110.8 | ▲737.0 | ▲7.6% | ▲12.2% | n/a | n/a |

| 1982 | ▲242.6 | ▲1,581.6 | ▲113.8 | ▲741.9 | ▲2.2% | ▲9.5% | n/a | n/a |

| 1983 | ▲262.7 | ▲1,679.3 | ▲4.2% | ▲11.8% | n/a | n/a | ||

| 1984 | ▲292.7 | ▲1,835.4 | ▲107.2 | ▲672.2 | ▲7.6% | ▲10.5% | 1.6% | n/a |

| 1985 | ▲313.8 | ▲1,929.2 | ▲3.9% | ▲4.7% | ▲2.2% | n/a | ||

| 1986 | ▲343.1 | ▲2,068.7 | ▲7.2% | ▲5.8% | ▲2.8% | n/a | ||

| 1987 | ▲374.7 | ▲2,215.4 | ▲6.6% | ▲9.3% | ▼2.6% | n/a | ||

| 1988 | ▲415.0 | ▲2,406.0 | ▲107.3 | ▲621.9 | ▲7.0% | ▲8.1% | ▲2.9% | n/a |

| 1989 | ▲470.5 | ▲2,674.6 | ▲122.6 | ▲696.9 | ▲9.1% | ▲6.4% | n/a | |

| 1990 | ▲532.0 | ▲2,965.9 | ▲138.3 | ▲770.8 | ▲9.0% | ▲7.8% | ▼2.6% | n/a |

| 1991 | ▲599.1 | ▲3,285.4 | ▲154.6 | ▲847.6 | ▲8.9% | ▲9.4% | ▲2.7% | n/a |

| 1992 | ▲652.7 | ▲3,521.1 | ▲168.3 | ▲907.8 | ▲6.5% | ▲7.5% | ▲2.8% | n/a |

| 1993 | ▲721.4 | ▲3,827.8 | ▲190.9 | ▲1,013.1 | ▲8.0% | ▲9.7% | n/a | |

| 1994 | ▲792.3 | ▲4,135.8 | ▲213.7 | ▲1,115.6 | ▲7.5% | ▲8.5% | ▲4.5% | n/a |

| 1995 | ▲875.4 | ▲4,495.1 | ▲244.2 | ▲1,254.0 | ▲8.2% | ▲9.4% | ▲7.4% | n/a |

| 1996 | ▲961.2 | ▲4,878.9 | ▲274.7 | ▲1,394.5 | ▲7.8% | ▲8.0% | ▼5.0% | n/a |

| 1997 | ▲1,023.7 | ▲5,136.9 | ▲4.7% | ▲6.2% | ▼4.8% | n/a | ||

| 1998 | ▲58.4% | ▲5.5% | n/a | |||||

| 1999 | ▲919.2 | ▲4,507.9 | ▲169.2 | ▲829.6 | ▲0.8% | ▲20.5% | ▲6.4% | n/a |

| 2000 | ▲986.8 | ▲4,784.3 | ▲179.5 | ▲870.2 | ▲5.0% | ▲3.7% | ▼6.1% | 87.4% |

| 2001 | ▲1,045.8 | ▲4,999.0 | ▲3.6% | ▲11.5% | ▲8.1% | ▼73.7% | ||

| 2002 | ▲1,109.9 | ▲5,230.8 | ▲212.8 | ▲1,002.9 | ▲4.5% | ▲11.9% | ▲9.1% | ▼62.3% |

| 2003 | ▲1,185.9 | ▲5,510.4 | ▲255.4 | ▲1,186.8 | ▲4.8% | ▲6.8% | ▲9.7% | ▼55.6% |

| 2004 | ▲1,279.0 | ▲5,859.4 | ▲279.6 | ▲1,280.7 | ▲5.0% | ▲6.1% | ▲9.9% | ▼51.3% |

| 2005 | ▲1,394.2 | ▲6,297.4 | ▲310.8 | ▲1,403.9 | ▲5.7% | ▲10.5% | ▲11.2% | ▼42.6% |

| 2006 | ▲1,516.3 | ▲6,752.5 | ▲396.3 | ▲1,764.8 | ▲5.5% | ▲13.1% | ▼10.3% | ▼35.8% |

| 2007 | ▲1,656.1 | ▲7,271.3 | ▲470.1 | ▲2,064.2 | ▲6.3% | ▲6.3% | ▼9.1% | ▲38.1% |

| 2008 | ▲1,813.5 | ▲7,850.3 | ▲558.6 | ▲2,418.0 | ▲7.4% | ▲9.9% | ▼8.4% | ▼30.3% |

| 2009 | ▲1,910.9 | ▲8,155.8 | ▲577.5 | ▲2,465.0 | ▲4.7% | ▲4.8% | ▼7.9% | ▼26.5% |

| 2010 | ▲2,057.2 | ▲8,656.8 | ▲755.3 | ▲3,178.1 | ▲6.4% | ▲5.1% | ▼7.1% | ▼24.5% |

| 2011 | ▲2,229.5 | ▲9,213.2 | ▲892.6 | ▲3,688.5 | ▲6.2% | ▲5.3% | ▼6.6% | ▼23.1% |

| 2012 | ▲2,413.4 | ▲9,833.7 | ▲919.0 | ▲3,744.5 | ▲6.0% | ▲4.0% | ▼6.1% | ▼23.0% |

| 2013 | ▲2,535.0 | ▲10,188.3 | ▲5.6% | ▲6.4% | ▲6.3% | ▲24.9% | ||

| 2014 | ▲2,622.3 | ▲10,399.0 | ▲5.0% | ▲6.4% | ▼5.9% | ▼24.7% | ||

| 2015 | ▲2,647.7 | ▲4.9% | ▲6.4% | ▲6.2% | ▲27.0% | |||

| 2016 | ▲2,744.9 | ▲10,618.7 | ▲932.1 | ▲3,605.7 | ▲5.0% | ▲3.5% | ▼5.6% | ▲28.0% |

| 2017 | ▲2,894.1 | ▲11,073.5 | ▲1,015.5 | ▲3,885.5 | ▲5.1% | ▲3.8% | ▼5.5% | ▲29.4% |

| 2018 | ▲3,116.6 | ▲11,798.0 | ▲1,042.7 | ▲3,947.2 | ▲5.2% | ▲3.3% | ▼5.2% | ▲30.4% |

| 2019 | ▲3,331.6 | ▲12,481.9 | ▲1,119.5 | ▲4,194.1 | ▲5.0% | ▲2.8% | ▲30.6% | |

| 2020 | ▲2.0% | ▲7.1% | ▲36.1% | |||||

| 2021 | ▲3,582.4 | ▲13,158.6 | ▲1,187.7 | ▲4,362.7 | ▲3.7% | ▲1.6% | ▼6.5% | ▲37.9% |

| 2022 | ▲4,036.9 | ▲14,687.0 | ▲1,318.8 | ▲4,798.1 | ▲5.3% | ▲4.2% | ▼5.9% | ▼37.3% |

| 2023 | ▲4,393.4 | ▲15,835.8 | ▲1,417.4 | ▲5,108.9 | ▲5.0% | ▲3.6% | ▼5.3% | ▼36.4% |

| 2024 | ▲4,715.4 | ▲16,842.9 | ▲1,542.4 | ▲5,509.1 | ▲5.0% | ▲2.5% | ▼5.2% | ▼36.2% |

| 2025 | ▲5,049.2 | ▲17,876.1 | ▲1,670.6 | ▲5,914.7 | ▲5.0% | ▲2.5% | ▼5.1% | ▼36.0% |

| 2026 | ▲5,402.2 | ▲18,961.9 | ▲1,805.3 | ▲6,336.5 | ▲5.0% | ▲2.5% | ▼35.7% | |

| 2027 | ▲5,773.4 | ▲20,096.3 | ▲1,949.9 | ▲6,787.2 | ▲5.0% | ▲2.3% | ▼35.6% | |

| 2028 | ▲6,171.7 | ▲21,309.7 | ▲2,093.5 | ▲7,228.3 | ▲5.0% | ▲1.6% | ▼35.4% |

- Grey colors are estimations

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

التكوين

| القطاع | القطاعات الفرعية | ناتج 2006 (بالتريليون روپية) | النمو منذ 2003 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| الزراعة | المحاصيل الغذائية | 223 | 35 |

| محاصيل المزارع | 63 | 34 | |

| الماشية | 51 | 27 | |

| الغابات | 30 | 63 | |

| مصايد الأسماك | 73 | 60 | |

| التعدين | النفط والغاز | 188 | 97 |

| غير النفط والغاز | 131 | 145 | |

| المحاجر | 36 | 87 | |

| صناعة النفط والغاز | تكرير النفط | 120 | 139 |

| الغاز الطبيعي | 54 | 94 | |

| المحاجر | 213 | 35 | |

| صناعات أخرى | الأغذية، المشروبات، التبغ | 213 | 38 |

| المنسوجات، الأحذية، وغيرها | 91 | 34 | |

| الأخشاب، المنتجات الخشبية | 44 | 48 | |

| الورق، الطباعة | 40 | 43 | |

| الأسمدة، الكيماويات، المطاط | 96 | 68 | |

| الاسمنت، المحاجر الغير معدنية | 29 | 50 | |

| الحديد، الصلب، المعادن الأساسية | 20 | 52 | |

| معدات النقل، الآلات | 222 | 87 | |

| صناعات أخرى | 7 | 67 | |

| الكهرباء، الغاز، المياه | الكهرباء | 21 | 51 |

| Gas | 5 | 119 | |

| إمداد المياه | 4 | 43 | |

| الإنشاءات والبناء | الإنشاءات، البناء | 249 | 98 |

| التجارة، الفنادق والمطاعم | التجارة، التجزئة، الجملة | 387 | 48 |

| الفنادق | 17 | 52 | |

| المطاعم | 92 | 45 | |

| النقل | الطرق | 81 | 106 |

| البحري | 16 | 43 | |

| النهري، العبارات | 5 | 54 | |

| الجوي | 15 | 96 | |

| أخرى | 2 | 49 | |

| الاتصالات | الاتصالات | 88 | 123 |

| المالية، العقارات، الأعمال | الصرافة | 98 | 31 |

| مالية غير مصرفية | 27 | 87 | |

| خدمات متعلقة | 2 | 82 | |

| العقارات | 98 | 72 | |

| الخدمات | 47 | 71 | |

| خدمات القطاع العام | الحكومة، الدفاع | 104 | 63 |

| خدمات القطاع الخاص | الخدمات المدنية والمجتمعية | 60 | 92 |

| الترفيه | 10 | 46 | |

| الخدمات الفردية والشخصية | 100 | 69 |

المصدر: مكتب الإحصاءات الإندونيسي، بيانات الإنتاج السنوية.

القطاعات

الموارد الزراعية والحيوانية

لم تستغل الموارد الزراعية استغلالاً مرضياً بعد، وذلك لأن مساحات واسعة من الجزر تكاد تكون خالية من السكان، ولا ترى الزراعات الكثيفة والمتطورة إلا في جزيرتي جاوة ومادورة، وفي مناطق متفرقة من سومطرة وكليمنتان. وهذا يعني أن طاقات زراعية كبيرة لم تستثمر بعد. أما أهم الموارد فهي:

الغابات

تمتلك البلاد ثروة حقيقية من الغابات، وخاصة في جزر سومطرة وكليمنتان وسولاويسي وإيريان جاية. وفي البلاد أكثر من 3000 نوع من الأشجار. وتُعدّ الغابة بأخشابها المورد الثالث للدولة بعد النفط والغاز، فقد بلغت معدلات صادرات رقائق الخشب 3.604 مليون م3 بلغت قيمتها نحو 777.4 مليون دولار.

وصدر من الخشب المنشور 2.166 مليون م3 بقيمة 334.6 مليون دولار. وقد تعرضت غابات إندونيسية لحرائق مدمرة عامي 1997 - 1998 فتفاقمت الأزمة التي حاقت بالاقتصاد الإندونيسي وسوق المال فيها.

المطاط الطبيعي

أنتجت البلاد منه في عام 1986 نحو 1.075 مليون طن أي ما تعادل قيمته 708.2 مليون دولار ونحو 1.312.000 طن في عام 1994، وتكثر مزارع المطاط في جاوة وكليمنتان وسومطرة.

الأرز

أهم سلعة استهلاكية في البلاد، وقد تطور إنتاجه تطوراً كبيراً فارتفع من 12.2 مليون طن في عام 1969 إلى 36.537 مليون طن عام 1985، وقد وصل إنتاجه إلى 46.245.000 طن لعام 1994. ويسد هذا الرقم حاجة البلاد من الأرز، وتعمل الدولة على رفع الإنتاج إلى نحو 300 مليون طن عام 2000. ولا يصدر حتى اليوم إلا القليل من الأرز إلى الخارج.

الذرة

للذرة مكانة مهمة في الموارد الزراعية الإندونيسية لأنها غذاء جيد للإنسان والحيوان، وقد ارتفع إنتاجها من 2.292 مليون طن عام 1969 إلى 4.556 مليون طن في عام 1985 و6.617 مليون طن عام 1994. وتستهلك بأكملها تقريباً محلياً.

نبات المنيهوت (المانيوك)

ويعد زراعة أساسية في إندونيسية وإنتاجه كبير ويراوح بين 10.9 مليون طن عام 1969 و41 مليون طن عام 1995. ويستخرج من جذوره دقيق نشوي. وهنالك منتجات أخرى ثانوية ولكنها مهمة للبلاد مثل البن والشاي وقصب السكر وزيت النخيل وجوز الهند والفول السوداني وفول الصويا.

الموارد الحيوانية

أما الموارد الحيوانية فإن البلاد مفتقرة إليها نسبياً وتسعى الدولة لتنمية هذه الثروة لتسد حاجة البلاد منها، وتشير الإحصائيات إلى الأرقام التالية:

| الحيوانات | العدد بملايين الرؤوس |

|---|---|

| الماعز | 9.5 |

| الخنازير | 4.1 |

| الأغنام | 4.3 |

| الأسماك عامة | 2.375 مليون طن |

الثروات المعدنية

النفط

تحتل إندونيسية المركز الخامس عشر في إنتاج النفط عالمياً، ويزيد احتياطيها النفطي على 1.2 مليار طن ويتجمّع الاحتياطي الأساسي من النفط في الأرصفة القارية. ولقد اختلف إنتاج النفط بين عام وآخر، ولكن ازدياد الإنتاج هو السمة الأساسية في ذلك فقد أعطت آبار النفط في المدة بين 1970 و1983 نحو 957 مليون طن، وبلغ الإنتاج السنوي لعام 1998 نحو 76.5 مليون طن. ومكامن النفط كثيرة في البلاد، ولكن من أبرزها مكامن أواسط سومطرة ومكامن كليمنتان وإيريان. وتستهلك البلاد سنوياً ما يعادل 28ـ30 مليون طن، وتكرير هذه الكمية محلياً، وسعت الدولة لرفع طاقة التكرير إلى 53 مليون طن سنوياً في عام 1990. ويصدر أكثر من 80% من النفط المخصص للتصدير إلى دول شرقي آسيا وأسترالية والولايات المتحدة الأمريكية.

الغاز الطبيعي

تشغل إندونيسية المركز الخامس في إنتاج الغاز الطبيعي في آسيا ويبلغ احتياطيه ما يزيد على 1132 مليار متر مكعب، تجاور مكامنه مكامن النفط، وقد ارتفع إنتاجه من 7.9 مليار م3 في عام 1970 إلى 32 مليار م3 في عام 1986 و84.3 مليار م3 في عام 1998. وتستهلك البلاد أكثر من 11 مليار متر مكعب، ويصدر الباقي إلى السوق الدولية وخاصة إلى اليابان.

الفحم

يعتقد أن البلاد غنية جداً بالفحم وخاصة في جزيرة كليمنتان إذ تم اكتشاف مكامن مهمة يزيد احتياطيها على 680 مليون طن. وهناك مكامن غنية في سومطرة وسولاويسي. ويقدر الاحتياطي العام في البلاد بنحو 23213 مليون طن. أو ما يعادل 14.1% من احتياطي جنوبي آسيا وجنوبي شرقي آسيا. وبلغ الإنتاج المتوسط السنوي في المدة بين 1975 و1980 ما يقرب من 400 ألف طن وارتفع هذا الرقم في عام 1986 إلى 1.5 مليون طن، وإلى 58.6 مليون طن عام 1998 يصدر منها نحو 19 مليون طن.

الحديد

ما تزال الكميات المكتشفة من الحديد قليلة نسبياً في إندونيسية وتتمركز مكامنه في جاوة الوسطى والغربية. وقد ازداد الإنتاج من 914 ألف طن عام 1985 إلى نحو 1.373 مليون طن عام 1996، ولا يسد هذا الرقم حاجة البلاد من الحديد.

القصدير

وإندونيسية غنية جداً به وتملك أكبر احتياطي منه في آسيا وهو يعادل 1.5 مليون طن، وتُصنِّع منه البلاد سنوياً 30 - 32 ألف طن وتكاد الدولة تعده كله تقريباً ليُصَدر إلى الخارج.

البوكسيت

يصل احتياطي البوكسيت في إندونيسية إلى 700 مليون طن، وقد بلغ إنتاجه في سنة 1991 نحو 1406000 طن، صدر معظمه إلى الخارج.

النيكل

وتكثر مكامنه في مقاطعة سوركو وفي جزر الملوك وسولاويسي، ويصل الاحتياطي المكتشف إلى 4.9 مليون طن، وبلغ إنتاج النيكل الخام عام 1986 نحو 989600 طن والنيكل الحديدي 4801.2 طن، وصدر منهما في العام نفسه 916800 طن و4472.6 طن على التوالي.

النحاس

يعادل الاحتياطي العام من النحاس المكتشف 3 ملايين طن ومكامنه الأساسية في إيريان جاية، وبلغ إنتاجه 233.1 ألف طن في عام 1986 وارتفع إلى 292 ألف طن عام 1992 وإلى 309.7 ألف طن في عام 1993، يصدر 95% منه.

المنجنيز

البلاد غنية به ويقدر احتياطيه بثمانية ملايين طن، إلا أن إنتاجه لا يزيد على 20 ألف طن ويستثمر محلياً. وتمتلك البلاد ثروات باطنية مثل الرصاص والزنك والتيتان والفولفرام (التنغستين) والذهب والفضة، وقد بلغ إنتاج الذهب عام 1986 مايعادل 251كغ، والفضة 177كغ. وأنتجت البلاد ما يزيد على 100 ألف طن من الكاولين (الصلصال الأبيض) في سنة 1986 و681.435 ألف طن من المرو، وزاد إنتاج الإسمنت على 9.8 مليون طن في السنة نفسها وتعمل الدولة على رفع الإنتاج إلى 21 مليون طن.

صناعة السيارات

المالية، العقارات، الأعمال

النقل والمواصلات

النقل البري

تملك إندونيسية شبكة طرق جيدة يقدر طولها بنحو 203829كم وتقسم إلى:

- 12016 كم من الطرقات الواصلة والبعيدة المدى التي تصل بين المدن الرئيسية.

- 34287 كم من الطرقات المتوسطة الطول بين الأقاليم.

- 157526 كم من الطرقات القصيرة والثانوية في مختلف أنحاء البلاد.

- أما السكك الحديدية فطولها 8400كم منها 6400كم في جاوة وحدها.

النقل النهري

وللنقل النهري مكانة مرموقة في إندونيسية وخاصة في الجزر الكبيرة، وذلك لكثرة الغابات وغزارة الأمطار، ويُنقل نحو 25 مليون شخص نهرياً سنوياً، وينقل زهاء خمسة ملايين طن من البضائع ، أما النقل البحري فدوره مهم، وذلك بسبب كثرة الجزر والبحار الداخلية ويتم نقل 8.423.463 مليون طن من البضائع سنوياً وتقدر الحمولة بنسبة 27.6%.

النقل الجوي

للنقل الجوي أيضاً مكانة جيدة بسبب اتساع البلاد ويبلغ عدد الركاب 535717 راكباً سنوياً ويصل وزن البضائع المنقولة جواً إلى 35318 طناً. أما عدد الركاب في الرحلات الدولية فيبلغ نحو 1266344 راكباً في العام.

العلاقات الاقتصادية الخارجية

شرق آسيا

الولايات المتحدة

اتجاه الاقتصاد الكلي

| السنة | ن.م.إ. | مقابل الدولار (الروپية) |

معدل التضخم (%) | ن.م.إ. الاسمي للفرد (% من الولايات المتحدة) | ق.ش.م. الاسمية للفرد (% من الولايات المتحدة) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 60.143.191 | 627 | 18.0 | 5.25 | 5.93 |

| 1985 | 112.969.792 | 1.111 | 4.7 | 3.47 | 5.98 |

| 1990 | 233.013.290 | 1.843 | 7.8 | 3.01 | 6.63 |

| 1995 | 502.249.558 | 2.249 | 9.4 | 4.11 | 8.14 |

| 2000 | 1.389.769.700 | 8.396 | 3.8 | 2.32 | 6.92 |

| 2005 | 2.678.664.096 | 9.705 | 10.5 | 3.10 | 7.51 |

| 2010 | 6.422.918.230 | 8.555 | 5.1 | 6.38 | 9.05 |

| 2015 | 11.531.700.000 | 13.824 | 6.4 | 4.75 | 19.63 |

الاستثمارات

أكبر شركات عامة

Fortune Global 500

Indonesia has 1 company that rank in the Fortune Global 500 ranking for 2022.[72]

| World Rank | Company | Industry | Sales ($M) | Profits ($M) | Assets ($M) | Employees |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 223 | Pertamina | Oil and gas | 57,508 | 2,045 | 78,050 | 34,183 |

Forbes Global 2000

Indonesia has 7 companies that rank in the Forbes Global 2000 ranking for 2022.[73]

| World Rank | Company | Industry | Sales (billion $) |

Profits (billion $) |

Assets (billion $) |

Market Value (billion $) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 351 | Bank Rakyat Indonesia | Banking | 12.77 | 2.17 | 117.74 | 50.14 |

| 490 | Bank Mandiri | Banking | 9.53 | 1.96 | 121.09 | 26.88 |

| 518 | Bank Central Asia | Banking | 6.10 | 2.26 | 87.69 | 67.62 |

| 895 | Telkom Indonesia | Telecom | 10.02 | 1.73 | 19.45 | 31.88 |

| 1153 | Bank Negara Indonesia | Banking | 4.82 | 0.76 | 67.7 | 12.13 |

| 1749 | Bayan Resources | Mining | 2.85 | 1.21 | 2.43 | 9.82 |

| 1866 | Saratoga Investama Sedaya | Conglomerate/Investment | 0.12 | 1.74 | 4.29 | 3.38 |

الإنفاق العام

In 2015, total public spending was Rp 1,806 trillion (US$130.88 billion, 15.7% of GDP). Government revenues, including those from state-owned enterprises (BUMN), totaled Rp 1,508 trillion (US$109.28 billion, 13.1% of GDP) resulting in a deficit of 2.6%.[74] Since the 1997 crisis that caused an increase in debt and public subsidies and a decrease in development spending, Indonesia's public finances have undergone a major transformation. As a result of a series macroeconomic policies, including a low budget deficit, Indonesia is considered to have moved into a situation of financial resources sufficiency to address development needs. Decentralization, enacted during the Habibie administration, has changed the manner of government spending, which has resulted in around 40% of public funds being transferred to regional governments by 2006.

In 2005, rising international oil prices led to the government's decision of slashing fuel subsidies. It led to an extra US$10 billion for government spending on development,[75] and by 2006, there were an additional 5 billion due to steady growth, and declining debt service payments.[75] It was the country's first "fiscal space" since the revenue windfall during the 1970s oil boom. Due to decentralization and fiscal space, Indonesia has the potential to improve the quality of its public services. Such potential also enables the country to focus on further reforms, such as the provision of targeted infrastructure. Careful management of allocated funds has been described as Indonesia's main issue in public expenditure.[75][76]

In 2018, President Joko Widodo substantially increased the amount of debt by taking foreign loans. Indonesia has increased the debt by Rp 1,815 trillion compared to his predecessor, SBY. He has insisted that the loan is used for productive long-term projects such as building roads, bridges, and airports.[77] Finance Minister Sri Mulyani also stated that despite an increase of foreign loans and debt, the government has also increased the budget for infrastructure development, healthcare, education, and budget given to regencies and villages.[78] The government is insisting that foreign debt is still under control, and complying with relevant laws that limit debt to be under 60% of GDP.[79]

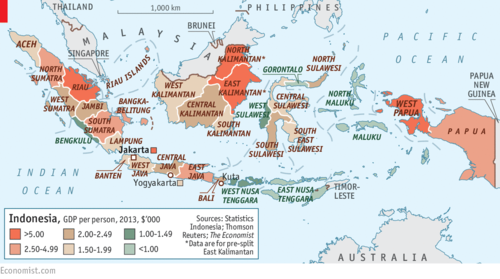

الأداء الإقليمي

Based on the regional administration implementation performance evaluation of 2009, by order, the best performance were:

- 3 provinces: North Sulawesi, South Sulawesi , and Central Java;

- 10 regencies: Jombang, Bojonegoro and Pacitan in East Java Province, Sragen in Central Java, Boalemo in Gorontalo, Enrekang in South Sulawesi, Buleleng in Bali, Luwu Utara in South Sulawesi, Karanganyar in Central Java, and Kulon Progo in Yogyakarta;

- 10 cities: Surakarta and Semarang in Central Java, Banjar in West Java, Yogyakarta city in Yogyakarta, Cimahi in West Java, Sawahlunto in West Sumatra, Probolinggo and Mojokerto in East Java, and Sukabumi and Bogor in West Java.[80]

Based on JBIC Fiscal Year 2010 survey (22nd Annual Survey Report) found that in 2009, Indonesia has the highest satisfaction level in net sales and profits for Japanese companies.[81]

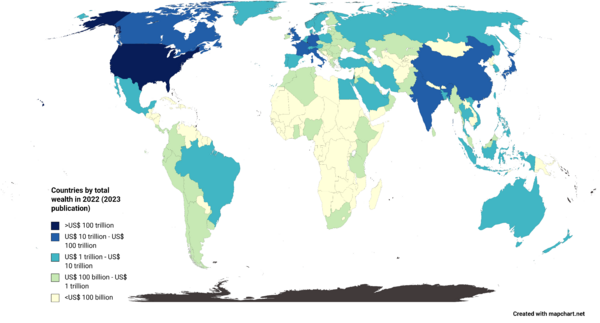

الثروة

National net wealth

National net wealth, also known as national net worth, is the total sum of the value of a nation's assets minus its liabilities. It refers to the total value of net wealth possessed by the citizens of a nation at a set point in time.[82] This figure is an important indicator of a nation's ability to take on debt and sustain spending and is influenced not only by real estate prices, equity market prices, exchange rates, liabilities and incidence in a country of the adult population but also by human resources, natural resources and capital and technological advancements, which may create new assets or render others worthless in the future. According to Credit Suisse, Indonesia has national net wealth of approximately $3.199 trillion, or about 0.765% of world net wealth, placing Indonesia at 17th, above Russia, Brazil, and Sweden.[83]

High-net-worth individuals

According to Asia Wealth Report, Indonesia has the highest growth rate of high-net-worth individuals (HNWI) predicted among the 10 largest Asian economies.[84] The 2015 Knight Frank Wealth Report reported that in 2014 there were 24 individuals with a net worth above US$1 billion. 18 of them lived in Jakarta while the others were spread among other large cities in Indonesia. 192 persons can be categorized as centamillionaires with over US$100 million of wealth and 650 persons as high-net-worth individuals whose wealth exceeded US$30 million.[85]

التحديات

Embezzlement and corrupt bureaucracy

Corruption is pervasive in the Indonesian government, affecting many fields that are central to barrier the country's economic development from local governments, the police, the private sector even various ministerial institutions which are close to the president.[86][87] It is related to problems of human capacities and technical resources remains a major challenge in merging effectiveness and integrity in public administration, especially in regencies and cities.[88] A 2018 World Economic Forum survey reports that corruption is the most problematic issue regarding doing business in Indonesia, as well as inefficient government bureaucracy policies. The survey also showed that 70% of entrepreneurs believe that corruption has grown in Indonesia, while low trust in the private sector is a major obstacle to foreign investment in the country.[89]

In 2019, a controversial bill regarding the anti-corruption body (Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK)) reduced the commission's effectiveness in tackling widespread corruption problems and stripped its independence was passed despite massive protests across the country.[90][91] There were 26 points in the revised law that crippled the commission and might further undermine efforts to eradicate corruption in Indonesia.[92]

Labour unrest

As of 2011, labour militancy was growing with a major strike at the Grasberg mine, the world's largest gold mine as well as the second-largest copper mine,[93] and numerous strikes elsewhere. A common issue was the attempts by foreign-owned enterprises to evade Indonesia's strict labour laws by calling their employees' contract workers. The New York Times expressed concern that Indonesia's cheap labor advantage might be lost. However, a large pool of the unemployed who will accept substandard wages and conditions remains available. One factor in the increase of militancy is increased awareness via the Internet of prevailing wages in other countries, and the generous profits foreign companies are making in Indonesia.[94]

On 1 September 2015, thousands of workers in Indonesia staged large demonstrations across the country in pursuit of higher wages and improved labour laws. Approximately 35,000 people rallied in total. They demanded a 22% to 25% increase in the minimum wage by 2016 and lower prices on essential goods, including fuel. The unions also want the government to ensure job security and ensure the fundamental rights of the workers.[95]

In 2020, thousands of workers across the country held a massive march to protest against the Omnibus Law on Job Creation that included several controversial rules, which revised minimum wages, lowered severance pay, relaxed firing rules, among other disadvantaging regulations for labors and factory workers.[96][97][98]

Inequality

Economic disparity and the flow of natural resource profits to Jakarta has led to discontent and contributed to separatist movements in areas such as Aceh and Papua. Geographically, the poorest fifth regions account for just 8% of consumption, while the wealthiest fifth account for 45%. While there are new laws on decentralization that may address the problem of uneven growth and satisfaction partially, there are many hindrances in putting this new policy into practice.[99] At a 2011 Makassar Indonesian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (Kadin) meeting, Disadvantaged Regions Minister said there are 184 regencies classified as disadvantaged areas, with around 120 in eastern Indonesia.[100] 1% of Indonesia's population has 49.3% of the country's $1.8 trillion wealth, down from 53.5%. However, it is ranked fourth after Russia (74.5%), India (58.4%) and Thailand (58%).[101]

Inflation

Inflation has long been a problem in Indonesia. Because of political turmoil, the country once suffered hyperinflation, with 1,000% annual inflation between 1964 and 1967,[102] resulting in severe poverty and hunger.[103] Even though the economy recovered quickly during the first decade of the New Order administration (1970–1981), never once was the inflation less than 10% annually. The inflation slowed during the mid-1980s; however, the economy was also languid due to the decrease in oil price that reduced its export revenue dramatically. The economy was again experiencing rapid growth between 1989 and 1997 due to the improving export-oriented manufacturing sector. Still, the inflation rate was higher than economic growth, and this caused a widening gap among Indonesians. Inflation peaked in 1998 during the 1997 crisis at over 58%, causing poverty to rise to the levels of the 1960s.[104] During the economic recovery and growth in recent years, the government has been trying to lower the inflation rate. However, it seems that inflation has been affected by global fluctuation and domestic market competition.[105] As of 2010, the inflation rate was approximately 7%, when its economic growth was 6%. To date, inflation is affecting the Indonesian lower middle class, especially those who are not able to afford food after price hikes.[106][107] At the end of 2017, Indonesia's inflation rate was 3.61%, or higher than the government-set forecast of 3.0–3.5%.[108]

انظر أيضاً

المصادر

- ^ "Indonesian Population June 2023". Ministry of Home Affairs (Indonesia). Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ^ أ ب ت ث "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ "WORLD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK 2022 OCT Countering the Cost-of-Living Crisis". www.imf.org. International Monetary Fund. p. 43. Retrieved October 11, 2022.

- ^ "Ekonomi Indonesia Tahun 2022 Tumbuh 5,31 Persen". BPS.go.id. Badan Pusat Statistik. 6 February 2023. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- ^ "Ekonomi Indonesia Triwulan II-2023 Tumbuh 5,17 Persen (y-on-y)". BPS.go.id. Badan Pusat Statistik. 7 August 2023. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةIMFWEODE - ^ أ ب ت ث "CIA World Factbook". CIA.gov. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- ^ "INDONESIA INFLATION JANUARY 2024". www.bps.go.id. Retrieved February 2, 2024.

- ^ "worldpoverty 2021". worldpoverty.

- ^ أ ب ت ث "Poverty and Inequality Platform". pip.worldbank.org. Retrieved 2022-05-17.

- ^ "Profil Kemiskinan di Indonesia Maret 2023". Badan Pusat Statistik. 17 July 2023. Retrieved 2023-07-29.

- ^ "Poverty and Inequality Platform". pip.worldbank.org. Retrieved 2023-09-26.

- ^ "Labor force, total - Indonesia". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ "Employment to population ratio, 15+, total (%) (national estimate) - Indonesia". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ "Indonesia : Distribution of employment by economic sector from 2010 to 2020". statista.com. Statista. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ^ "Ease of Doing Business in Indonesia". World Bank. Retrieved 2017-11-01.

- ^ أ ب "BPS Indonesia". www.bps.go.id/. Retrieved 17 Jan 2022.

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةBPS - ^ أ ب "Indonesia's External Debt Growth in Q3/2021 Remained Manageable". www.bi.go.id. Retrieved 2021-12-02.

- ^ "Realisasi Pendapatan Negara 2021". Retrieved 17 Jan 2022.

- ^ https://www.jcr.co.jp/download/6636ddac61f269abafa96cf04a6f048b1f8a634cf4e39f03ac/19i0083_BIndonesia_f_corrected_Feb42020.pdf[bare URL PDF]

- ^ "Indonesia | Japan Credit Rating Agency, LTD. - JCR".

- ^ "Indonesia | Japan Credit Rating Agency, LTD. - JCR".

- ^ أ ب "Indonesia Credit Rating". World Government Bonds (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 2020-05-19.

- ^ "Fitch Affirms Indonesia at 'BBB'; Outlook Stable". Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ^ "FOREIGN EXCHANGE RESERVES IN DECEMBER 2023". Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ^ Kim, Kyunghoon (2021). "Indonesia's Restrained State Capitalism: Development and Policy Challenges". Journal of Contemporary Asia. 51 (3): 419–446. doi:10.1080/00472336.2019.1675084.

- ^ https://journal.binus.ac.id/index.php/jas/article/view/9075

- ^ [1], g20.org. Retrieved 6 October 2009.

- ^ "Kemenperin – Ketika Swasta Mendominasi". Archived from the original on 2017-08-05.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "80 Persen Industri Indonesia Disebut Dikuasai Swasta". 3 March 2015.

- ^ "Kemenperin – Pengelola Kawasan Industri Didominasi Swasta". Archived from the original on 2017-08-05. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Acicis – Dspp". Acicis.murdoch.edu.au. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ^ "Acicis – Dspp". Acicis.murdoch.edu.au. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ^ "GDP growth (annual %)". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 2017-08-05.

- ^ "Why Indonesia's Apparent Stability Under Jokowi Is a Sign of Its Stagnation". worldpoliticsreview.com. Retrieved 2020-05-06.

- ^ "Pertumbuhan Ekonomi 2020 -2,07% Terburuk Sejak Krismon 98". CNBC Indonesia (in الإندونيسية). Retrieved 2021-02-05.

- ^ "Beating expectations, Indonesia's economy grows 5 percent in Q4". www.aljazeera.com (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2022-03-31.

- ^ "Indonesia Will be World's 4th Largest Economy by 2045, President Jokowi Says". Sekretariat Kabinet Republik Indonesia. 2017-03-27. Archived from the original on 27 June 2017. Retrieved 2021-05-25.

- ^ Lindblad, J. Thomas (2006). "Macroeconomic consequences of decolonization in Indonesia" (PDF). XIVth Conference of the International Economic History Association. Helsinki. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 August 2013. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- ^ "History – BNI". BNI. Archived from the original on 1 July 2018. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- ^ Hakiem, Lukman (9 August 2017). "Hatta-Sjafruddin: Kisah Perang Uang di Awal Kemerdekaan" (in الإندونيسية). Republika. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- ^ (2004). "From Java Bank to Bank Indonesia: A Case Study of Indonesianisasi in Practice".

Lindblad, J. Thomas (2004). "Van Javasche Bank naar Bank Indonesia. Voorbeeld uit de praktijk van indonesianisasi". Tijdschrift voor Sociale en Economische Geschiedenis (in الهولندية). 1: 28–46. - ^ van de Kerkhof, Jasper (March 2005). "Dutch enterprise in independent Indonesia: cooperation and confrontation, 1949–1958" (PDF). IIAS Newsletter. 36. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 August 2017. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- ^ "Period of Recognition of the Republic of Indonesia's Sovereignty up the Nationalization of DJB" (PDF). Special Unit for Bank Indonesia Museum: History Before Bank Indonesia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 October 2019. Retrieved 18 August 2017 – via Bank Indonesia.

- ^ "Sukarno's economic policy left me on the brink of ruin: Mochtar Riady's story (13)". Nikkei Asia (in الإنجليزية البريطانية). Retrieved 2023-03-19.

- ^ Baten, Jörg (2016). A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. p. 292. ISBN 9781107507180.

- ^ "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". www.imf.org-US. Retrieved 2018-09-19.

- ^ "Acicis – Dspp". Acicis.murdoch.edu.au. Retrieved 2011-08-29.

- ^ أ ب ت Schwarz (1994), pp. 52–7.

- ^ "Indonesia: Country Brief". Indonesia: Key Development Data & Statistics. The World Bank. September 2006.

- ^ "GDP info". Earthtrends.wri.org. Archived from the original on 20 February 2009. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ^ "Combating Corruption in Indonesia, World Bank 2003" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 January 2005. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ^ "Transparency International Global Corruption Report 2004". Transparency.org. Archived from the original on 2 September 2011. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ^ "Suharto tops corruption rankings". BBC News. 25 March 2004. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ^ Robison, Richard (17 November 2009). "A Slow Metamorphosis to Liberal Markets". Australian Financial Review.

- ^ "Historical Exchange Rates". OANDA. 16 April 2011. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ^ "XE: USD / IDR Currency Chart. US Dollar to Indonesian Rupiah Rates". xe.com. Retrieved 2020-05-06.

- ^ van der Eng, Pierre (4 February 2002). "Indonesia's growth experience in the 20th century: Evidence, queries, guesses" (PDF). Australian National University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 10 October 2017.

- ^ Temple, Jonathan (15 August 2001). "Growing into trouble: Indonesia after 1966" (PDF). University of Bristol. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 December 2016. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- ^ BBC News (31 August 2005). "Indonesia plans to slash fuel aid". BBC, London.

- ^ "Beberapa Indikator Penting Mengenai Indonesia" (PDF) (Press release) (in الإندونيسية). Indonesian Central Statistics Bureau. 2 December 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 April 2008. Retrieved 18 March 2008.

- ^ "Indonesia: Economic and Social update" (PDF) (Press release). World Bank. 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 2 April 2008.

- ^ "Indonesia: BPS-STATISTICS INDONESIA STRATEGIC DATA" (PDF) (Press release). BPS-Statistic Indonesia. 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 November 2010. Retrieved 5 November 2008.

- ^ "IMF Survey: Indonesia's Choice of Policy Mix Critical to Ongoing Growth". Imf.org. 28 July 2009. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ^ "Indonesian President Joko 'Jokowi' Widodo Two Years On". Time. Retrieved 2018-05-07.

- ^ "Jokowi Heads to 2018 With Backing of Stronger Indonesian Economy". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved 2018-05-07.

- ^ "Indonesian GDP Growth Disappoints, Adding to Currency Woes". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved 2018-05-07.

- ^ "Indonesian GDP growth falls short in 1Q, pressuring President Widodo". Nikkei Asian Review-GB. Retrieved 2018-05-07.

- ^ "World Economic Outlook (April 2020) - Unemployment rate". www.imf.org. Retrieved 2020-07-04.

- ^ "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects".

- ^ "Fortune Global 500 List 2022: See Who Made It". Fortune (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2023-01-13.

- ^ "The Global 2000 2022". Forbes (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2023-01-13.

- ^ Procee, Paul (5 May 2013). "Indonesia Economic Quarterly – January 2017" (PDF). World Bank. pp. 1–9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 February 2017. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- ^ أ ب ت "Spending for Development: Making the Most of Indonesia's New Opportunities Indonesia Public Expenditure Review 2007" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 August 2007. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ^ "The Politics of Free Public Services in Decentralized Indonesia" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 March 2012. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- ^ Ihsanuddin (2018-10-23). Maharani, Dian (ed.). "Jokowi: Utang Indonesia Kecil Dibanding Negara Lain". KOMPAS.com (in الإندونيسية). Jakarta: Kompas Cyber Media. Retrieved 2018-12-18.

- ^ Alika, Rizky (23 October 2018). "Sri Mulyani Jelaskan Manfaat Kenaikan Utang Rp 1.329 T di Era Jokowi - Katadata News". katadata.co.id. Retrieved 2018-12-18.

- ^ Belinda. "Utang Luar Negeri Indonesia Tetap Terkendali | Vibiznews" (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 2018-12-18.

- ^ "Govt names 23 regions with best performance". Waspada.co.id. 25 April 2011. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ^ "The power nature and Indonesia's economy". The Jakarta Post. 6 June 2011. Archived from the original on 27 August 2011. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ^ "National Statistics, Republic of China (Taiwan)". stat.gov.tw. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- ^ "Global wealth databook 2021" (PDF). Credit Suisse. June 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 June 2021.

- ^ "Close to 100,000 Super Rich Indonesians By 2015: Report". 2 September 2011. Archived from the original on 28 September 2012. Retrieved 2 September 2011.

- ^ Hilda B Alexander (19 March 2015). "18 Konglomerat Indonesia Tinggal di Jakarta".

- ^ Karmini, Niniek (6 December 2020). "Indonesia's social minister named suspect in million-dollar bribery case". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ Connors, Emma (25 November 2020). "Indonesian cabinet minister arrested in corruption probe". The Australian Financial Review. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ OECD (2016), Integrity Framework for Public Investment OECD Publishing

- ^ Most problematic factors for doing business in Indonesia, Archived 18 نوفمبر 2017 at the Wayback Machine, World Economic Forum

- ^ "Parliament ratifies controversial revisions to law governing Indonesia's Corruption Eradication Commission | Coconuts Jakarta". 17 September 2019.

- ^ "Suharto with a saw: Indonesia is lurching back into authoritarianism with Joko Widodo at the helm", (October 2020) The Economist

- ^ Corruption, Not KPK, the Main Obstacle to Investment in Indonesia, Antigraft Agency Says, September 25, 2019 Jakarta Globe

- ^ "Grasberg Open Pit, Indonesia". Mining Technology. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ^ Schonhardt, Sara (26 December 2011). "As Indonesia Grows, Discontent Sets in Among Workers". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2022-01-03. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- ^ Fatima, Kaniz (9 September 2015). "Textile workers protest for new minimum wage in Indonesia". BanglaApparel.com. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- ^ Afifa, Laila (2020-02-12). "Omnibus Is Throwing People and Democracy under the Bus". Tempo (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2020-11-21.

- ^ Bhwana, Petir Garda (2020-11-17). "Jokowi Asserts No Perpu to Revoke Job Creation Law". Tempo (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2020-11-21.

- ^ Hakim, Rakhmat Nur (16 November 2020). Erdianto, Kristian (ed.). "Jokowi Sebut Protes terhadap UU Cipta Kerja Akan Ditampung di PP dan Perpres". KOMPAS.com (in الإندونيسية). Jakarta: Kompas Cyber Media. Retrieved 2020-11-21.

- ^ "Indonesia Poverty and wealth, Information about Poverty and wealth in Indonesia". Nationsencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ^ "120 poor regencies are in the east". The Jakarta Post. 18 July 2011. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ^ "Indonesia's Richest One% Controls Nearly Half of Nation's Wealth: Report". Retrieved December 2, 2016.

- ^ By the time of Sukarno's downfall in the mid-1960s, the economy was in chaos with 1,000% annual inflation, shrinking export revenues, crumbling infrastructure, factories operating at minimal capacity, and negligible investment. Schwarz (1994), pages 52–57

- ^ "Ir Soekarno The First President of Indonesia". Welcome2indonesia.com. 18 May 2010. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ^ "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". Imf.org. 14 September 2006. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ^ "Indonesia – Financial & Private Sector Development in Indonesia". World Bank. 18 October 2007. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ^ "Faced With Skyrocketing Food Prices, Indonesian Govt to Speed Up Work on Food Estate". Jakarta Globe. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ^ "Indonesia Inflation Accelerates, Adding Pressure to Raise Rate :: Forex Trading Lebanon". Forextradinglb.com. 1 February 2011. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ^ "Indonesia's Dec annual inflation rate at 3.61 pct, above forecast". NASDAQ.com. 2018-01-01. Retrieved 2018-01-28.

قراءات إضافية

- Eng, Pierre van der (2010). "The sources of long-term economic growth in Indonesia, 1880–2008". Explorations in Economic History. 47 (3): 294–309. doi:10.1016/j.eeh.2009.08.004.

وصلات خارجية

- Indonesia Economic Aftershock from the Dean Peter Krogh Foreign Affairs Digital Archives

- BKPM – Indonesia Investment Coordinating Board And Indonesia Investment News

- Comprehensive current and historical economic data

- World Bank Summary Trade Statistics Indonesia

- Tariffs applied by Indonesia as provided by ITC's Market Access Map, an online database of customs tariffs and market requirements

- All articles with bare URLs for citations

- Articles with bare URLs for citations from March 2022

- Articles with PDF format bare URLs for citations

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- CS1 الإندونيسية-language sources (id)

- CS1 الهولندية-language sources (nl)

- CS1 الإنجليزية البريطانية-language sources (en-gb)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with unsourced statements from October 2018

- Articles with unsourced statements from September 2022

- اقتصاد إندونسيا

- أعضاء سابقون في الاوبك

- اقتصادات أعضاء منظمة التجارة العالمية