اللغة الأكادية

| الأكدية | |

|---|---|

| 𒀝𒅗𒁺𒌑 akkadû lišānum akkadītum | |

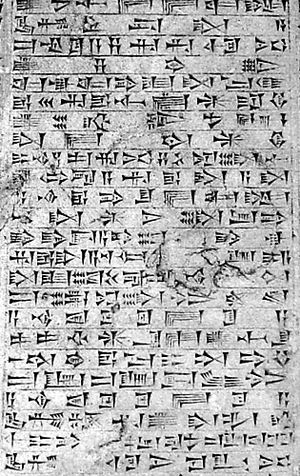

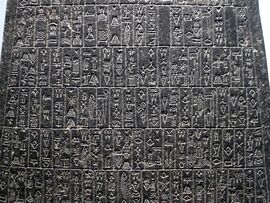

Akkadian language inscription on the obelisk of Manishtushu | |

| موطنها | بلاد آشور و بلاد بابل |

| المنطقة | بلاد الرافدين |

| منقرضة | 100 م |

| المسمارية السومرية-الأكدية | |

| الوضع الرسمي | |

لغة رسمية في | في البدء، أكد (وسط بلاد الرافدين)؛ lingua franca في الشرق الأوسط ومصر في آخر العصر البرونزي ومطلع العصر الحديدي. |

| أكواد اللغات | |

| ISO 639-2 | akk |

| ISO 639-2 | akk |

| ISO 639-3 | akk |

الأكّادية (لِشَانُم أَكّديتُمْ، 𒀝𒂵𒌈 أك.كا.دو) هي لغة سامية ظهرت في العراق منذ 3000 سنة قبل الميلاد. الأكادية هي لغة من اللغات السامية الشرقية. قبلها، كانت لغة العراق اللغة السومرية، وهي لغة غير سامية وغير مرتبطة (حسب معرفتنا الحاضرة) بأي لغة أخرى، وبعدها أصبحت لغة العراق الآرامية إلى حد (الفتح) الإسلامي الذي أدخل اللغة العربية إلى العراق وعرّب سكنة العراق.

كانت تدون بالخط المسماري فوق ألواح الطين التي يرجع تاريخها للنصف الأول للألفية الثالثة ق.م. قبل عام 2000 ق.م كانت لهجتان من الأكادية متداولة هناك هما البابلية في جنوب الرافدين والآشورية في شمالهما. وقد ظلتا سائدتين حتى ظهور المسيحية.

تنتمي اللغة الأكادية إلى عائلة لغوية معروفة وتشغل مكاناً مهماً بين لغات الأرض قديمها وحديثها، وهذه اللغات تضم عدة لغات تشترك في القواعد الأساسية وتراكيب لغوية ومفردات مشتركة، إن مهد هذه اللغات هو الجزيرة العربية لذلك نصطلح على تسميتها باللغات الجزرية.

إن الاسم الشائع لهذا اللغات هو اللغات السامية لانحدار متحدثها من سام بن نوح وفقاً لرواية العهد القديم( )، غير أن هذه التسمية اقترنت بفعل الحركات الصهيونية وعنصريتها بمصطلح سياسي استخدم لخدمة الأباطيل الصهيونية، لذلك فإن مصطلح (اللغات الجزرية) أقرب إلى العلمية( ).

واللغة الأكادية: هي أقرب اللغات الجزرية المعروفة وبالتالي أقربها إلى أصلها المشترك( )، وتمثل الأكادية ما اصطلح على تسميتها بالسامية الشرقية الشمالية، وهي لغة التفاهم في بلاد الرافدين، اشتق اسمها من اسم عاصمة الإمبراطور سرگون (2350-229 ق.م.)

يمكن أن تؤرخ الأكدية القديمة على وجه التقريب (2500-2000 ق.م.) وتنقسم إلى لهجتين: البابلية والآشورية.

- ابتدأ تدوينها بالخط المسماري قبل منتصف الألف الثالث قبل الميلاد.

- تفرعت في بداية الألف الثاني قبل الميلاد إلى لهجتين رئيسيتين ؛ هما البابلية في الجنوب والآشورية في الشمال.

- لم يتوقف استعمالها حتى القرن الأول الميلادي، أي إنها استمرت حية لمدة ثلاثة آلاف عام، وهذا ما يجعلها أطول لغات الأرض قديمها وحديثها عمرا.

Akkadian proper names were first attested in Sumerian texts from around the mid 3rd-millennium BC.[1] From about the 25th or 24th century BC, texts fully written in Akkadian begin to appear. By the 10th century BC, two variant forms of the language were in use in Assyria and Babylonia, known as Assyrian and Babylonian respectively. The bulk of preserved material is from this later period, corresponding to the Near Eastern Iron Age. In total, hundreds of thousands of texts and text fragments have been excavated, covering a vast textual tradition of mythological narrative, legal texts, scientific works, correspondence, political and military events, and many other examples.

Centuries after the fall of the Akkadian Empire, Akkadian (in its Assyrian and Babylonian varieties) was the native language of the Mesopotamian empires (Old Assyrian Empire, Babylonia, Middle Assyrian Empire) throughout the later Bronze Age, and became the lingua franca of much of the Ancient Near East by the time of the Bronze Age collapse c. 1150 BC. Its decline began in the Iron Age, during the Neo-Assyrian Empire, by about the 8th century BC (Tiglath-Pileser III), in favour of Old Aramaic. By the Hellenistic period, the language was largely confined to scholars and priests working in temples in Assyria and Babylonia. The last known Akkadian cuneiform document dates from the 1st century AD.[2] Mandaic and Suret are two (Northwest Semitic) Neo-Aramaic languages that retain some Akkadian vocabulary and grammatical features.[3]

Akkadian is a fusional language with grammatical case; and like all Semitic languages, Akkadian uses the system of consonantal roots. The Kültepe texts, which were written in Old Assyrian, include Hittite loanwords and names, which constitute the oldest record of any Indo-European language.[4][5]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

التبويب

(circa 2200 BC)

Akkadian belongs with the other Semitic languages in the Near Eastern branch of the Afroasiatic languages, a family native to the Middle East, Arabian Peninsula, the Horn of Africa, parts of Anatolia, North Africa, Malta, Canary Islands and parts of West Africa (Hausa). Akkadian and its successor Aramaic, however, are only ever attested in Mesopotamia and the Near East.

Within the Near Eastern Semitic languages, Akkadian forms an East Semitic subgroup (with Eblaite). This group distinguishes itself from the Northwest and South Semitic languages by its subject–object–verb word order, while the other Semitic languages usually have either a verb–subject–object or subject–verb–object order.

Additionally Akkadian is the only Semitic language to use the prepositions ina and ana (locative case, English in/on/with, and dative-locative case, for/to, respectively). Other Semitic languages like Arabic, Hebrew and Aramaic have the prepositions bi/bə and li/lə (locative and dative, respectively). The origin of the Akkadian spatial prepositions is unknown.

In contrast to most other Semitic languages, Akkadian has only one non-sibilant fricative: ḫ [x]. Akkadian lost both the glottal and pharyngeal fricatives, which are characteristic of the other Semitic languages. Until the Old Babylonian period, the Akkadian sibilants were exclusively affricated.[8]

التاريخ والكتابة

الكتابة

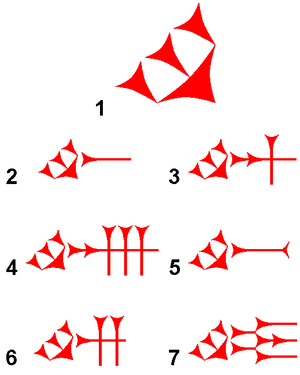

(1 = Logogram (LG) "mix"/syllabogram (SG) ḫi,

2 = LG "moat",

3 = SG aʾ,

4 = SG aḫ, eḫ, iḫ, uḫ,

5 = SG kam,

6 = SG im,

7 = SG bir)

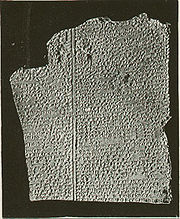

Old Akkadian is preserved on clay tablets dating back to c. 2500 BC. It was written using cuneiform, a script adopted from the Sumerians using wedge-shaped symbols pressed in wet clay. As employed by Akkadian scribes, the adapted cuneiform script could represent either (a) Sumerian logograms (i.e., picture-based characters representing entire words), (b) Sumerian syllables, (c) Akkadian syllables, or (d) phonetic complements. However, in Akkadian the script practically became a fully fledged syllabic script, and the original logographic nature of cuneiform became secondary, though logograms for frequent words such as 'god' and 'temple' continued to be used. For this reason, the sign AN can on the one hand be a logogram for the word ilum ('god') and on the other signify the god Anu or even the syllable -an-. Additionally, this sign was used as a determinative for divine names.

Another peculiarity of Akkadian cuneiform is that many signs do not have a well-defined phonetic value. Certain signs, such as AḪ, do not distinguish between the different vowel qualities. Nor is there any coordination in the other direction; the syllable -ša-, for example, is rendered by the sign ŠA, but also by the sign NĪĜ. Both of these are often used for the same syllable in the same text.

Cuneiform was in many ways unsuited to Akkadian: among its flaws was its inability to represent important phonemes in Semitic, including a glottal stop, pharyngeals, and emphatic consonants. In addition, cuneiform was a syllabary writing system—i.e., a consonant plus vowel comprised one writing unit—frequently inappropriate for a Semitic language made up of triconsonantal roots (i.e., three consonants plus any vowels).

تطورها

Akkadian is divided into several varieties based on geography and historical period:[9]

- Old Akkadian, 2500–1950 BC

- Old Babylonian and Old Assyrian, 1950–1530 BC

- Middle Babylonian and Middle Assyrian, 1530–1000 BC

- Neo-Babylonian and Neo-Assyrian, 1000–600 BC

- Late Babylonian, 600 BC–100 AD

One of the earliest known Akkadian inscriptions was found on a bowl at Ur, addressed to the very early pre-Sargonic king Meskiagnunna of Ur (c. 2485–2450 BC) by his queen Gan-saman, who is thought to have been from Akkad.[10] The Akkadian Empire, established by Sargon of Akkad, introduced the Akkadian language (the "language of Akkad") as a written language, adapting Sumerian cuneiform orthography for the purpose. During the Middle Bronze Age (Old Assyrian and Old Babylonian period), the language virtually displaced Sumerian, which is assumed to have been extinct as a living language by the 18th century BC.

Old Akkadian, which was used until the end of the 3rd millennium BC, differed from both Babylonian and Assyrian, and was displaced by these dialects. By the 21st century BC Babylonian and Assyrian, which were to become the primary dialects, were easily distinguishable. Old Babylonian, along with the closely related dialect Mariotic, is clearly more innovative than the Old Assyrian dialect and the more distantly related Eblaite language. For this reason, forms like lu-prus ('I will decide') were first encountered in Old Babylonian instead of the older la-prus. While generally more archaic, Assyrian developed certain innovations as well, such as the "Assyrian vowel harmony". Eblaite was even more so, retaining a productive dual and a relative pronoun declined in case, number and gender. Both of these had already disappeared in Old Akkadian. Over 20,000 cuneiform tablets in Old Assyrian have been recovered from the Kültepe site in Anatolia. Most of the archaeological evidence is typical of Anatolia rather than of Assyria, but the use both of cuneiform and the dialect is the best indication of Assyrian presence.[11]

Old Babylonian was the language of king Hammurabi and his code, which is one of the oldest collections of laws in the world. (see Code of Ur-Nammu.) The Middle Babylonian (or Assyrian) period started in the 16th century BC. The division is marked by the Kassite invasion of Babylonia around 1550 BC. The Kassites, who reigned for 300 years, gave up their own language in favor of Akkadian, but they had little influence on the language. At its apogee, Middle Babylonian was the written language of diplomacy of the entire Ancient Near East, including Egypt. During this period, a large number of loan words were included in the language from Northwest Semitic languages and Hurrian; however, the use of these words was confined to the fringes of the Akkadian-speaking territory.

Middle Assyrian served as a lingua franca in much of the Ancient Near East of the Late Bronze Age (Amarna Period). During the Neo-Assyrian Empire, Neo-Assyrian began to turn into a chancellery language, being marginalized by Old Aramaic. Under the Achaemenids, Aramaic continued to prosper, but Assyrian continued its decline. The language's final demise came about during the Hellenistic period when it was further marginalized by Koine Greek, even though Neo-Assyrian cuneiform remained in use in literary tradition well into Parthian times. The latest known text in cuneiform Babylonian is an astronomical almanac dated to 79/80 AD.[12] However, the latest cuneiform texts are almost entirely written in Sumerian logograms.[13]

Old Assyrian developed as well during the second millennium BC, but because it was a purely popular language — kings wrote in Babylonian — few long texts are preserved. From 1500 BC onwards, the language is termed Middle Assyrian.

During the first millennium BC, Akkadian progressively lost its status as a lingua franca. In the beginning, from around 1000 BC, Akkadian and Aramaic were of equal status, as can be seen in the number of copied texts: clay tablets were written in Akkadian, while scribes writing on papyrus and leather used Aramaic. From this period on, one speaks of Neo-Babylonian and Neo-Assyrian. Neo-Assyrian received an upswing in popularity in the 10th century BC when the Assyrian kingdom became a major power with the Neo-Assyrian Empire, but texts written 'exclusively' in Neo-Assyrian disappear within 10 years of Nineveh's destruction in 612 BC. The dominance of the Neo-Assyrian Empire under Tiglath-Pileser III over Aram-Damascus in the middle of the 8th century led to the establishment of Aramaic as a lingua franca[14] of the empire, rather than it being eclipsed by Akkadian.

After the end of the Mesopotamian kingdoms, which were conquered by the Persians, Akkadian (which existed solely in the form of Late Babylonian) disappeared as a popular language. However, the language was still used in its written form; and even after the Greek invasion under Alexander the Great in the 4th century BC, Akkadian was still a contender as a written language, but spoken Akkadian was likely extinct by this time, or at least rarely used. The last positively identified Akkadian text comes from the 1st century AD.[15]

فك رموزها

The Akkadian language began to be rediscovered when Carsten Niebuhr in 1767 was able to make extensive copies of cuneiform texts and published them in Denmark. The deciphering of the texts started immediately, and bilinguals, in particular Old Persian-Akkadian bilinguals, were of great help. Since the texts contained several royal names, isolated signs could be identified, and were presented in 1802 by Georg Friedrich Grotefend. By this time it was already evident that Akkadian was a Semitic language, and the final breakthrough in deciphering the language came from Edward Hincks, Henry Rawlinson and Jules Oppert in the middle of the 19th century.

اللهجات

The following table summarises the dialects of Akkadian certainly identified so far.

| اللهجة | المكان |

|---|---|

| الآشورية | شمال الرافدين |

| Babylonian | Central and Southern Mesopotamia |

| Mariotic | Central Euphrates (in and around the city of Mari) |

| Tell Beydar | Northern Syria (in and around Tell Beydar) |

Some researchers (such as W. Sommerfeld 2003) believe that the Old Akkadian variant used in the older texts is not an ancestor of the later Assyrian and Babylonian dialects, but rather a separate dialect that was replaced by these two dialects and which died out early.

Eblaite, formerly thought of as yet another Akkadian dialect, is now generally considered a separate East Semitic language.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

تغيرات صوتية

حركات الأكادية لا تختلف عن حركات العربية كثيرا. لكن تغيرت بعض حروفها من نطقها السامية الأصلية: ز أصبحت في العربية ذ، س أصبحت ث، ص أصبحت ظ و ض، ا أصبحت غ و ع و ح و ه، ش أصبحت س. ونون بسكون تغيب وتترك شدة على الحرف التالي. وتحفض النطق الأصلي للفاء (پ) وللسين والشين، التي كانت أصلا عكس نطقهم العربي الحاضر. فنجد مثلا (واكتب ـً بمعنى é الفرنسية في الأكادية):

- أٌزْنُمْ = أٌذْنٌ

- شُورُمْ = ثَوْرٌ

- صِلُّمْ = ضِلٌّ

- أًرْصًتُمْ = أَرْضٌ

- بًيلُمْ = بَعْلٌ

- اًدًيشُمْ = حَدِيثٌُ (أصل الكلمة الأكادية حَدَاثٌ)

- كَرْشُمْ = كَرْشٌ (أصلا ب س2)

- رًيشُمْ = رَأْسٌ

- شَرَّاقُمْ = سَرَّاقٌ

نحو

الاسم

كان إعراب الأكادية شبيه جدا بإعراب العربية، مثلا:

- بِيتُمْ = بَيْتٌ

- بِيتَمْ = بَيْتًا

- بِيتِمْ = بَيْتٍ

- بِيتَانْ = بَيْتَانِ

- بِيتِينْ = بَيْتَيْنِ

- بِيتُمْ = بَيْتٌ

- بِيتَاتُمْ = بُيُوتٌ

- بِيتَاتِمْ = بُيُوتٍ، بُيُوتًا

لكن في حال الإضافة يستعمل صيغة بلا إعراب:

- بِيتْ أَوِيلِمْ = بَيْتُ اَلْرًّجلِ

الضمير

الضمائر تختلف أكثر عن العربية:

- أَنَاكُ = أنا

- أَتَّ = أنتَ

- أَتِّ = أنتِ

- شُو = هو

- شِي = هي

- نِنُ = نحن

- أتُّنُ = أنتم

- أَتِّنَ = أنتن

- شُنُ = هم

- شِنَ = هن

الفعل

الفعل الأكادي يختلف كثيرا عن الفعل العربي، ففي الأكادي الفعل له صيغ كثير جدا. أهمها:

- الماضي (تشبه المضارع العربي)، مثلا إِرْفُدْ = جرى

- المضارع: إِرَفَّدْ = يجري

- الماضي البعيد: إِرْتَفَدْ = كان قد جرى

- الحال: رَفُدْ = هو جارٍ

الفعل التام في الأكادية:

تستخدم الأكادية الفعل التام، وليست الأكادية مختلفة عن أخواتها الجزيريات في هذا، كما يرى د. عامر سليمان في كتابه اللغة الأكدية، حيث يقول: " كان الاعتقاد حتى الثلاثينيات من هذا القرن أن للفعل في اللغة الأكادية، من حيث الزمن ما للفعل في اللغة العربية وغيرها من اللغات الجزيرية باستثناء ما يعرف بالحالة المستمرة، وإن ما يرد في النصوص الأكادية من صيغة فعلية دخل عليها المقطع (ـتَـ)، ما هي في الواقع إلا من الصيغ الثانوية التي تتفرع عن الصيغ الفعلية الأربعة الرئيسة التي تمت صياغتها بإدخال المقطع (تَـ)، أو (تن)، بعد الحرف الأول من الفعل، إلا أن بعض الباحثين في قواعد اللغة الأكادية وجدوا في بعض الصيغ الفعلية الأكادية التي تضم المقطع (تَـ) معان واستعمالات خاصة تختلف عن معاني واستخدامات صيغ الفعل في اللغات الجزرية الأخرى، وازداد البحث والتدقيق في النصوص الأكادية المختلفة للتعرف إلى هذه الصيغة الفعلية الجديدة وظهر كثير من الدراسات العلمية عنها، وإن كان هناك من الباحثين من أنكر وجودها أصلاً أو تغافل عنها أو عدها من الصيغ الثانوية، إلا أن معظم الباحثين في الوقت الحاضر يتفقون على وجود هذه الصيغة وقد تعارفوا على تسميتها بصيغة الفعل التام (perfect)، للتشابه الموجود بين معنى الفعل فيها مع معنى الفعل المعروف بهذا الاسم في اللغة الإنكليزية وغيرها من اللغات الأوربية". نراه يشبه الأكادية باللغات الأوربية في استعمال هذه الصيغة.

صياغة الفعل التام في الأكادية:

يصاغ الفعل التام بإدخال المقطع (ـتَـ) بعد الحرف الأول من الفعل مباشرة، وتتصل الضمائر الشخصية المتصلة نفسها الخاصة بالفعل الماضي والمضارع في أوله أو أوله وآخره لتكون صيغة الفعل التام ، ومع العلم بأن هذا الزمن يشترك (يتداخل مع) الأوزان التي تدخل فيها(a)t، فإنه يجب أن يُمَيَّز بوضوح منها، ومثل باقي الأزمنة، فإن التام يعبر عن مظهر فعلي(دلالة زمنية) في حين أن الأوزان المشتقة لها دلالة معجمية (معنوية).

استخدامات الفعل التام في الأكادية:

1- يستخدم في الأكادية للدلالة بالدرجة الأولى على حدث كان قد وقع وتم لتوه، مثال: Aštāpramkum> aštāprakkum بمعنى (لقد أرسلتها لتوي)

ونلحظ هنا بوضوح تشابه استعمالي العربية والأكادية لهذا الفعل. 2- يستخدم في الرسائل بعد ظرفي الزمان إننَّ، inanna (الآن)، وانمَّ anumma (من الآن وصاعداًَ) ليدل على أن وقت حدوث الفعل يصادف وقت الإرسال، مثال: Anumma ațţardakkum بمعنى: والآن أرسل إليك، فهو يعبِّر عن فعل أُنجِز الآن، ولكن أثره ما يزال ماثلاً، ,هذا كثير في الرسائل مع الأفعال الدالة على المتكلم المفرد، المصحوبة بظروف مثل (inanna) الآن، (anumma) " طيّه ضمنه، معه .." . ( anumma aštaprakkum) لقد كتبت إليك.. طيَّه .." ( inanna ațţardakkum ) الآن قد أرسلت إليك .." . أي أن الفعل التام هنا يدل على المضارع أكثر من دلالته على الماضي حيث إن عملية الإرسال لم تتم بعدها ولكنها في طريقها إلى ذلك . إذا كان هناك حدثان وقعا في الزمن الماضي فإن الحدث الأسبق زمناً يعبر عنه بالفعل الماضي البسيط، في حين يعبر عن الفعل الثاني الذي أعقبه في الحدوث بالفعل التام، مثال: Šumma awēlum … wardam … halqam ina sērim isbatma ana bēlišu inted-aššu *(intedi-am-šu) إذا قبض رجل على عبد .. هارب في الصحراء ثم جلبه إلى سيده وفي هذا المثال يشير الفعل التام إلى حدث تم في الماضي، في حين يشير الفعل الماضي البسيط إلى حدث وقع في الماضي البعيد أي قبل الحدث الذي عبر عنه الفعل التام . ويحصل ذلك في مثل هذا التتابع : ماض + (ma) + تام ويقال له (consecution temporum) نحو: (iqbiam ma ana bēlíja aštapram)، " قال هذا فكتبت إلى سيدي هذا، ويتخذ التام المجرد (G perfect)، الصيغ الآتية: The G perfect has the following forms: Sing. 3c. iptaras Plur. 3m iptarsū 2m. taptaras 3f.iptarsā 2f. taptarsī 2c. taptarsā 1c. aptaras 1c.niptaras

2- استخدم الفعل التام في العهد البابلي القديم للدلالة على الحدث الذي سيتم حدوثه قبل حدث آخر في المستقبل، وذلك في العبارات التابعة (غير الرئيسية) حيث يشير التام إلى المستقبل الذي يسبق مستقبل الجملة الرئيسية، وهذا ما يعرف بـ (futurum exactum) نحو:

(inūma gerrētum iptasā) عندما ستكون القوافل قد رحلت .

3- واتسع استخدام الفعل التام في العصور البابلية والآشورية المتأخرة، وغدا يستخدم للرواية عن الزمن الماضي في حين اقتصر استخدام الماضي البسيط للإخبار عن الحقائق فحسب. وقد تتلاقى العربية والأكادية في هذه النقطة، فصيغة (كان يفعل) في العربية تستعمل للتعبير عن استمرار الحدث في فترة من الزمن الماضي نحو: كان سيبويه يختلف إلى مجلس الخليل بن أحمد . 4- وتصريف الفعل التام يكون في الأكادية كتصريف الفعل الماضي البسيط في الحالات الثانوية ، والتام من كل وزن يتطابق مع الماضي التالي من الوزن، وعلى المرء أن يقرر ما إذا كانت الصيغة هي: تام مجرد (G perfect)، أو ماض preterite) Gt-)، وذلك اعتماداً على الشواهد المعجمية وعلى السياق، وعلى المثال (imtahsū)، فإذا وردت هذه الكلمة في التاريخ الحزبي وجب اعتبارها ماض بمعنى تقاتلوا، على ضوء الشاهد(mithusum)، (h =خ)في حين أن (htabalí) سوف تعتبر مجرداً تاماً بمعنى ظلم، لعدم وجود (hitbulum) .

5- وبالنسبة لإبدال التاء المقحمة (t of infix) أو مماثلتها لفاء الفعل نقول: إن التاء /t/ التي هي جزء من المقحمة الفعلية /ta/، سواء أكانت في الفعل التام أو الأوزان التائية t-stems أو الأوزان القانونية tn-stems، تبدل جزئياً الـ/g/ (أي مع الجهير).. كما تبدل كلياً مع الـ /d/ و/ț/ والحروف الصفيرية مع الـ/š/: (قد انتهوا) igdamrū === igtamrū (قد أرسلت)aţţardam=== aţtardam (قد أمسكت) assabat ===astabat (قد قال)izzakar ===iztakar 6- إن حركة عين الفعل(stem-vowel) التام مطابقة تماماً لمضارع المجرد، ، نحو: ssabat iptaqid, , irtapuol .ss تحتهما نقطتان 7- لاحظ أن حركة عين الفعل تحذف عندما تتصل بالفعل نهاية صوتية (iptaras-ū == iptarsū)

الحرف

بعض الحروف الأكادية تشبه حروف العربية، مثلا ؤُ=و، كِيمَ = كَـ. لاكن الكثير منهم تختلف، مثلا أَنَ = لِـ، إِنَ = في أي بِـ، إِشْتُ = من.

الجملة

في الأكادية، ترتيب الكلمات في الجملة عاديا الفاعل، ثم المفعول به، ثم الفعل، مثل الفارسية الحاظر. مثلا: شَرَّاقُمْ كَسْفَمْ أَنَ دَيَّانِم إِدِّنْ = أعطى السراق فضة للقاضي.

• لقد نتج عن اتخاذ الأكادية الخط المسماري في تدوينها إلى تغييرات عدة منها:

1- فقدان لأصوات الحلق.

2- فقدان التمييم المضاهي للتنوين في العربية.

3- إهمال حركات الإعراب المضاهية للعربية. وهي الضم والفتح والكسر.

4- تغيير ترتيب الجملة حيث يرد الفعل في الكدية آخر الجملة.

لهجات

- الأكادية القديمة (2334-2200 ق م)

- البابلية القديمة (2004-1595 ق م)

- البابلية الوسطى (1595-1000 ق م)

- البابلية المحدثة (1000-600 ق م)

- البابلية الفصيحة

- البابلية المؤخرة (600 ق م - 100 م)

- الآشورية القديمة (القرن 19 ق م)

- الآشورية الوسطى (1200-1000 ق م)

- الآشورية المحدثة (1000-600 ق م)

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

مواقع أخرى

Akkadian literature

- Atrahasis Epic (early 2nd millennium BCE)

- Enûma Elish (ca. 18th century BCE)

- Amarna letters (14th century BCE)

- Epic of Gilgamesh (Sin-liqe-unninni' "standard" version, 13th to 11th century BCE)

- Ludlul Bel Nemeqi

Notes

- ^ [1] Archived 2020-07-31 at the Wayback Machine Andrew George, "Babylonian and Assyrian: A History of Akkadian", In: Postgate, J. N., (ed.), Languages of Iraq, Ancient and Modern. London: British School of Archaeology in Iraq, pp. 37.

- ^ Geller, Markham Judah (1997). "The Last Wedge". Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie. 87 (1): 43–95. doi:10.1515/zava.1997.87.1.43. S2CID 161968187.

- ^ Müller-Kessler, Christa (July 20, 2009). "Mandaeans v. Mandaic Language". Encyclopædia Iranica (online 2012 ed.). Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und vorderasitische Archäologie 86 (1997): 43–95.

- ^ E. Bilgic and S. Bayram. Ankara Kultepe Tabletleri II. Turk Tarih Kurumu Basimevi, 1995. ISBN 975-16-0246-7

- ^ Watkins, Calvert. "Hittite". In: The Ancient Languages of Asia Minor. Edited by Roger D. Woodard. Cambridge University Press. 2008. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-511-39353-2

- ^ Krejci, Jaroslav (1990). Before the European Challenge: The Great Civilizations of Asia and the Middle East (in الإنجليزية). SUNY Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-7914-0168-2. Archived from the original on 2020-03-09. Retrieved 2020-02-26.

- ^ Mémoires. Mission archéologique en Iran. 1900. p. 53.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماة:0 - ^ Caplice, p.5 (1980)

- ^ Bertman, Stephen (2003). Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia. Oxford University Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-019-518364-1. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ^ K. R. Veenhof, Ankara Kultepe Tabletleri V, Turk Tarih Kurumu, 2010, ISBN 978-975-16-2235-8

- ^ Hunger, Hermann; de Jong, Teije (30 January 2014). "Almanac W22340a From Uruk: The Latest Datable Cuneiform Tablet". Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und vorderasiatische Archäologie. 104 (2). doi:10.1515/za-2014-0015. S2CID 163700758.

- ^ Walker, C. B. F. (1987). Cuneiform. Reading the Past (in الإنجليزية). Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-520-06115-6. Archived from the original on 2021-05-11. Retrieved 2020-10-15.

- ^ Bae, Chul-hyun (2004). "Aramaic as a Lingua Franca During the Persian Empire (538-333 B.C.E.)". Journal of Universal Language. 5: 1–20. doi:10.22425/jul.2004.5.1.1. Archived from the original on 2018-12-21. Retrieved 2018-12-20.

- ^ John Huehnergard & Christopher Woods, 2004 "Akkadian and Eblaite", The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the World's Ancient Languages, pg. 218.

الهامش

- Aro, Jussi (1957). Studien zur mittelbabylonischen Grammatik. Studia Orientalia 22. Helsinki: Societas Orientalis Fennica.

- Buccellati, Giorgio (1996). A Structural Grammar of Babylonian. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Buccellati, Giorgio (1997). "Akkadian," The Semitic Languages. Ed. Robert Hetzron. New York: Routledge. Pages 69–99.

- Bussmann, Hadumod (1996). Routledge Dictionary of Language and Linguistics. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-20319-8

- Caplice, Richard (1980). Introduction to Akkadian. Rome: Biblical Institute Press. (1983: ISBN 88-7653-440-7; 1988, 2002: ISBN 88-7653-566-7) (The 1980 edition is partly available online.)

- Dolgopolsky, Aron (1999). From Proto-Semitic to Hebrew. Milan: Centro Studi Camito-Semitici di Milano.

- Gelb, I.J. (1961). Old Akkadian Writing and Grammar. Second edition. Materials for the Assyrian Dictionary 2. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Huehnergard, John (2005). A Grammar of Akkadian (Second Edition). Eisenbrauns. ISBN 1-57506-922-9

- Marcus, David (1978). A Manual of Akkadian. University Press of America. ISBN 0-8191-0608-9

- Mercer, Samuel A B (1961). Introductory Assyrian Grammar. New York: F Ungar. ISBN 0-486-42815-X

- Sabatino Moscati (1980). An Introduction to Comparative Grammar of Semitic Languages Phonology and Morphology. Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 3-447-00689-7.

- Soden, Wolfram von (1952). Grundriss der akkadischen Grammatik. Analecta Orientalia 33. Roma: Pontificium Institutum Biblicum. (3rd ed., 1995: ISBN 88-7653-258-7)

- Woodard, Roger D. The Ancient Languages of Mesopotamia, Egypt and Aksum. Cambridge University Press 2008. ISBN 9780521684972

للاستزادة

General description and grammar

- Gelb, I. J. (1961). Old Akkadian writing and grammar. Materials for the Assyrian dictionary, no. 2. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226623041

- Huehnergard, J. A Grammar of Akkadian. Harvard Semitic Museum Studies 45. ISBN 978-1575069227

- Huehnergard, J. (2005). A Key to A Grammar of Akkadian . Harvard Semitic Studies. Eisenbrauns.

- Soden, Wolfram von: Grundriß der Akkadischen Grammatik. Analecta Orientalia. Bd 33. Rom 1995. ISBN 88-7653-258-7

- Streck, Michael P. Sprachen des Alten Orients. Wiss. Buchges., Darmstadt 2005. ISBN 3-534-17996-X

- Ungnad, Arthur: Grammatik des Akkadischen. Neubearbeitung durch L. Matouš, München 1969, 1979 (5. Aufl.). ISBN 3-406-02890-X

- Woodard, Roger D. The Ancient Languages of Mesopotamia, Egypt and Aksum. Cambridge University Press 2008. ISBN 9780521684972

الكتب المرجعية

- اللغة الأكادية (ريتشارد كابليتس)، ترجمة: عبد الرحمن دركزللي من منشورات جامعة حلب، كلية الآداب .

- المعجم المسماري، معجم اللغات الأكدية والسومرية والعربية، د. نائل حنون، بغداد، الطبعة الأولى2001.

- اللغات السامية تأليف كارل بروكلمان، ترجمة إلى العربية رمضان عبد التواب.

- اللغة الأكدية (البابلية الآشورية)، تأليف د. عامر سليمان، دار الكتب للطباعة والنشر، الموصل، 1991.

- معجم الكلمات الأكدية في اللغات الشرقية القديمة والإغريقية واللاتينية ، محمد داود سلوم، مكتبة لبنان ناشرون ، بيروت لبنان الطبعة الأولى 2003.

- Rykle Borger: Babylonisch-assyrische Lesestücke. Rom 1963.

- Part I: Elemente der Grammatik und der Schrift. Übungsbeispiele. Glossar.

- Part II: Die Texte in Umschrift.

- Part III: Kommentar. Die Texte in Keilschrift.

- Richard Caplice: Introduction to Akkadian. Biblical Institute Press, Rome 1988, 2002 (4.Aufl.). ISBN 88-7653-566-7

- Kaspar K. Riemschneider: Lehrbuch des Akkadischen. Enzyklopädie, Leipzig 1969, Langenscheidt Verl. Enzyklopädie, Leipzig 1992 (6. Aufl.). ISBN 3-324-00364-4

Dictionaries

- Jeremy G. Black, Andrew George, Nicholas Postgate: A Concise Dictionary of Akkadian. Harrassowitz-Verlag, Wiesbaden 2000. ISBN 3-447-04264-8

- Wolfram von Soden: Akkadisches Handwörterbuch. 3 Bde. Wiesbaden 1958-1981. ISBN 3-447-02187-X

Akkadian Cuneiform

- Cherry, A. (2003). A basic neo-Assyrian cuneiform syllabary. Toronto, Ont: Ashur Cherry, York University.

- Cherry, A. (2003). Basic individual logograms (Akkadian). Toronto, Ont: Ashur Cherry, York University.

- Rykle Borger: Mesopotamisches Zeichenlexikon. Alter Orient und Altes Testament (AOAT). Bd 305. Ugarit-Verlag, Münster 2004. ISBN 3-927120-82-0

- René Labat: Manuel d'Épigraphie Akkadienne. Paul Geuthner, Paris 1976, 1995 (6.Aufl.). ISBN 2-7053-3583-8

Technical literature on specific subjects

- Ignace J. Gelb: Old Akkadian Writing and Grammar. Materials for the Assyrian dictionary. Bd 2. University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1952, 1961, 1973. ISBN 0-226-62304-1 ISSN 0076-518X

- Markus Hilgert: Akkadisch in der Ur III-Zeit. Rhema-Verlag, Münster 2002. ISBN 3-930454-32-7

- Walter Sommerfeld: Bemerkungen zur Dialektgliederung Altakkadisch, Assyrisch und Babylonisch. In: Alter Orient und Altes Testament (AOAT). Ugarit-Verlag, Münster 274.2003. ISSN 0931-4296

وصلات خارجية

- Akkadian cuneiform on Omniglot (Writing Systems and Languages of the World)

- Akkadian Language Samples

- A detailed introduction to Akkadian

- Sample pages of Introductory Assyrian Grammar by Samuel A B Mercer

- Akkadian-English-French Online Dictionary

- Old Babylonian Text Corpus (includes dictionary)

- The Assyrian Dictionary of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago (CAD)

- Old Akkadian Writing and Grammar, by I. J. Gelb (1952)

- Glossary of Old Akkadian, by I. J. Gelb (1957)

- Recordings of Assyriologists Reading Babylonian and Assyrian

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Missing redirects

- Articles containing Akkadian-language text

- Languages with ISO 639-2 code

- Language articles with unreferenced extinction date

- Language articles missing Glottolog code

- Language articles with unsupported infobox fields

- Pages using multiple image with auto scaled images

- Pages using multiple image with manual scaled images

- Akkadian language

- الهلال الخصيب

- لغات سامية شرقية

- لغات قديمة